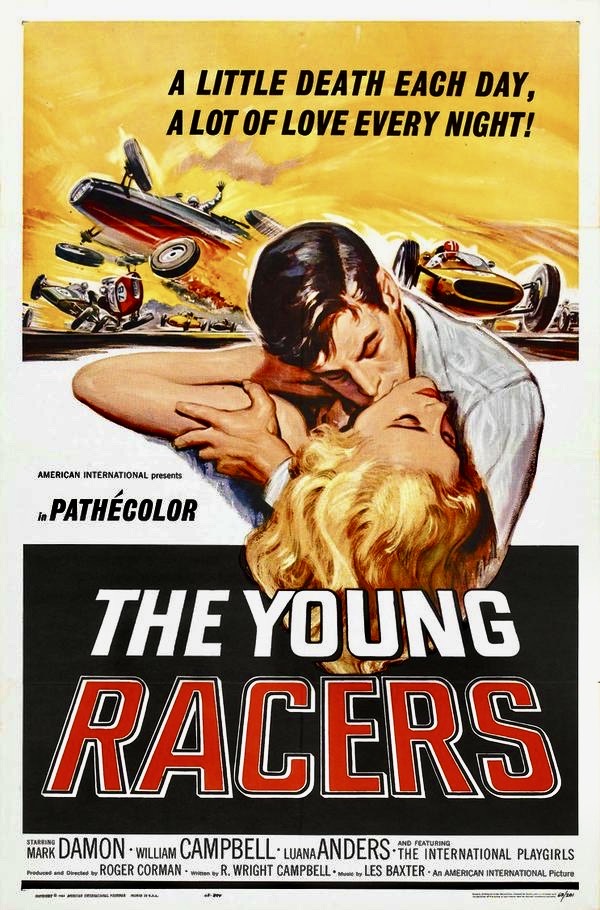

In 1966 director John Frankenheimer, a race car enthusiast, was able to realize a long-cherished dream: to make a film about the Grand Prix racing circuit focusing on several drivers and their personal lives off the track. The result, Grand Prix, is still considered the ultimate racing film, due to its spectacular cinematography that puts the viewer in the driver’s seat with its Cinerama format, split-screen technique and immersive audio. According to the director, it cost about $10.5 million to make, was a box office hit and garnered three Oscars for Best Sound, Best Film Editing and Best Sound Effects. What many people failed to notice was that director Roger Corman had already made a film about the Grand Prix racing circuit three years earlier entitled The Young Racers (1963), which was made on location in Europe like Frankenheimer’s epic with exciting racing footage from Monte Carlo, Monaco, Rome, Rouen (France) and Spa (Belgium) and it cost less than half a million to make. Sure, it was a B-movie from American International Pictures (AIP) but it had a glossy, big budget look to it unlike the typical AIP product and it added some invocative twists to a formulaic genre film that often seemed influenced by the aesthetics of the French New Wave (Corman has always been a fan of European art cinema).

Continue readingLily in Wonderland

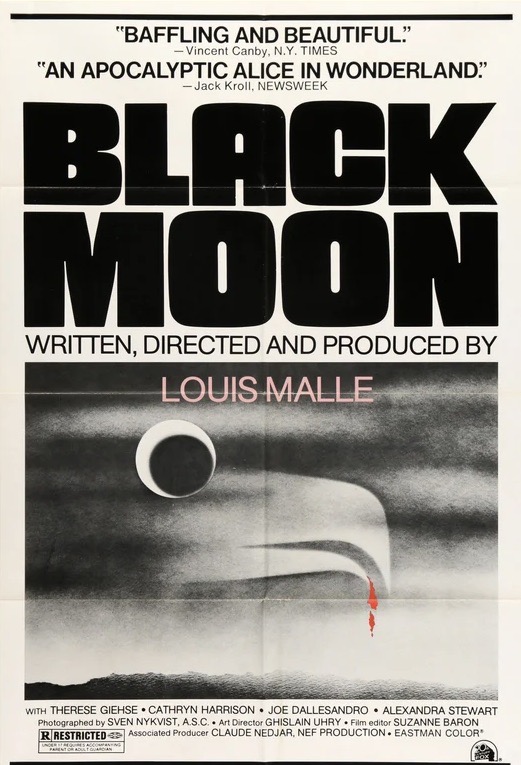

Louis Malle has never been the sort of filmmaker critics could easily pigeonhole in terms of his style and interests. He’s worked in practically every film genre (thriller, social satire, melodrama, documentary, etc.) and his restless curiosity has led him to explore a vast array of subjects from underwater life (The Silent World, 1956) to sexual liberation (The Lovers, 1958) to life under the Nazi occupation (Au Revoir, Les Enfants, 1987). Yet, for even an iconoclast like Malle, his 1975 film Black Moon is unlike anything he’s ever done before or since. “Opaque, sometimes clumsy, it is the most intimate of my films,” he once said. “I see it as a strange voyage to the limits of the medium, or maybe my own limits.”

Continue readingKiju Yoshida’s Escape from Japan

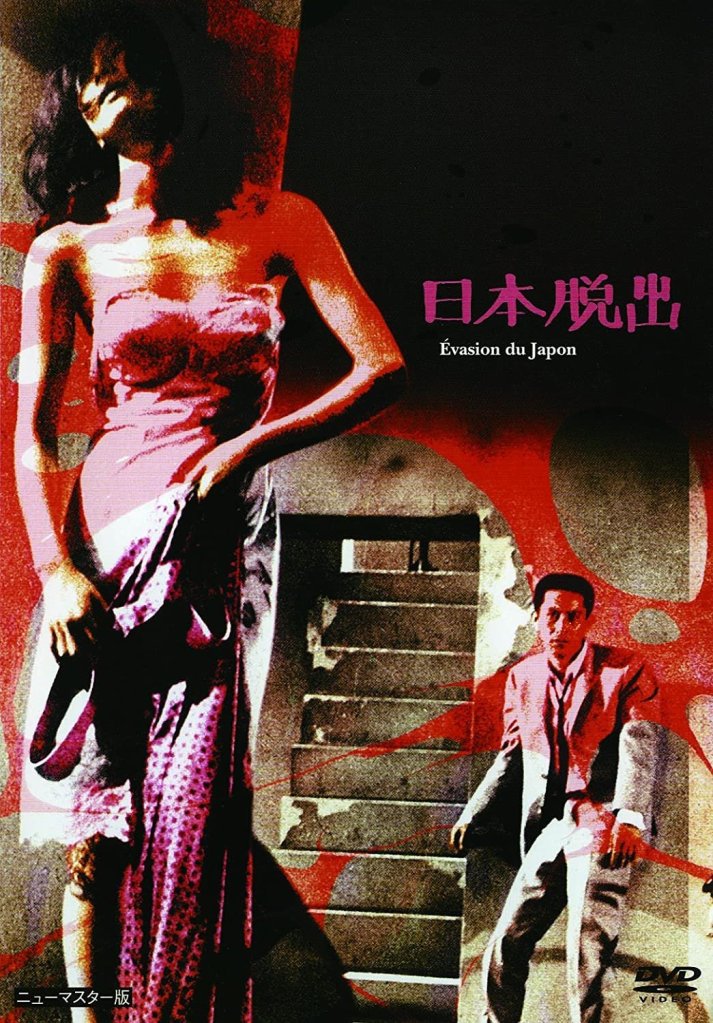

The Japanese New Wave of the late 1950s/early 1960s introduced the world to a number of rising directors who are now icons of cinema like Nagisa Oshima, Hiroshi Teshigahara, Shohei Imamura and Masahiro Shinoda but it has only been in recent years that Yoshishige Yoshida aka Kiju Yoshida has started to receive the belated acclaim he deserves. His 220-minute masterpiece Eros + Massacre (1969), which told the parallel stories of two student activists and Sakae Osugi, an anarchist and free love advocate, startled critics with its radical take on sex and politics, not to mention a fragmented narrative approach with unusual camera compositions of widescreen black and white imagery. Long before that, Yoshida learned his trade at Shochiku Studio at a time when the company began making films about the disaffected post-war generation such as Oshima’s Cruel Story of Youth (Seishun Zankoku Monogatari, 1960) and Good-for-Nothing (Rokudenashi, 1960), Yoshida’s debut film about an aimless youth and his attraction to the secretary of a rich friend’s father. The director would eventually part ways with Shochiku over creative differences and start his own production company in 1964 but his final movie for the studio, Escape from Japan (Nihon Dasshutsu, 1964), shows Yoshida imposing his own aesthetic and stylistic approach to what is essentially a B-movie melodrama.

Continue readingAnything for a Laugh

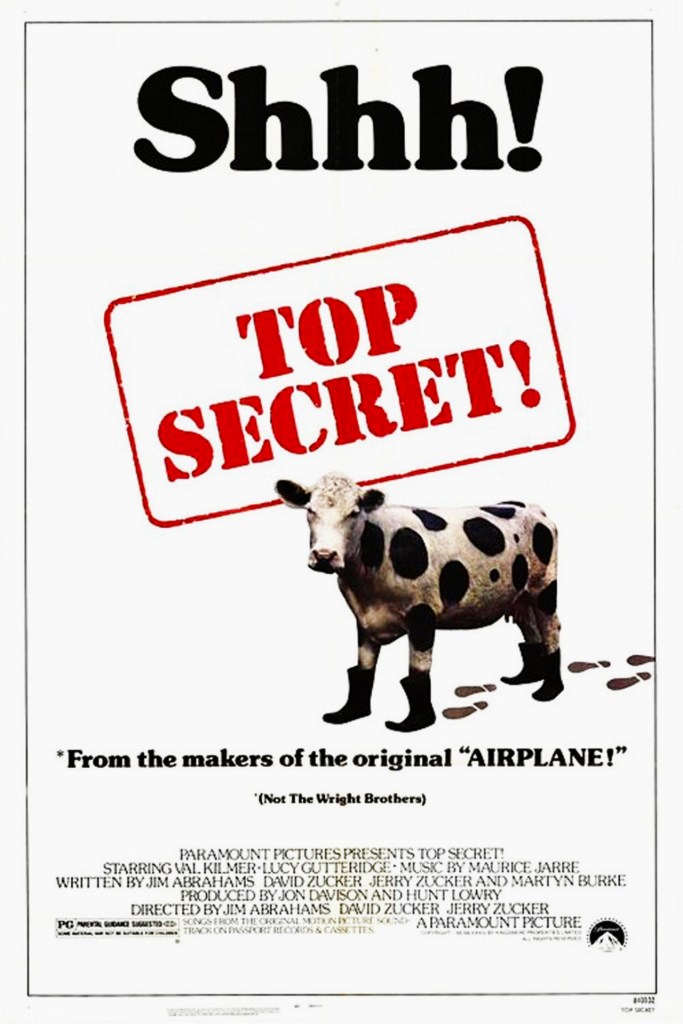

How many movie spoofs can you name which poke fun at World War II espionage dramas AND rock ‘n’ roll musicals? There’s only one and it’s also notable as Val Kilmer’s screen debut – Top Secret! (1984). The follow-up film to Airplane! (1980), their enormously successful parody of disaster flicks, Top Secret! was the third collaboration between Jim Abrahams, David Zucker and his brother Jerry and employs the same anything goes style of that previous hit and their first film, The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), which the trio co-wrote but John Landis directed. In other words, outrageous sight gags, terrible puns, anachronisms, broad slapstick, politically incorrect humor and silly pop culture parodies.

Continue readingA Filmmaker in Self-Imposed Exile

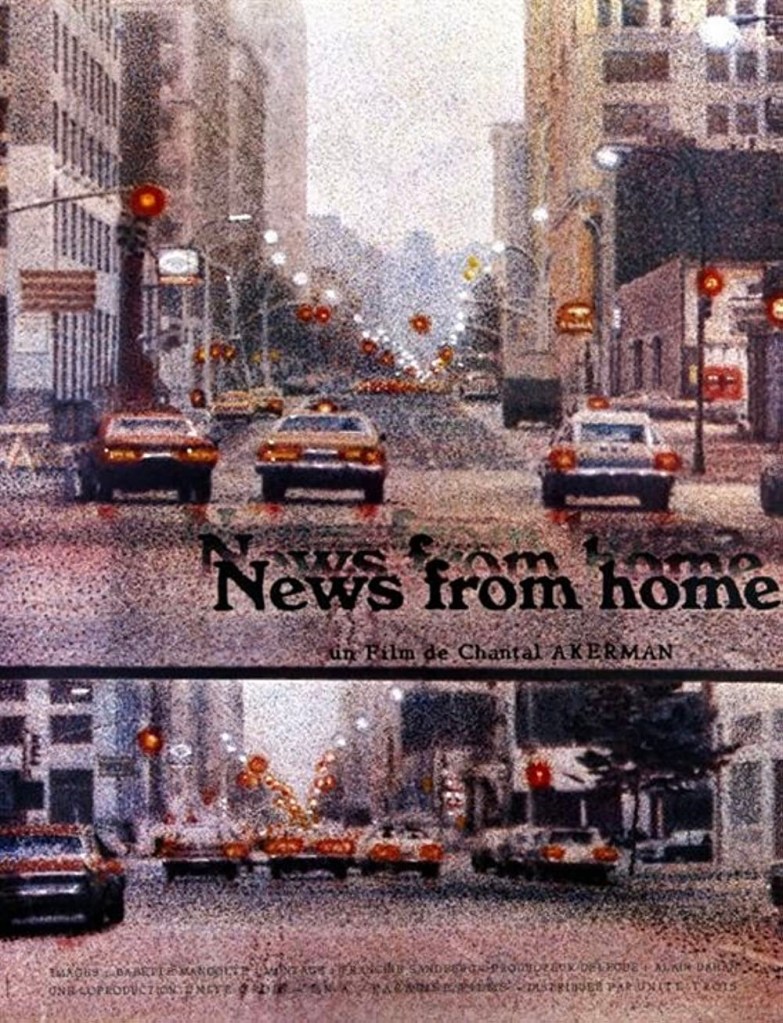

In the mid-1970s tourists were being warned by a concerned group of local citizens in New York City to steer clear of the Big Apple via a pamphlet campaign. Crime had risen dramatically since the late sixties, the city was reeling from a number of political and economic crises including a mass garbage workers’ strike, and unemployment was at an all time high, driving many residents to leave for the suburbs. The media began to refer to Manhattan as “Fear City” and actress Shirley MacLaine was quoted as saying NYC was “the Karen Quinlan of cities” (a reference to the teenager who lapsed into a coma in 1975 and lived in a permanent vegetative state for ten years before dying from pneumonia). It was during this period that Belgium filmmaker Chantal Akerman created one of her most personal and acclaimed films during a 1976 visit. News from Home is an autobiography of sorts and the director was no stranger to the city. She had lived there in 1971 but her movie is not a tourist’s view of the city. It shows us the kind of gritty urban environment that Martin Scorsese immortalized in 1976’s Taxi Driver.

Continue readingClu Gulager in Sweden

Holdenville, Oklahoma native Clu Gulager was an extremely busy and prolific actor (over 160 TV and movie credits) who worked right up to his death at 93 in August 2022. Even if he never quite graduated to the A list of Hollywood actors, he will always be remembered for starring roles in two iconic TV westerns, The Tall Man (1960-62), as Billy the Kid, and The Virginian (1963-68) as Sheriff Emmett Ryker as well as several cult movies. Among them are his feature film debut opposite Lee Marvin as a pair of sociopathic hit men in the 1964 remake of The Killers, directed by Don Siegel, The Return of the Living Dead (1985), Dan O’Bannon’s macabre zombie comedy, and A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985). Other notable roles include memorable parts in the Paul Newman racetrack drama Winning (1969), Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971) and McQ (1974), a John Wayne cop thriller, but if American audiences had been given an opportunity to see him in the 1974 Swedish film Gangsterfilmen (U.S. title: Gangster Film aka A Stranger Came by Train), they would surely rank it right up there with his intimidating but off-the-wall performance in The Killers, which should have made him a major star.

Now You See Him, Now You Don’t

Ever notice how every secret agent in the movies seems to have a gimmick? Well, Perry Liston – code name: Matchless – has got a winner. When confronted with unavoidable capture or certain death from enemies, he can literally vanish into thin air. He’s not superhuman though. His ability to become invisible at will is completely dependent on a unique ring given to him by a fellow prisoner in a Chinese jail. And the ring’s powers are limited: it can only be used once every 10 hours and the wearer can expect his invisible state to last no more than twenty minutes. Those are the rules and Matchless (1966), a quirky genre offering from Italy, plays fast and loose with the gimmick [In some markets it was released under the title Mission TS (Top Secret)].

Continue readingMetamorphosis of a German Housewife

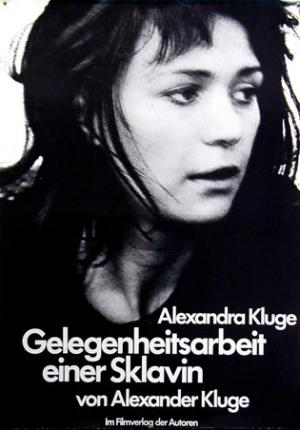

When German director Alexander Kluge first burst upon the international film scene in 1966 with his debut feature Abschied von Gestern – (Anita G.) aka Yesterday Girl, he was at the forefront of the emerging New German cinema. The movie was proclaimed “Outstanding Feature Film” at the 1967 German Film Awards with Kluge also winning for “Best Direction” and it also won numerous awards at the Venice Film Festival. After such a glorious beginning, Kluge was soon overshadowed by R.W. Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders and other rising German directors as their work enjoyed wider acclaim and distribution outside Germany. That certainly didn’t discourage Kluge from moviemaking and his filmography to date includes more than 100 shorts, features and TV movies, most of which have been criminally overlooked by the same film critics who embraced his more famous peers. Yesterday Girl earned him the moniker of “The German Godard” and you can see stylistic similarities between the two directors but Kluge forged his own personal brand of cinema and one of his most important and audacious works is Gelegenheitsarbeit einer Sklavin (English title: Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave, 1973).

Continue readingThe Birthplace of Jazz

How’s this for a dynamite screen team – Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong? They appear together and separately in New Orleans (1947), a fictitious love story set during the end of the Golden Age of jazz circa 1917 – the year Storyville ceased to be the Crescent City’s hot spot.

Continue readingThe Kidnapped Heiress

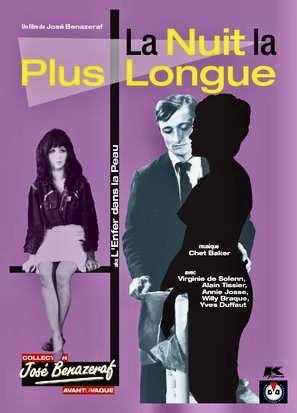

When it comes to crime films, what’s your pleasure? The genre breaks down into so many sub-categories that it helps if you have a particular theme in mind. Bank Heists? Home Invasions? Police procedurals? Gang wars? How about kidnapped heiresses? James Hadley Chase’s 1939 pulp fiction novel No Roses for Miss Blandish is a classic example of this edgy situation and has been adapted for films at least twice – the 1948 British noir of the same title starring Jack La Rue and The Grissom Gang (1971), Robert Aldrich’s violent remake with Kim Darby as the unfortunate victim. Even real-life cases involving kidnapped heiresses have inspired numerous crime dramas such as the 1974 kidnapping of Patty Hearst which spawned Abducted (1975), a sleazy exploitation rip-off from director Joseph Zito, The Ordeal of Patty Hearst, a 1979 made-for-TV dramatization, Patty Hearst (1988), Paul Schrader’s take on the events with Natasha Richardson in the title role, and probably the best of the lot, Robert Stone’s 2004 documentary, Guerrilla: The Taking of Patty Hearst. But, if you want to see an arty, minimalistic treatment of the kidnapped heiress theme with erotic interludes and a cool jazz score by trumpeter Chet Baker, look no further than L’enfer dans la peau (1965), a French softcore crime drama from director/writer/producer Jose Benazeraf, and released in the U.S. in an edited form entitled Sexus.

Continue reading