Hammer Studios, home to vampires, werewolves, mummies, Quatermass Xperiments, pirates….and child molesters? In 1960, the British film production company (originally founded in 1934), ventured into decidedly new territory from their usual formulaic mix of horror films, suspense thrillers and costume adventures. Never Take Candy from a Stranger (known as Never Take Sweets from a Stranger in the the U.K.) was Hammer’s attempt at a serious adult drama that addressed a controversial topic most major studios wouldn’t touch at that time.

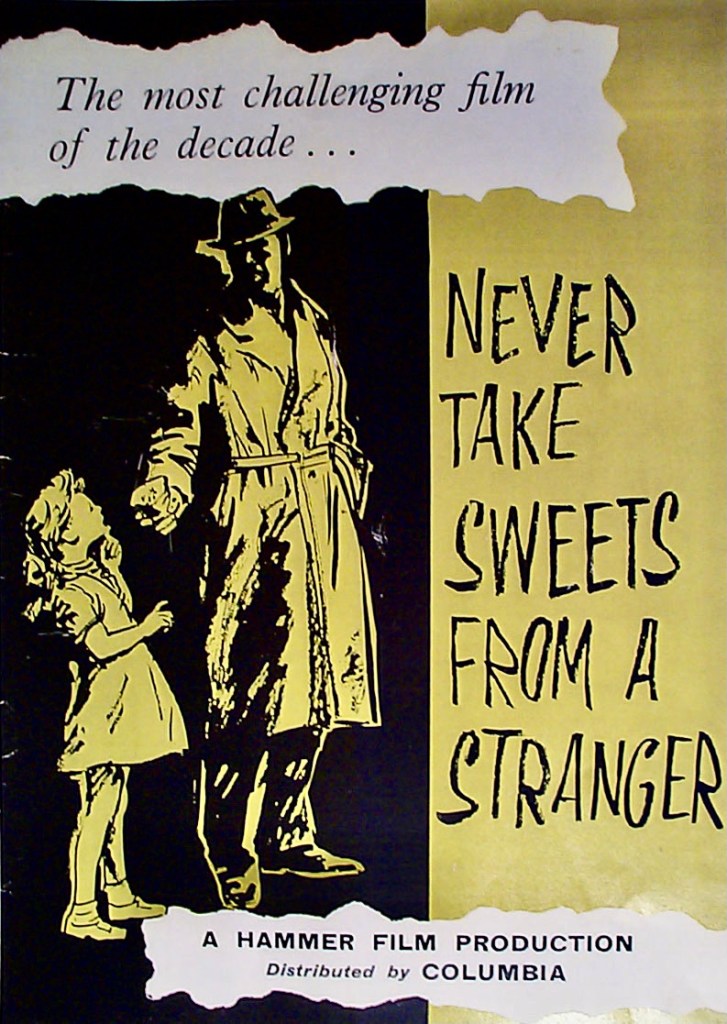

One has to admit that from a financial standpoint, social issue films rarely draw blockbuster crowds because the average moviegoer wants escapism from the movies, not disturbing reflections of real life or thought-provoking message films. There have been exceptions to the rule, of course, that are usually based on topicality and big name stars such as Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones and On the Beach, but a film about child molestation in 1959 was not going to be an easy sell. Hammer Studios knew this and approached it in that light, designing one poster that proclaimed “The most challenging film of the decade…” with a pulp fiction-like cover drawing of a hesitant child pondering an outstretched hand holding candy and the gift giver depicted as a shadowy character in a trenchcoat.

The film’s trailer was even more emphatic in its intent, opening with the scroll: “An extraordinary announcement from the management…This is the first time we have ever presented a story of this kind. Because it has been told so delicately we believe every adult will want to see it.” As for the film itself, a short disclaimer appeared at the head in case any Brit became concerned that this was an internal social problem in England alone: “This story – like its characters – is fictitious. It is set in Canada. But it could happen anywhere and it could be true.”

Never Take Candy from a Stranger turned out to be a resounding box office failure, even though it featured a first rate cast of British character actors, several of them Hammer film regulars, Freddie Francis’s crisp, evocative black and white cinematography (he lensed it just prior to his Oscar-winning work in Sons and Lovers), Cyril Frankel’s taut direction and an intelligent screenplay by John Hunter (adapted from Roger Garis’s play, The Pony Cart). None of this seemed to make a difference because the movie-going public didn’t want to see a movie about a sex pervert with a thing for little girls.

It also didn’t matter than the film was non-explicit in its visual depiction of the latter.It was simply the idea that most people found revolting but Hammer deserves credit and kudos for producing a frank and disturbing movie, a genuine horror film for adults “that could happen to anyone with children.” Occasionally it does become didactic in its cause and effect scenario of the accuser and the accused when they land in court and the film threatens to turn into a glorified A/V-classroom film of the fifties with a serious topic dramatized for maximum impact.

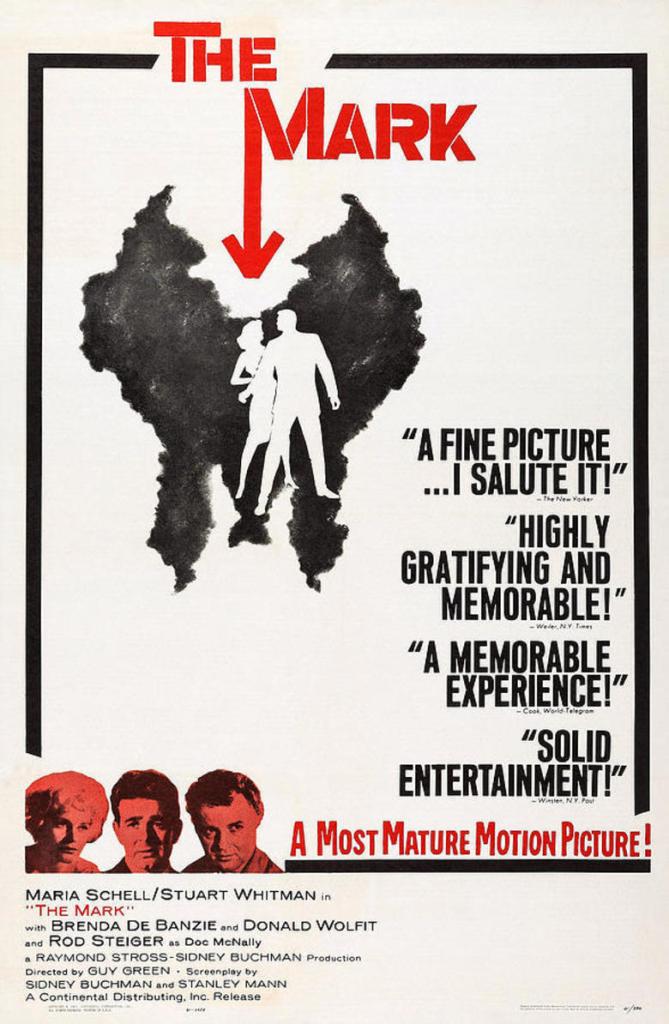

Overall though the final effect is chilling and the dénouement appropriately grim. Interestingly enough, another film about child molestation (also made in Great Britain) was released in 1961 – The Mark. This one focused instead on a former child molester trying to put his life back in order and was an unusually sympathetic treatment of the accused (Stuart Whitman received a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his performance). Never Take Candy from a Stranger offers a reverse viewpoint where the audience empathize completely with the victim and her family. The pedophile is also clearly presented as a suitable case for treatment and permanent lockup.

Never Take Candy from a Stranger immediately draws you in with a bucolic overhead view of two little girls playing on a rope swing deep in the forest. We soon realize we are seeing the little girls through the viewpoint of someone in a nearby house who has spotted them through his binoculars. The little girls, Jean (Janina Faye) and Lucille (Frances Green), interrupt their fun when one of them loses her purse in the tall grass. When Jean complains she can’t find her candy money, Lucille tells her, “I know where you can get candy for nothing” and leads her toward the mansion at the edge of the woods, setting up the creepy scenario that follows as the title sequence begins.

We soon learn that Jean’s parents, Sally and Peter Carter (Gwen Watford and Patrick Allen) are new to the village, with Peter stepping into the prestigious position of head principal of the local high school. We also see Jean return home after her adventure in the woods with Lucille and mention that she hurt her foot by stepping on a nail. No puncture wound is evident but her remark leads to further questions from her parents, who not only learn that she was playing barefoot but had been invited into the home of Clarence Olderberry Sr. (Felix Aylmer) who gave the girls candy for playing a game with him – a game that required them to dance naked in front of him.

Part of the film’s unsettling nature is that instead of visualizing these events, it becomes much worse in our imaginations as it is described to us by little Jean. Later, Jean’s mother gets additional details from her daughter, telling her husband and mother-in-law Martha (Alison Leggatt): “He just sat there a few feet away, Jean said. He kept smiling at them, rocking back and forth as if he was singing – only it wasn’t singing…After a few minutes he closed his eyes and Jean thought he’d gone off to sleep. She started to put on her clothes again but he woke up and asked her what she was doing. She said she was cold and thought the game was finished. He laughed and told her it was and to go and get another box of candy.” The final kicker is that Jean complained that “the candy wasn’t very good.”

Disbelief and shock from the parents soon gives way to outrage and anger and Never Take Candy from a Stranger quickly escalates into a bitter courtroom drama for the first two-thirds of the narrative with the Carter family pitted against the Olderberry family, who not only own the town and employ most of the local people in their family business but effectively use their power to try and prevent the village residents from taking sides with the Carters. It doesn’t matter that Clarence Olderberry Sr. has a history of incidents involving other children; his power and influence have discouraged anyone from bringing charges against him until now. His son even angrily confronts the Carters, saying, “You lousy outsiders. You come here without knowing a soul looking for a job. We find you one and the first thing you do is stir up trouble. You start talking about getting people arrested and having them shut up.”

The local police sergeant isn’t much better and is patronizing to Jean’s mother when she tries to file a complaint, dismissing the old man’s behavior as nothing more than getting “a little fresh.”

Sally Carter: “A little fresh? You call a little fresh getting little girls to strip in front of him?”

Policeman: “Well, nobody was hurt were they? He didn’t do anything.”

Sally: “Yes, he did do something. He attacked their innocence and I don’t mean their physical innocence. I mean their minds and the only reason he didn’t succeed was because they were too young and inexperienced to know what he was after.”

Policeman: “In other words, so no real harm’s been done?”

Sally: “I didn’t say that.”

Policeman: “That’s what it’s going to sound like if you force this issue and it comes out in an open court.”

[Spoiler alert] The trial goes badly for the Carters who didn’t properly prepare their daughter for the brutal cross-examination by the Olderberry’s defense attorney. As played by Niall MacGinnis (Curse of the Demon) with diabolical relish, he easily confuses the girl, casts suspicion on her testimony and credibility and causes her to collapse in tears. The story doesn’t end here of course and I won’t divulge any further information about the final third except to say that it enters pure Hammer horror territory as the elderly pervert is free to return to his nasty habits which he does with undisguised glee. In fact, the final 20 minutes are genuinely harrowing, especially if you are parents.

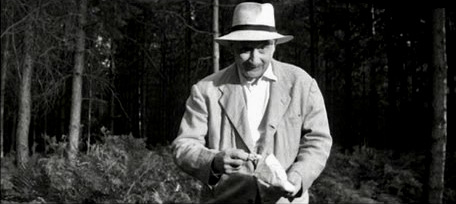

The performances are well crafted all around and Janina Faye is particularly convincing as the traumatized Jean (Faye would later successfully make the transition to leading lady appearing mostly in British television productions). Most memorable of all though is Felix Aylmer as Olderberry Sr., who isn’t really seen close-up until the trial sequence in which he comes across as a befuddled and sad old man. It’s not until we see him later, stalking his prey through the woods, his face a mask of ecstatic sexual depravity, that his visage becomes truly nightmarish. The fact that he never utters a word the entire film only reinforces his disturbing presence and makes him as monstrous in his own way as James Arness as The Thing or Christopher Lee in Dracula: Prince of Darkness. Aylmer reminds me somewhat of Albert Fish in appearance; Fish was a notorious child molester, murderer and cannibal who boasted of killing up to 100 children though he was only convicted of three murders (he was executed by electric chair in 1936).

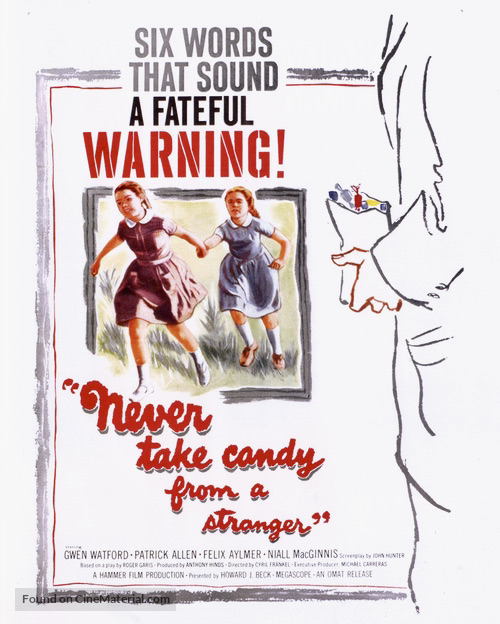

Released during the same year as other Hammer productions like The Mummy, The Stranglers of Bombay, Hell is a City and The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll (aka House of Fright), Never Take Candy from a Stranger was treated like the typical exploitation film and got no respect from the critics. It didn’t help that Hammer publicity issued one version of the poster with a garish image and the tagline “A Nightmare Manhunt For Maniac Prowler!”

The London Times wrote “It must be condemned as a film that never should have been made!” The Sunday Express noted, “The treatment is too glib, its style too melodramatic, an easy profit out of an important but nasty subject.” And Films and Filming reported, “A smart production veneer might fool people into thinking that here is a wholly adult film concerned with social and moral problems. It isn’t! In years to come, film historians will no doubt be able to logically explain the success of this company dealing only with the lurid and the loathsome.”

Despite this, the movie received some positive reviews as well. Variety called it “a sincere, worthy, restrained, and exceedingly well done job which should be seen by every parent and child.” Even the usually ultra-conservative National League of Decency made the statement that “This is a perennial social problem treated with moral caution and without sensationalism.”

Unfortunately, audiences stayed away in droves and convinced Hammer studio heads to never attempt another serious message movie and stick with imitating their past successes such as Horror of Dracula and The Curse of Frankenstein. Screenwriter/producer and occasional director Michael Carreras (The Lost Continent, Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb) later said, “The moment the film came out the critics said, ‘Oh, here we go – look at Hammer taking a social problem and capitalizing on it.’ There was never any attempt to exploit the subject.”

Prior to the release of Never Take Candy from a Stranger, there was another film from West Germany that addressed the threat of child molesters and was just as creepy. It Happened in Broad Daylight (Es geschah am hellichten Tag, 1958), directed by Ladislao Vajda, features Michel Simon as an elderly peddler who is falsely arrested by the police for the sex murder of a little girl. The film becomes a tense police procedural drama as the real suspect continues his reign of terror. Based on a novel by Friedrich Durrenmatt, It Happened in Broad Daylight co-stars Heinz Ruhmann, Sigfrit Steiner and Gert Frobe, who reputedly was cast as the lead villain in Goldfinger (1964) due to his chilling performance in this.

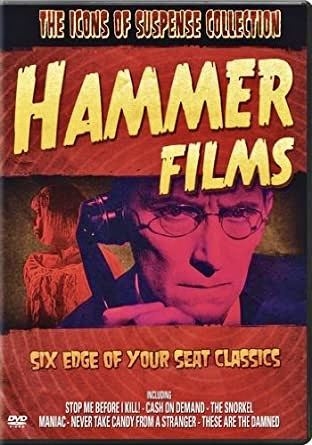

Never Take Candy from a Stranger was a difficult film to see for years but it finally emerged on DVD in April 2010 thanks to Sony Pictures Home Entertainment which included it in the box set, The Icons of Suspense Collection, which is a must-have for any Hammer aficionado. In fact, The Icons of Suspense Collection would be worth buying just for These Are the Damned (1961, aka The Damned) alone – Joseph Losey’s remarkably eclectic and fascinating mash-up of political sci-fi and juvenile delinquency drama starring MacDonald Carey, Shirley Anne Field, Oliver Reed, Viveca Lindfors and Alexander Knox. It has a great music score by James Bernard too with that catchy pop tune that goes “Black leather, black leather, smash, smash, smash”). But there are other rarities here too such as Peter Cushing in the bank heist thriller Cash on Demand (1961), the bizarro murder mystery The Snorkel (1958), featuring one of the great B-movie opening sequences, Val Guest’s Stop Me Before I Kill! (1960, aka The Full Treatment) with Ronald Lewis and Diane Cilento, and Maniac (1963), one of the better post-Psycho imitations with an appealing international cast that includes Nadia Gray (La Dolce Vita), Kerwin Mathews, Donald Houston and Liliane Brousse.

In March 2018 Sony finally released Never Take Candy from a Stranger on Blu-ray and paired it with Scream of Fear aka Taste of Fear (1961), one of Hammer’s finest suspense thrillers of the sixties. It stars Susan Strasberg as a wheelchair-bound woman who returns to her late father’s estate and is soon driven into a state of hysteria by unexplained occurances. It makes for a superb double feature.

Other links of interest:

http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/1350615/index.html

https://directors.uk.com/news/remembering-cyril-frankel

https://ascmag.com/articles/cinematic-glory-freddie-francis-bsc

Birth of Actor Niall MacGinnis