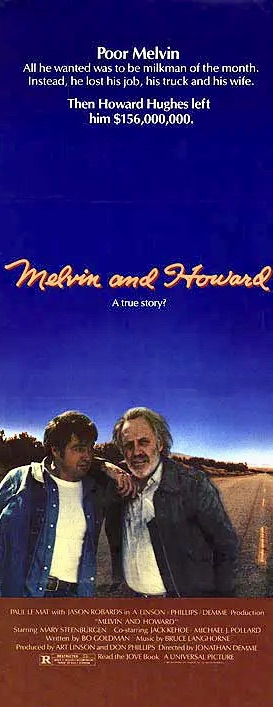

Over the years there have been numerous biographies written about aviation legend/studio mogul/eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes; everything from fake ones like Clifford Irving’s Autobiography of Howard Hughes to definitive accounts such as Howard Hughes: His Life and Madness by Donald L. Bartlett and James B. Steele. In contrast, there have been very few motion pictures about him. Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator (2004), based on the Bartlett & Steele biography, is the only feature film about his life to date. There was also a TV movie, The Amazing Howard Hughes (1977), with Tommy Lee Jones in the title role, and Jonathan Demme’s Melvin and Howard (1980), a quirky docudrama/comedy about Melvin E. Drummar (Paul Le Mat), a Utah man who claimed Hughes (Jason Robards Jr.) named him in his will after rescuing him in the Nevada desert.

Strangely enough, my favorite film about Howard Hughes isn’t a biopic at all but a noir-like melodrama featuring a character who was clearly inspired by the megalomaniac tycoon – Caught (1949), by German director Max Ophuls. Smith Ohlrig, the business tycoon modeled on Hughes, may not resemble him in terms of a biographical profile but on a psychological level he is the epitome of Hughes in the way he interacted with women, his employees and industry rivals.

Continue reading