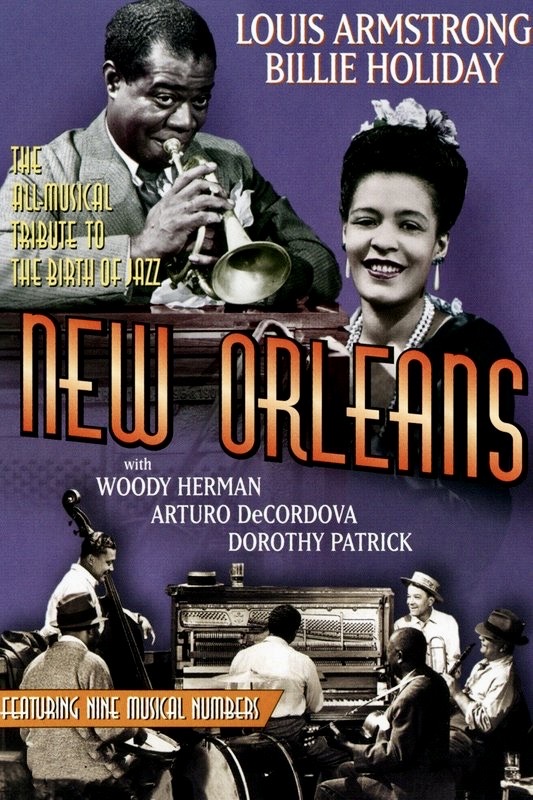

How’s this for a dynamite screen team – Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong? They appear together and separately in New Orleans (1947), a fictitious love story set during the end of the Golden Age of jazz circa 1917 – the year Storyville ceased to be the Crescent City’s hot spot.

Unfortunately, Holiday and Armstrong are not the stars. Those duties fall to Dorothy Patrick as a high-society girl and Arturo de Cordova as the man of her dreams, a jazz connoisseur who just happens to own the most elegant casino on Basin Street. Their love affair encounters major resistance from Patrick’s class-conscious parents who disapprove of their daughter’s enthusiasm for the emerging music scene on the poor side of town. In one of the more outlandish plot turns, history is rewritten to add a little drama to the romance – Patrick’s mother uses her political connections to shut down Storyville and force de Cordova to close his cabaret.

More interesting for what it could have been instead of what it is, New Orleans started off as a starring vehicle for Holiday and Armstrong, cast as jazz artists who leave the south to seek their musical fortunes elsewhere. Through each new rewrite of the script, however, their parts became less and less prominent until they were finally reduced to secondary characters while a new storyline was fashioned around a romance between a white opera singer and a white club owner known as the “King of Basin Street.”

Typical of Hollywood’s treatment of many black entertainers during this era, this “new, improved” version of New Orleans was obviously based solely on box-office considerations; the studio was afraid southern theater owners wouldn’t book the film with black actors in the leads during the Jim Crow era, but it was also true that the largest majority of moviegoers in America at that time were white and not that interested in black culture or jazz musicians.

In an ironic twist of fate, Billie Holiday, who had managed to avoid domestic service – the only work available to most black women – for most of her life, now found herself cast as a servant. According to Donald Clarke in his biography, Wishing on the Moon: The Life and Times of Billie Holiday, she didn’t want to turn down an opportunity to appear in a motion picture and told composer/journalist Leonard Feather, “I’ll be playing a maid, but she’s really a cute maid.”

Once production began, Holiday created a few problems on the set due to her frequent tardiness, but the studio musicians didn’t mind since they were getting paid for any overtime. Leading lady Dorothy Patrick also reportedly complained to Arthur Lubin that Holiday was a shameless scene-stealer. The director, however, recognized Lady Day’s genuine artistry and later commented that Holiday made Dorothy Patrick look like “a hole in the screen.” To demonstrate Lubin’s point, just compare Holiday’s rendition of “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans” with Ms. Patrick’s performance of the number.

Although Holiday shines in her brief scenes in New Orleans, the film provides a much more prominent showcase for Louis Armstrong, who had already appeared in ten feature films prior to this (Holiday only made one previous film short, Symphony in Black, 1935). It’s a rare opportunity to see the real “King of Basin Street,” strutting his stuff alongside another New Orleans jazz legend – Kid “Ory” – while performing some of that city’s most famous and representative songs – “New Orleans Stomp” (written by Joe “King” Oliver), “Buddy Bolden’s Blues” (written by Jelly Roll Morton), “West End Blues,” “Shim-Me-Sha-Wabble,” “Basin Street Blues,” and many more. Armstrong’s duet with Holiday on “The Blues Are Brewin’,” though, might be the showstopper.

As an attempt to tell the history of jazz through a love story that spans forty years, New Orleans is a laughable failure. But as a visual and aural record of two of the most influential musical talents in the history of jazz, the film is a must-see. Jazz aficionados will also enjoy spotting other legendary musicians in the background – Woody Herman and His Orchestra, Barney Bigard, Russell Moore, Charlie Beal, Zutty Singleton, and Lucky Thompson to name a few. And, yes, that is Shelley Winters in a minor role, playing Arturo de Cordova’s secretary.

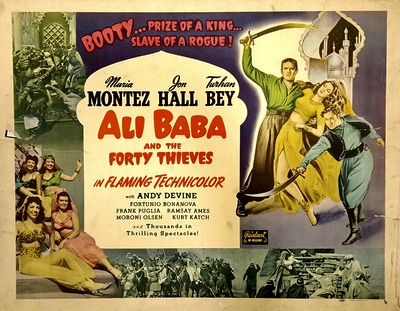

As a long time contract director for Universal, Arthur Lubin might seem like an odd choice as director for New Orleans, an independent production distributed by United Artists, but he was an expert at helming low-budget pictures and turning them into box office gold. He entered the film industry as an actor in 1924 and moved into the director’s chair ten years later, making programmers for Monogram and Republic Studios. Lubin started directing B picture genre films for Universal in 1936 but when his 1941 army comedy Buck Privates (1941) starring the comedy team of Bud Abbott and Lou Costello became one of the studio’s biggest hits of the year, Lubin was given better assignments such as the lavish 1943 remake of Phantom of the Opera and the exotic Maria Montez-Jon Hall Technicolor fantasy Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1944).

New Orleans was made between the comedy-fantasy Night in Paradise (1946) with Merle Oberon and Turhan Bey and the underrated film noir Impact (1949). In the early 1950s Lubin became the go-to director for a series of Francis, the Talking Mule pictures and then moved into television in 1958, directing such popular series as 77 Sunset Strip, Maverick and Mr. Ed – another talking animal franchise! – of which he helmed 131 episodes. One of his final feature film credits was the Don Knotts comedy-fantasy The Incredible Mr. Limpet (1964). Lubin died in 1995 at the age of 96 but a disturbing factoid on the IMDB website intimated that the director may have been a “victim of Efren Saldivar, a respiratory therapist and self-described mercy-killer and “angel of death,” who confessed to killing dozens of seriously ill hospital patients by lethal injection at the Adventist Medical Center in Glendale, CA, beginning in 1989. Lubin was in a coma when he died.”

New Orleans had previously been available on VHS but in April 2000 Kino Video (now Kino Lorber) released the film on DVD with the added musical shorts A Rhapsody in Black and Blue (1932) featuring Louis Armstrong and Symphony in Black (1935) with Billie Holiday. The Kino release is now out of print but you might be able to still find copies available from online sellers.

*This is a revised and updated version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.

Other links of interest:

https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/bios/Holiday__Billie

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-arthur-lubin-1620162.html