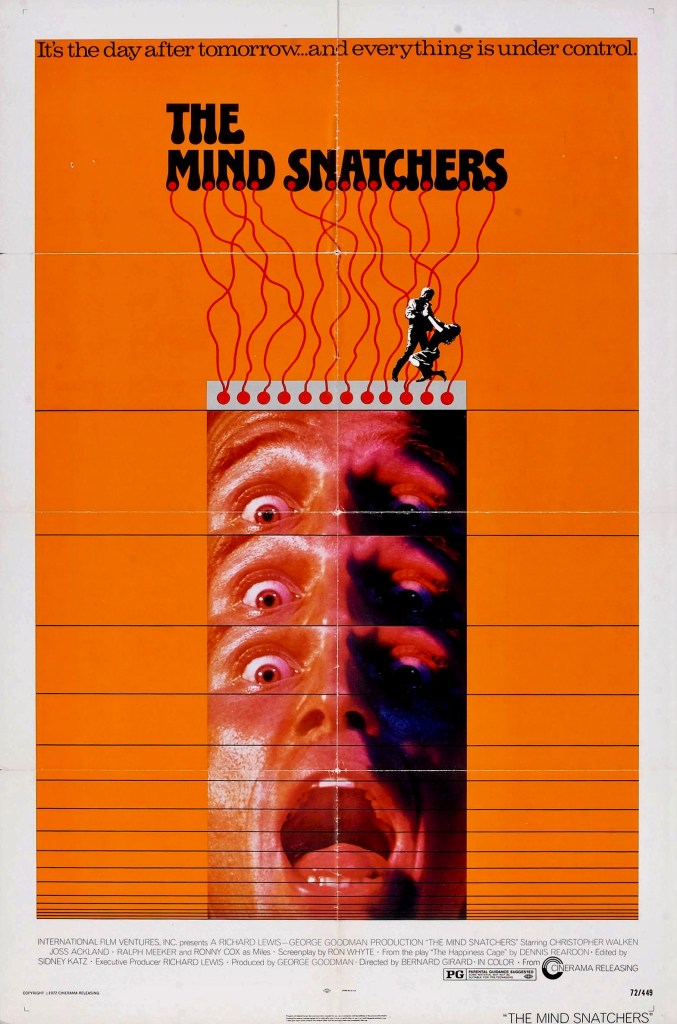

Think back to when you first saw Christopher Walken and Ronnie Cox in a feature film. Did you know the two actors co-starred in a low-budget production in 1972 called The Mind Snatchers in the early phase of their careers? 1976 was the year when Walken first captured my attention in two small supporting roles; the first being Paul Mazursky’s semi-autographical drama Next Stop, Greenwich Village, where he played an aspiring actor. In the second film, a supernatural horror thriller called The Sentinel, he played a cop. He followed these with an even more memorable supporting role in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977) as the strangely morbid brother of the title character. Ronnie Cox, on the other hand, made a haunting and unforgettable impression as the doomed Drew in Deliverance (1972), John Boorman’s critically acclaimed adaptation of the James Dickey novel. But both Walken and Cox are dynamic together in a movie that premiered before all of the above films yet remains a mostly unseen obscurity because of its sporadic distribution under various titles.

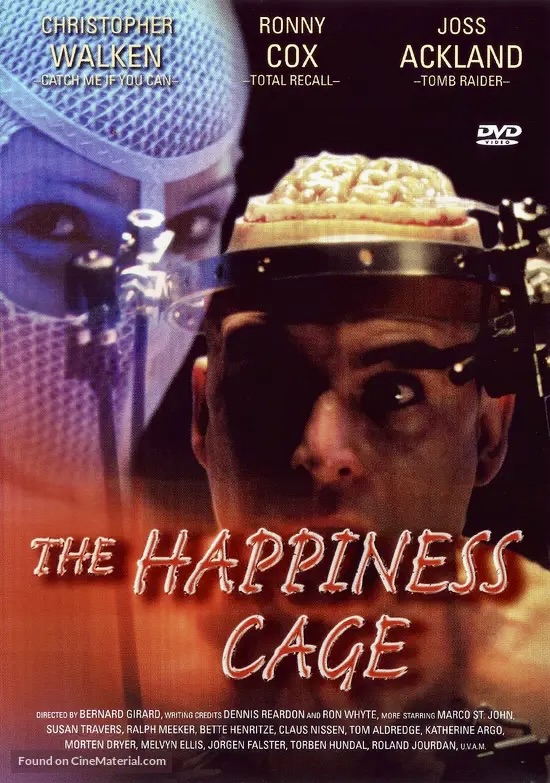

Initially released as The Happiness Cage in 1972 and then retitled The Mind Snatchers, this offbeat psychological drama never found an audience due to a confusing marketing campaign that seemed uncertain whether the movie was a sci-fi thriller, a horror film, an exploitation flick or an art house oddity. It also didn’t help that the movie was released in some markets as Brain Control and in others as The Demon Within. The director, Bernard Girard, was not well known to moviegoers despite a 20-year career of working mostly in television. Plus, the two leading players, Walken and Cox, were practically unknown at the time.

Continue reading