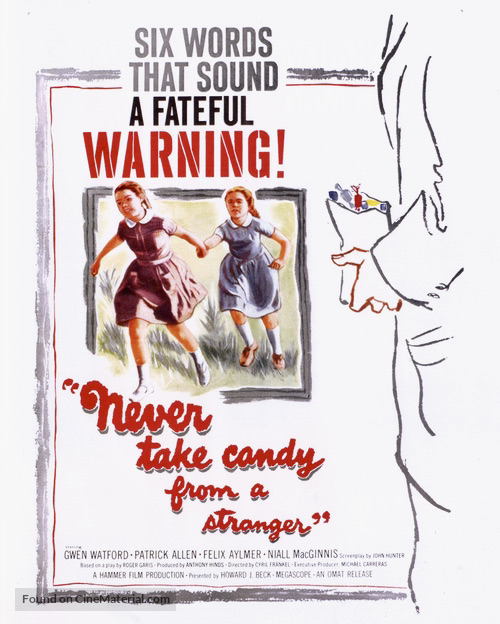

Hammer Studios, home to vampires, werewolves, mummies, Quatermass Xperiments, pirates….and child molesters? In 1960, the British film production company (originally founded in 1934), ventured into decidedly new territory from their usual formulaic mix of horror films, suspense thrillers and costume adventures. Never Take Candy from a Stranger (known as Never Take Sweets from a Stranger in the the U.K.) was Hammer’s attempt at a serious adult drama that addressed a controversial topic most major studios wouldn’t touch at that time.

Continue readingMonthly Archives: July 2021

Fritz Lang’s Two-Part Indian Epic

The film industry is rife with tales about directors who struggled and failed to bring their dream projects to the screen and the subject would make a fascinating, behind-the-scenes non-fiction book about the precarious nature of moviemaking. Among the more famous examples are Orson Welles, who pitched a film version of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to RKO executives, who instead chose Welles’ second idea, Citizen Kane, Josef von Sternberg’s ambitious 1937 production of I, Claudius, which was started but never completed due to disagreements between the director and Charles Laughton plus the injury of leading lady Merle Oberon in a car accident, and Robert Altman, who wanted to make a film version of the 1997 documentary Hands on a Hard Body and had even cast it but died before production could begin. Yet, for all the films-that-might-have-been, there are many examples of directors who finally succeeded in making their passion projects and one of them is Fritz Lang. His lifelong desire to make a film of the 1917 novel, The Indian Tomb, written by his former wife Thea Von Harbou, was finally realized in the late 1950s when he started production on a lavish movie adaptation that would be released in two parts as The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb, both 1959.

Continue readingMister Total Irreverence

Among most Fields’ enthusiasts, The Bank Dick is considered one of his best films, right up there with It’s a Gift (1934). It’s also the only film in which Fields enjoyed full creative control and it would be his last. His final starring role in Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941) was an unhappy experience and turned into one long battle with the Universal top brass over scripting and censorship issues.

Continue readingFrench Twists

Marina (Romy Schneider) and Claude (Gabriele Tinti) have a violent argument after leaving an inn in the French countryside. A pistol is fired, Claude roughs up his girlfriend and the couple speed off in a convertible. The car leaves the main road and races along the cliffs of the Brittany coastline until it plunges over a ledge into the sea below with Claude at the wheel. Among the hillside rocks, we see Marina, who miraculously escaped from the car and is the only witness at the scene. All of this unfolds under the opening credits of Qui? (1970), a rarely seen French film which offers some odd twists and turns in its brisk 73-minute running time (In some regions it was released under the title The Sensuous Assassin, which is completely misleading in regards to the actual storyline).

Continue readingThose Men and Women in White

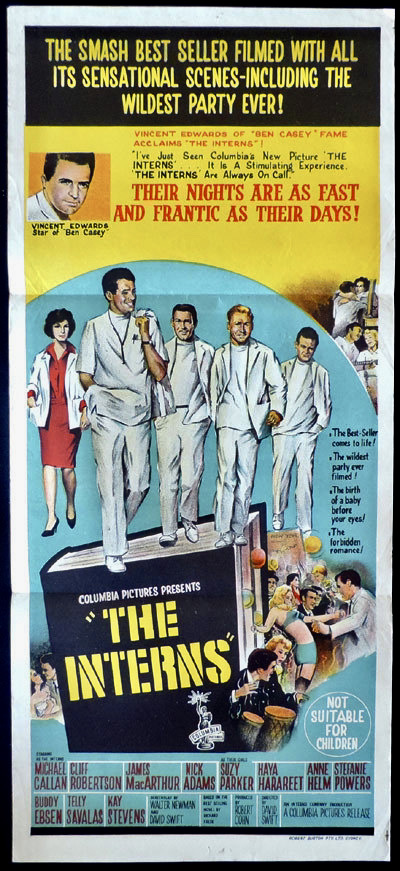

What could be a more ideal setting than a hospital to explore countless dramatic scenarios, character relationships and potentially hot-button topical issues that affect both the public and the medical community? With each decade new variations on the medical drama formula emerge and one of the most successful films in this genre in the early sixties was The Interns (1962).

Continue readingHe Blowed Up Real Good!

Remember Big Jim McBob (Joe Flaherty) and Billy Sol Hurok (John Candy) as the hayseed hosts of “Farm Report” on the legendary SCTV comedy series? These farmer-turned-film-reviewers loved movies where people and things blew up and eventually their hog report turned into a talk show where they blew up famous celebrities every week like Meryl Streep, The Village People, Brooke Shields, singer Neil Sedaka or Dustin Hoffman as Tootsie. Well, these guys would love Rod Steiger in Hennessy (1975) because he blows up real good!

Continue readingThrough the Eyes of a Child

Roberto Rossellini’s Roma, Citta Aperta (Rome, Open City, 1945) is generally acknowledged as the film that ushered in the neorealism movement and set the tone and style for the postwar Italian films that followed. But the roots of neorealism can be traced back to Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione (1943) and Vittorio De Sica’s The Children Are Watching Us (1944, I bambini ci guardano), both of which were filmed in 1942 but encountered distribution problems upon their release in the fall of 1942 when the war finally came to Italy and the bombings began. Ossessione was also the victim of Fascist censorship which reduced the film to less than half of its original running time and for years it was denied distribution in the U.S. due to an infringement of copyright (it was an uncredited adaptation of the James M. Cain novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice). The Children Are Watching Us didn’t fare any better during its limited release and for years it was a difficult film to see in its original form, even in its own country.

Continue readingJeanne Moreau is Mata Hari

The road to international fame was a long and arduous journey for Jeanne Moreau but it all began in 1948 when she became a stage actress at age 18. She started appearing in films a year later though it wasn’t until 1958 that she emerged as an important French actress, thanks to two Louis Malle features, the noir thriller Elevator to the Gallows and the scandalous romantic drama, The Lovers. More famous career-defining roles followed such as Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte (1961), Francois Truffaut’s Jules and Jim (1962), Jacques Demy’s Bay of Angels (1963) and Luis Bunuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid (1964). Yet, in terms of global recognition, she probably reached her peak in the mid-sixties when she appeared in big-budget Hollywood productions like The Victors (1963), The Train (1964) and The Yellow Rolls-Royce (1964). It was during this period that she appeared in Mata Hari, Agent H21 aka Secret Agent FX18 (1964), one of her least known and rarely seen movies.

Continue readingTurn On, Tune In, Drop Out

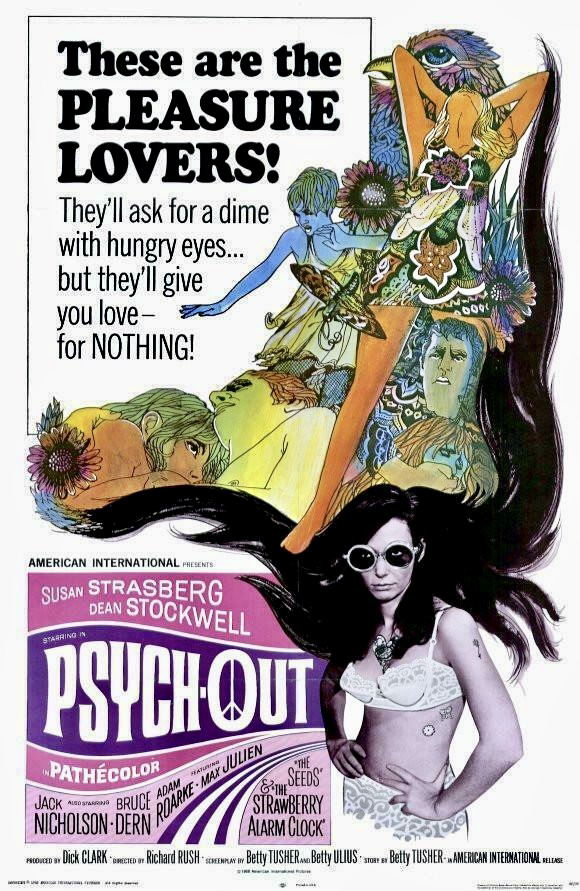

The Hippie movement of the mid-sixties, which first flourished in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, has rarely been captured accurately in Hollywood feature films but there have been a few exceptions and one of the most notable is Psych-Out (1968). Filmed on location in San Francisco by cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs, under the director of Richard Rush (The Stunt Man, 1980), the American-International release captures a moment in time as well as any documentary on the same subject. On a visual level, you couldn’t ask for a better snapshot of the period from the clothes to the hair styles to the social behavior and counterculture attitude. Even the now dated hipster jargon, some of which will make you cringe, seems true to the period. If only the musical acts featured had been less a top forty fabrication than the real thing (Only The Seeds have any credibility among the groups on display), Psych-Out might have had a more significant impact upon its release.

Continue reading