The title character of Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) is a donkey who goes through a series of owners in his sad life as a beast of burden.

Films about animals or featuring them as the main protagonists are usually the province of Walt Disney and other family friendly productions such as Benji (1974) and March of the Penguins (2005). Other than the horror genre, though, there have been relatively few departures from the usual formulaic approach to this type of movie with Jerome Bolvin’s dark satire Baxter (1989) and the ethnographic Story of the Weeping Camel (2003) being two of the rare exceptions. Yet nothing can really compare with Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), directed by French filmmaker Robert Bresson, which stands alone as a profound and singular achievement in this category.

A story about the life and death of a donkey called Balthazar (named after one of the three wise men in the Bible), Bresson’s film follows the animal from his childhood to his life as a beast of burden to his final days. The movie defies easy categorization and is open to multiple interpretations. Is it a religious allegory in the style of The Pilgrim’s Progress? A grim fable for adults on the complete indifference of the universe? A philosophical treatise by Bresson on his world view? A critique of French rural life in the acidic manner of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Le Corbeau (1947)?

A story about the life and death of a donkey called Balthazar (named after one of the three wise men in the Bible), Bresson’s film follows the animal from his childhood to his life as a beast of burden to his final days. The movie defies easy categorization and is open to multiple interpretations. Is it a religious allegory in the style of The Pilgrim’s Progress? A grim fable for adults on the complete indifference of the universe? A philosophical treatise by Bresson on his world view? A critique of French rural life in the acidic manner of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Le Corbeau (1947)?

A scene from Robert Bresson’s austere deconstruction of the Arthurian legend, Lancelot du Lac (1974).

It could be all of these things and more and that’s the extraordinary thing about Au Hasard Balthazar. It continues to yield deeper meanings and readings each time you see it. On the surface it has a deceptively simple storyline that follows in episodic fashion what happens to Balthazar as he is passed from one owner to the next. I first saw Bresson’s film in college in the 1970s after reading about it for more than a decade. Perhaps I expected too much but I found the film cold and detached. I recall feeling emotionally disengaged during the entire viewing experience but it was also only my second encounter with a Bresson film; the first was Lancelot du Lac (1974 aka Lancelot of the Lake), which is probably the most radical treatment of the Camelot legend ever made. That film was daunting enough thanks to the way it stripped away all the romance, excitement and passion of the famous story and focused instead on the iconography, sound effects of combat and movement of bodies in armor.

Jost (Charles Le Clainche, left) and Fontaine (Francois Leterrier) stage a daring prison break in Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped (1956).

It took me several years to fully appreciate Bresson and it began with A Man Escaped (1956), which I found to be an absorbing and emotionally exhilarating experience, despite the fact that most of it takes place in a prison cell. I followed that up with Diary of a Country Priest (1951), a film that I had previously bypassed as being too austere and meditative for my tastes. It proved to be a riveting human drama, driven by an intense, almost obsessively detailed depiction of a man stuck in a kind of spiritual purgatory, something Bresson was able to achieve with his remarkable eye for detail, or what J. Hoberman describes as “more precisely delineated off-screen space.”

Claude Laydu plays a man suffering from a crisis of faith in Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951).

Au Hasard Balthazar sets up its own idiosyncratic rhythm and tone from the opening credits which begin with Schubert’s Sonata No. 20, only to halt briefly for the loud braying of a donkey. We then see Balthazar as a young foal running free and playing with three children, one of whom is Marie, his owner (she is played by Anne Wiazemsky in her adult years). This idyllic time – probably the happiest period in Balthazar’s life – passes in a flash and then the years of servitude begin as a blacksmith solders horseshoes on him for hauling wagons and dragging tree stumps. The rest of Balthazar’s life is a parade of owners that goes from Marie’s father (Philippe Asselin), who has fallen on hard times on his farm, to Arnold (Jean-Claude Guilbert), the village derelict, to a circus where he is trained and promoted as “The Mathematical Donkey” (he answers questions by stamping out answers with his foot). Then he goes back to Arnold and later to a misanthropic merchant and landowner (Pierre Klossowski). Balthazar’s journey comes full circle when he is returned to Marie and later abducted by Gerald (Francois Lafarge), the delinquent son of the village baker (Francois Sullerot). Gerald plans to use the donkey to smuggle illegal goods across the border in a scheme that brings the movie to a tragic close.

Balthazar the donkey becomes a circus sideshow attraction in Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966).

Although Balthazar is the main protagonist, the story is not actually told from his point of view. Occasionally we may get a suggestion of what life looks like through his eyes. The most fascinating sequence is the donkey’s brief stint with a circus where he comes face to face with such caged animals as a tiger, a polar bear, a chimpaneze, an elephant; each of them considering the other with what could be empathy or disinterest. At other times, we observe Balthazar through the dispassionate eye of the camera, where he is either on the sidelines or the object of someone’s abuse or affection. Sometimes Bresson will switch the focus to the supporting characters in his story while Balthazar is offscreen somewhere, continually present in the viewer’s mind but not directly involved in the onscreen action.

A polar bear contemplates the donkey in front of his cage in Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), directed by Robert Bresson.

There is no attempt to get “inside” Balthazar’s head and thankfully no narrator or human voice to serve as the animal’s conscience. The fact that Bresson refuses to sentimentalize Balthazar in any way makes the movie more powerful because the moral judgement is placed on the viewer. When Gerard ties a newspaper to the donkey’s tail and sets it on fire because the animal refuses to budge from the side of a road, the cruelty is hard to bear but Bresson’s treatment of the scene is that of an impassive documentarian.

The donkey experiences a brief moment of tenderness from Marie (Anne Wiazemsky) in Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), directed by Robert Bresson.

You’ll notice in most cases Bresson’s refusal to use music to underscore a scene except in the most sparing manner – in the credit sequence, a brief scene of tenderness where Marie pats Balthazar’s head and the ending where the donkey, bleeding from a gun wound, expires slowly surrounded by a flock of sheep on a bucolic hillside. I had read that Bresson later regretted using music in that final scene because he felt it was too mawkish. Yet, without it, it would change the movie’s cumulative impact from something that is transcendent on a spiritual level to something bleak and bitter.

Nadine Nortier plays the title character in Robert Bresson’s Mouchette (1967), a portrait of a teenage suicide.

In her review of Bresson’s Mouchette (1967), Pauline Kael wrote that the director “has made several films of such sobriety that while some people find them awesomely beautiful, other people find sitting through them like taking a whipping and watching every stroke coming.” Her take on Au Hasard Balthazar is similar: “It’s a meditation on sin and saintliness. Considered a masterpiece by some, but others may find it painstakingly tedious and offensively holy.” While I don’t share the latter opinion (which is probably Kael’s honest reaction to the film), I can understand why some film critics and moviegoers don’t all share the same enthusiasm for Bresson’s work. He rewards the viewer with a certain kind of tough love, a mixture of formal rigor and exacting detail that can appear too cerebral or undramatized in its execution. Certainly, this is true of his approach to his actors, who are usually nonprofessionals or amateurs.

A scene from Werner Herzog’s Heart of Glass (1976) in which the director used hypnosis to shape the performances of the actors.

According to several interviews with actors who have worked with Bresson, he works hard to rid them of all affectation and artifice, breaking them down by having them recite their lines phonetically or read them without meaning or emotion. This sort of approach could backfire completely as in Werner Herzog’s Heart of Glass (1976), in which the director allegedly had the actors hypnotized for their performances. The story of a village that goes quietly mad after they lose the formula to their precious ruby glass, the film attempted to capture the same dream state of the on-screen characters but only produced a somnambulist state in the viewer. This is not the case with Au Hasard Balthazar as Bresson’s strict guidance of his nonprofessional cast achieves a kind of purity that bares the souls of his characters. This extends to Balthazar as well. Bresson insisted on working with an untrained donkey to get the effect he wanted. “It is not too frivolous to note that the quadruped gives one of the best Bressonian performances,” wrote Ronald Bergan and Robyn Karney, the editors of The Farber Companion to Foreign Films.

Pierre Klossowski plays one of the less sympathetic owners of the title donkey in Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966).

Among Bresson’s many films, Au Hasard Balthazar has probably been the most universally praised by major film critics as well as such influential cinema legends as writer/director Marguerite Duras and Jean-Luc Godard, who called it “the world in an hour and a half.” Yet everyone seems to have their own interpretation of the movie’s true meaning. French filmmaker Louis Malle said, “To me it’s essentially a film about pride. What drives absolutely all the characters is pride. A kind of haughtiness about their condition and their fellow men and even about the world.” Manny Farber called it, “a rich catalog of mythology and symbolism about donkeys squeezed into a queer script that wanders and doubles back, detailing the varieties of evil and self-destruction that Bresson seems to be saying is Human Nature…this is a superb movie for its original content…that creates a deep, damp, weathered quality of centuries – old provincialism.”

A bunch of rural hooligans exploit a donkey in their drug-running operation in Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), directed by Robert Bresson.

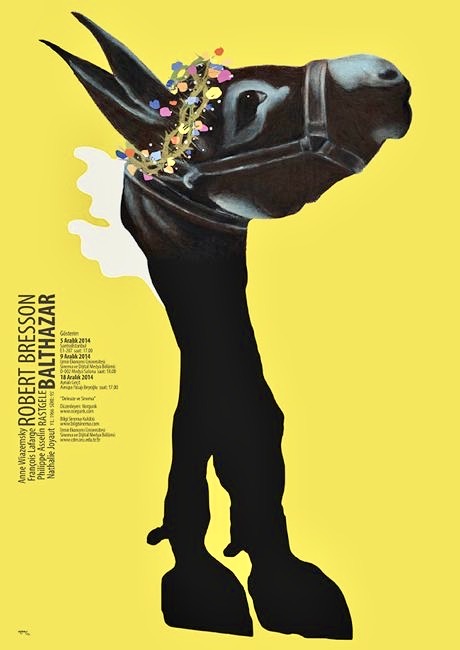

In his reference work Eighty Years of Cinema, Peter Cowie described Au Hasard Balthazar as “a wise and graceful tale of a donkey that embraces pastoral love and vicious beatniks without ever being ridiculous.” David Thomson in Have You Seen….?: A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films, wrote “Can anyone film a donkey without summoning up that unquenchable (if absurd) affection for any placid animal beset by man, kind or unkind?…We do not know how to look at such creatures without abandoning scrutiny or objectivity. It’s not that Bresson’s austere style – with quick dissolves here, going from one time to another without connecting the two – ever comes close to a kind of Black Beauty for donkeys. But one look at those large, sad eyes – why do I call them sad? – and we are suckers.”  J. Hoberman of The Village Voice offers this: “Oblique as it is, Bresson’s narrative hints at an immense story involving betrayal, theft, even murder. But it real concern is the state of being. Crowned with flowers, spooked by firecrackers, struck without cause, Balthazar bears patient witness to all manner of enigmatic human behavior…This expressionless donkey is the most eloquent of creatures – he is pure existence, and his death, in the movie’s transfixing final sequence, conveys the sorrow that all existence shares.”

J. Hoberman of The Village Voice offers this: “Oblique as it is, Bresson’s narrative hints at an immense story involving betrayal, theft, even murder. But it real concern is the state of being. Crowned with flowers, spooked by firecrackers, struck without cause, Balthazar bears patient witness to all manner of enigmatic human behavior…This expressionless donkey is the most eloquent of creatures – he is pure existence, and his death, in the movie’s transfixing final sequence, conveys the sorrow that all existence shares.”

Director Robert Bresson (right) instructing his actors and crew on the set of Au Hasard Balthazar (1966).

In an interview, Bresson gives us his own interpretation of the film: “Au Hasard Balthazar is about our anxieties and desires, when faced with a living creature who’s completely humble, completely holy, and happens to be a donkey: Balthazar. It’s pride, greed, the need to inflict suffering, lust in the measure found in each of the various owners at whose hands he suffers and finally dies. This character resembles the Tramp in Chaplin’s early films, but it’s still an animal, a donkey, an animal that evokes eroticism. Yet at the same time evokes spirituality or Christian mysticism because the donkey is of such importance in the Old and New Testaments as well as all our ancient Roman churches. Balthazar is also about two lines that converge, lines that sometimes run parallel and sometimes cross….the first line: in a donkey’s life, we see the same stages as in a man’s: a childhood of tender caresses, adult years spent in work for both man and donkey. A little later, the time of talent and genius, and finally, the stage of mysticism that precedes death. The other line is the donkey at the mercy of his different owners, who represent the various vices that bring about Balthazar’s death and suffering.”

A donkey’s suffering comes to an end in the final moments of Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966).

Even though I have ended with Bresson’s take on his film, I don’t think there will ever be a definitive interpretation of Au Hasard Balthazar and that is a wonderful thing in itself.  Au Hasard Balthazar was first released on DVD in the U.S. by The Criterion Collection in 2005. In May 2018 Criterion offered a new 4k digital restoration of the film on DVD and Blu-Ray. The supplementary features include a 2004 interview with film scholar Donald Richie, Un Metteur en ordre: Robert Bresson, a 1966 French TV program on the film featuring director Bresson, members of the film’s cast and crew and other interviewees, a trailer for the film and an essay by James Quandt.

Au Hasard Balthazar was first released on DVD in the U.S. by The Criterion Collection in 2005. In May 2018 Criterion offered a new 4k digital restoration of the film on DVD and Blu-Ray. The supplementary features include a 2004 interview with film scholar Donald Richie, Un Metteur en ordre: Robert Bresson, a 1966 French TV program on the film featuring director Bresson, members of the film’s cast and crew and other interviewees, a trailer for the film and an essay by James Quandt.

Other websites of interest:

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/370-au-hasard-balthazar

http://sensesofcinema.com/2002/great-directors/bresson/

https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/where-begin-robert-bresson

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/oct/10/anne-wiazemsky-obituary

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R8_Db2r_dCM