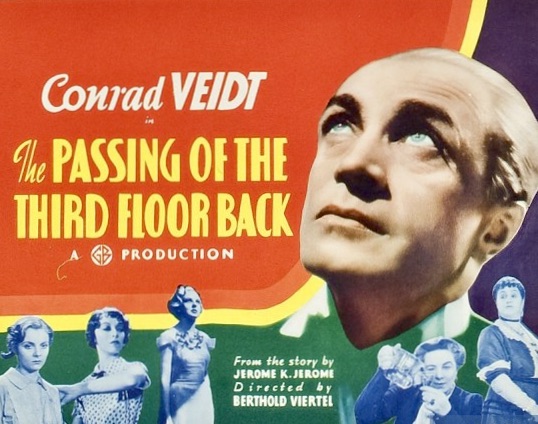

A mysterious stranger arrives at a boarding house in London and inquires about the advertised room to let. The landlady has some reservations about him but his good manners, personal charisma and willingness to pay his rent in advance convinces her he will be a respectable lodger. How many times have we seen movies that open with the same scenario where the new boarder turns out to be a suspicious character and possibly mentally unhinged? Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1927), Man in the Attic (1953), Roman Polanski’s The Tenant (1976) and The Minus Man (1999) are some of the more famous examples of this. The 1935 British film, The Passing of the Third Floor Back, however, gives us a protagonist who could be some kind of savior in disguise, a spiritual being who has come to help the unhappy and misanthropic boarders. Is he an angel, a Christ figure or maybe a figment of someone’s imagination?

Continue readingTag Archives: Alfred Hitchcock

The Dark Side of Robert Young

When most baby boomers think of actor Robert Young, they probably recall his popular TV medical series Marcus Welby, M.D. (1969-1976) where he was the epitome of the kind, compassionate doctor or they remember Jim Anderson, the perfect dad in the all-American family sitcom Father Knows Best (1954-1960). He was also typecast as “Mr. Nice Guy” in most of his Hollywood films, playing cheerful romantic leads or the leading man’s best friend or some other debonair, noble or well-intentioned character who rarely made a strong impression compared to more assertive male leads like Clark Gable, Gary Cooper or Spencer Tracy. But there were several occasions when Young discarded his good guy image by playing shadowy characters, outright villains, or damaged human beings. Among these atypical casting choices, Young is most memorable in Alfred Hitchcock’s Secret Agent (1936) as an undercover spy, a budding fascist in The Mortal Storm (1940), a shellshocked and physically maimed war veteran in The Enchanted Cottage (1945), a complete cad and accused murderer in the underrated film noir They Won’t Believe Me (1947), directed by Irving Pichel, and an architect who is suspected of being a dangerous criminal in The Second Woman (1950).

Continue readingHenri-Georges Clouzot’s Le Corbeau

In a small village in rural France, an anonymous writer sends a series of poison-pen letters to selected residents. Signed with the mysterious name of “Le Corbeau”, the letters accuse the new physician in town, Dr. Remy Germain (Pierre Fresnay), of adultery and performing abortions. While the townspeople are scandalized by this information, it soon becomes apparent that Dr. Germain is not the only target of this vicious character assassination and that other respected members of the community will soon be victimized, their most shameful secrets exposed to all by “The Raven.” Soon, the villagers begin turning on each other, creating an atmosphere of increasing paranoia and mistrust that culminates in murder, suicide and an angry mob scene. There might not be a more misanthropic view of humanity than Le Corbeau (aka The Raven, 1943), directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot (The Wages of Fear, 1953), but the movie is not only a dark, brilliantly conceived melodrama which unfolds like a suspense thriller but a cautionary character study of how fear of others brings out the worst in everyone.

Continue readingThe Old Dark House of Cyrus West

Some believe “Old Dark House” thrillers began with J.B. Priestley’s 1927 novel Benighted, which was adapted for the screen by James Whale as The Old Dark House in 1932. The reality is that the template had already been created by Mary Roberts Rinehart in her 1908 novel The Circular Staircase, which she reworked into a highly successful 1920 Broadway production entitled The Bat with playwright Avery Hopwood. Author and actor John Willard also had a Broadway smash hit with his 1922 play The Cat and the Canary, which shared a number of familiar horror/mystery elements with Rinehart’s creation, most significantly the gloomy mansion in an isolated setting with a menacing character prowling the corridors.

Continue readingPinko Paranoia

Only two years after WW2 officially ended on September 2, 1945, relations between the United States and the USSR cooled and became frosty, ushering in The Cold War era, which lasted until the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991. Hollywood was quick to capitalize on this disturbing new reality by producing and releasing a string of anti-communist dramas, adventures and spy thrillers, many of them grade A productions with major stars from the top studios. One of the earliest releases was The Iron Curtain (1948) from 20th-Century-Fox, which was directed by William A. Wellman and reunited Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney from Laura in a true life story about a Soviet defector in Canada. Many others followed such as The Red Danube (1949) and Conspirator (1949) from MGM, Diplomatic Courier (1952) with Tyrone Power battling Soviet agents in post-war Europe and Leo McCarey’s infamous red scare melodrama, My Son John (1952). Even John Wayne got on the patriotic bandwagon and sounded off against the commies in Big Jim McLain (1952) from United Artists, Blood Alley (1955) from Warner Brothers, and Jet Pilot (1957) from RKO. All of these, however, were high profile releases compared to 5 Steps to Danger (1957), a modest but highly entertaining indie feature from Grand Productions (distributed by United Artists), which teamed up Sterling Hayden and Ruth Roman.

Continue readingThe Haunted Cornea

When Nobuhiko Obayashi’s Hausu (English title: House) opened in Japan in 1977, it proved to be a surprise hit with audiences but not Japanese film critics and it didn’t attract any attention in the U.S. until it was rediscovered in 2009 as possibly the weirdest WFT cult movie since El Topo (1970), Eraserhead (1977) or Repo Man (1984). Originally intended for teenagers, particularly girls, House pits a bunch of young female schoolgirls against a demonic entity and the result is a frenzy of nightmarish images including flying decapitated heads, a cannibalistic piano, a satanic cat, and laughing watermelons to name a few. Obayashi’s subsequent film, Hitomi no naka no houmonsha (English title: The Visitor in the Eye, 1977) isn’t nearly as wild and raucous but it shares the same demented fairy tale ambiance of House and was overshadowed by its predecessor.

Continue readingThorold Dickinson’s Secret People

Though little known in the U.S. today except by movie buffs, Thorold Dickinson is an important figure in the development of the British film industry. A screenwriter, editor, director and producer, Dickinson wore many hats and exerted considerable influence in his various positions over the years as Coordinator of the Army Kinematograph Service’s film unit, Professor of Film at the Slade School of Fine Art and Chief of Film Services at UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). In addition to collaborating with other British filmmakers on their work and co-directing several features, he rose to prominence on the basis of a small but impressive filmography. Among them were the commercial hits, Gaslight (1940), remade in 1944 in Hollywood with Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer, and The Queen of Spades (1949), an adaptation of the Alexander Pushkin short story which is considered possibly the best of its many film versions. His skill as a documentarian was equally renowned and The Next of Kin, a military training film he made for the War Office in 1940, was so effective it was given a theatrical release. Men of Two Worlds (1946), a semi-documentary collaboration between the Ministry of Information and the Colonial Office, was co-scripted with novelist Joyce Cary (The Horse’s Mouth, 1958) and focused on the problem and treatment of sleeping sickness in African tribes. Yet, the most ambitious film of Dickinson’s career – and the one that almost ended it was Secret People (1952), which was an examination of the terrorist mindset and years ahead of its time.

Continue readingFrom Socialite to Streetwalker

There have been some terrific Pre-Code dramas that were set in the Depression and were actually playing in movie theaters at the time but, for obvious reasons, were not box office hits because audiences wanted escapism, not a reminder of their problems. Still, several of these social problem dramas like William Wellman’s Heroes for Sale (1933) and Wild Boys of the Road (1933) were championed by film critics and today provide an invaluable window into that era. Faithless (1932), directed by Harry Beaumont (Dance, Fools, Dance) and based on the novel Tinfoil by Mildred Cram, also belongs in that category, even if it was poorly received at the time, and deserves a revival for its unusual mixture of soap opera, social issues and adult themes like prostitution.

Continue readingEast German Film Rarities

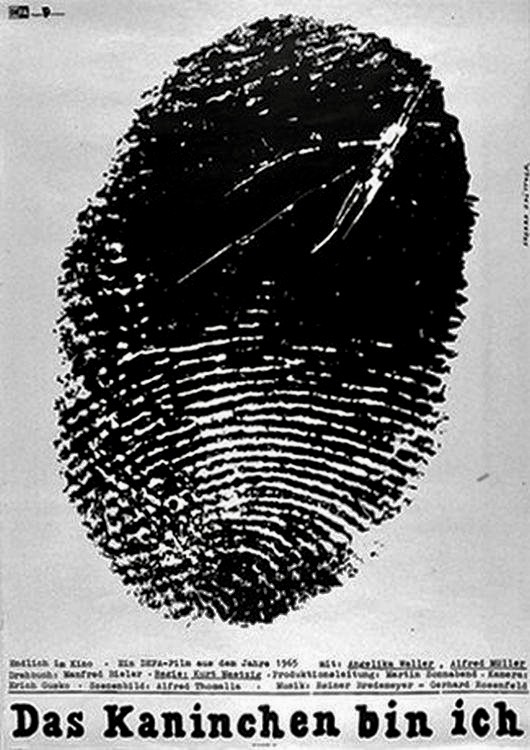

While most hardcore film buffs are well versed in the movies of Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, F.W. Murnau and their latter compatriots Werner Herzog, R.W. Fassbinder, Wim Wenders and Volker Schlondorff, directors such as Kurt Maetzig, Joachim Kunert and Gerhard Klein are completely unknown or unfamiliar to Western audiences for an obvious reason. They worked for DEFA (Deutsche Film Aktiengesellschaft), the nationalized film industry of East Germany, and as a result, very few of their movies were distributed outside of socialist countries during the Cold War Era when DEFA was in its prime. A rare exception was Kurt Maetzig’s Der Schweigende Stern aka The Silent Star, a science fiction adventure which was released in the U.S. in an edited, English dubbed version as First Spaceship on Venus in 1962. Much more complex and thematically intriguing is Maetzig’s Das Kaninchen Bin (English title: The Rabbit is Me, 1965) along with Joachim Kunert’s Das Zweite Gleis (English title: The Second Track, 1962) and Gerhard Klein’s Die Fall Gleiwitz (English title: The Gleiwitz Case, 1961).

Continue readingSecond Sight

The gift of clairvoyance and the ability to predict the future is a plot device that has been well mined in the cinema from It Happened Tomorrow (1944) to Nightmare Alley (1947) to The Night My Number Came Up (1955). But one of the earliest and most intriguing presentations of this phenomenon can be found in the rarely seen 1934 release, The Clairvoyant (aka The Evil Mind). Made at an early stage in Claude Rains’ career when he was still accepting film work in both Hollywood and England and was not yet a contract player at Warner Bros., The Clairvoyant provides an excellent showcase for the actor as Maximus, the mind reader.

Continue reading