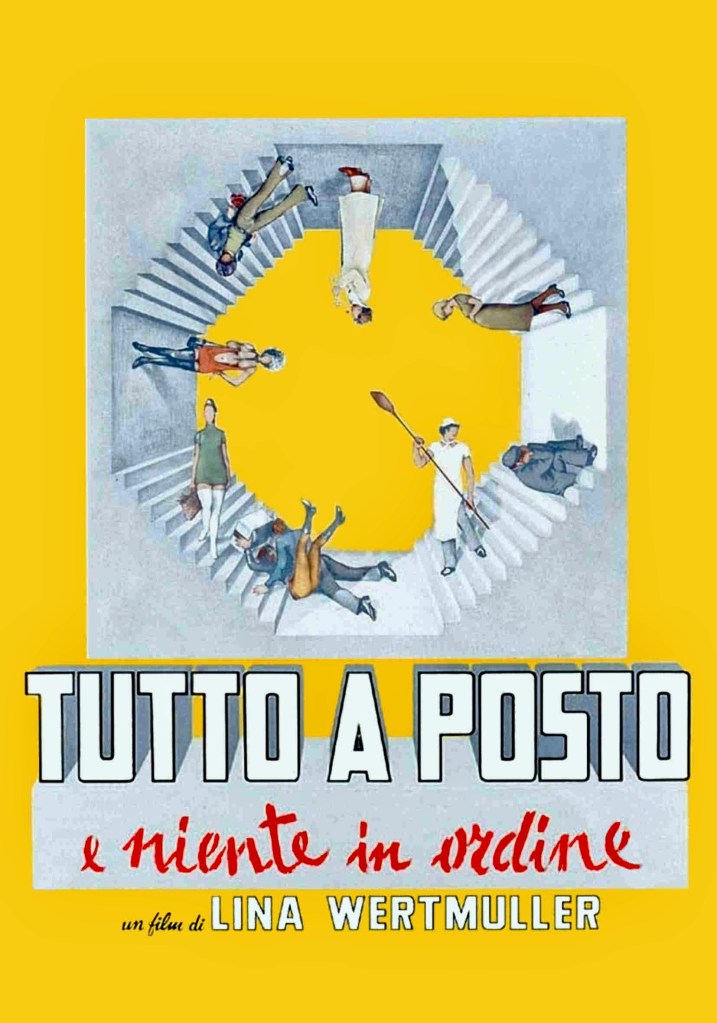

Gigi and Carletto are two naïve country bumpkins who, like many others from rural Italy and southern regions like Sicily, have come to the northern city of Milan to seek their fortunes. They soon fall in with other recent arrivals to the city seeking work and eventually set up a communal living situation in an abandoned apartment with others. Both men have big dreams and expectations but the reality is quite different from what they imagined and they fall prey to the city’s corrupting influences. It is a familiar scenario that you have probably seen in numerous other movies but director Lina Wertmuller gives it her own unique spin in Tutto a posto e niente in ordine (English title: All Screwed Up, 1974), an exuberant, gleefully crude satire that uses broad comedy and eccentric characters to magnify the myriad problems of Italy during the early 70s. This is her idiosyncratic contribution to Commedia all’italiana, a genre of comedic social commentary first created by Mario Monicelli and Pietro Germi in the late fifties/early sixties with such films as Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958) and Divorce Italian Style (1961), satires where serious themes like poverty, unemployment, marital woes and economic hardships are treated in a lighthearted style.

Continue readingTag Archives: Vincent Canby

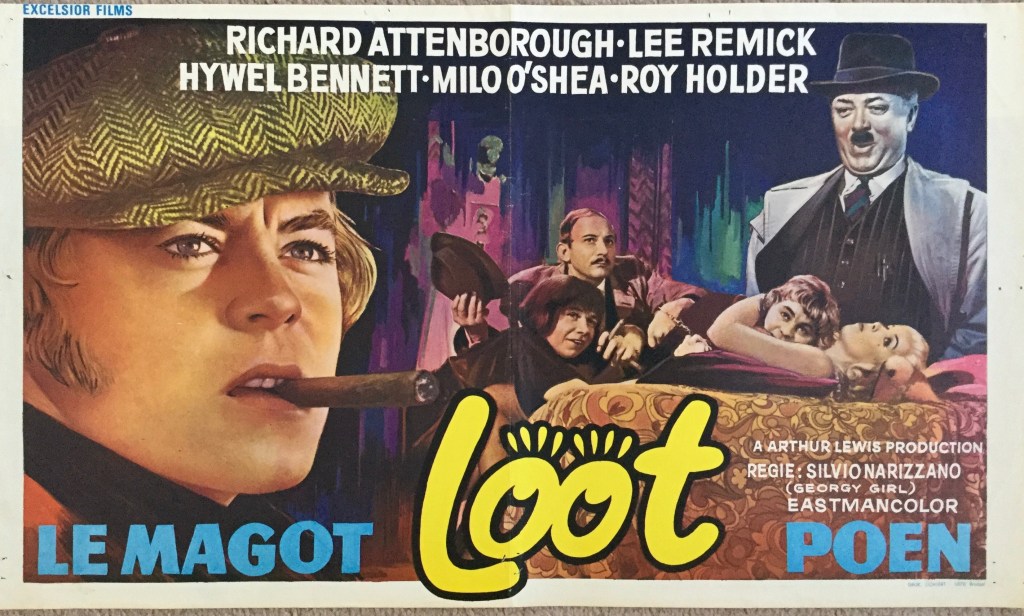

Joe Orton’s Impolite Farce

Black comedy may be an acquired taste but it still takes a clever and wickedly funny practitioner of the form to pull it off and Joe Orton was one of the best. The enfant terrible of British theatre in the sixties, Orton’s promising career was cut short in 1967 when he was bludgeoned to death by his lover Kenneth Halliwell. This final curtain, along with the events that led up to it, were covered in detail in John Lahr’s excellent biography of the acclaimed playwright Prick Up Your Ears, which was adapted to the screen in 1987 by Stephen Frears from a screenplay by Alan Bennett and featured Gary Oldman as Joe Orton. While Frears’ biopic was a fascinating character study, it didn’t really delve into the nuts and bolts of Orton’s craft or why such stages farces as Entertaining Mr. Sloane and What the Butler Saw became such popular and scandalous causes celebres among theatre critics and playgoers. The only thing that can really do justice to Orton’s particular brand of outrageous comedy and satire is a first rate production of one of his plays. A film adaptation would be much trickier because so much of Orton’s humor involves language – its proper and improper usage, double entendres, slang, class accents and other specifics. Of course, that didn’t stop filmmakers from attempting to bring his work to the screen and Loot became the second Orton play to receive the big screen treatment in 1970 (Entertaining Mr. Sloane, another Orton play adapted to film, had been released earlier in 1970).

Continue readingRupert Pupkin’s Stand-Up Act

Some movies are prescient or ahead of their time but audiences and film critics often don’t notice until many years after the original release. Sidney Lumet’s Network (1976), written by Paddy Chayefsky, is one example, but so is The King of Comedy (1983), which unlike Network, was a major box office bomb for director Martin Scorsese and received mixed reviews from the critics. Yet, it seems more relevant than ever about the cult of celebrity and the public’s obsession with the rich and famous. Although The King of Comedy was promoted as a comedy, some critics and moviegoers found the film too dark and disturbing and felt Rupert Pupkin, the title character, was just as delusional and dangerous in his own way as Travis Bickle, the anti-hero of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976).

Continue readingWho Has the Last Laugh?

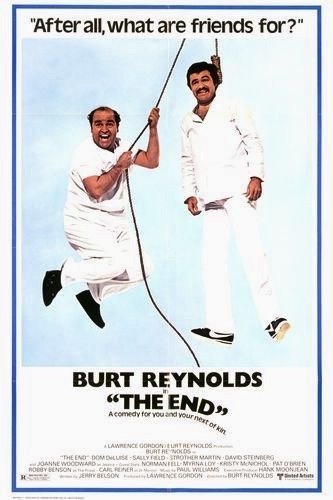

By 1978 Burt Reynolds was approaching the peak of his popularity which would begin to taper off in the mid-eighties as he approached the age of 50. He had just completed two huge box office hits, Smokey and the Bandit and Semi-Tough (both 1977) and was in a position to choose and develop any project he fancied. But instead of rushing into a sequel to Smokey and the Bandit or some other big budget vehicle that exploited his good ole boy blend of machismo, charm and sex appeal, Reynolds chose to make a risky, offbeat black comedy about a man dying of a terminal condition who contemplates suicide as a solution to a slow, agonizing death. In addition, the popular leading man would direct and star in it and cast his girlfriend at the time Sally Field in a prominent role. Released as The End in 1978, the film was not what moviegoers or critics expected from Reynolds or even wanted.

Continue readingThe Outsider and His Art

The image of the starving artist, living in poverty and misunderstood by everyone during his own lifetime, is an age-old cliché but is often based on true accounts. One of the more famous examples is Niko Pirosmanashvili, a self-taught artist from Mirzaani, Georgia, who was not motivated by money or fame but often used his paintings as barter for bed and board. He was born in 1862 and died in Tbilisi, Georgia in 1918 of alcoholism and starvation but his work is now considered part of the Russian avant-garde movement which flourished between 1890 and 1930. Pirosmani, the 1969 film biography by Russian director Giorgi Shengelaia, is an attempt to capture the spirit of the artist’s work without resorting to the usual biopic structure of dramatizing key events or providing any psychological insight into the subject. Instead, Shengelaia presents Pirosmani’s life as a string of episodes that are closer in style to an ethnographic documentary while duplicating some of the artist’s most famous paintings as part of the narrative landscape.

Continue readingHomeward Bound

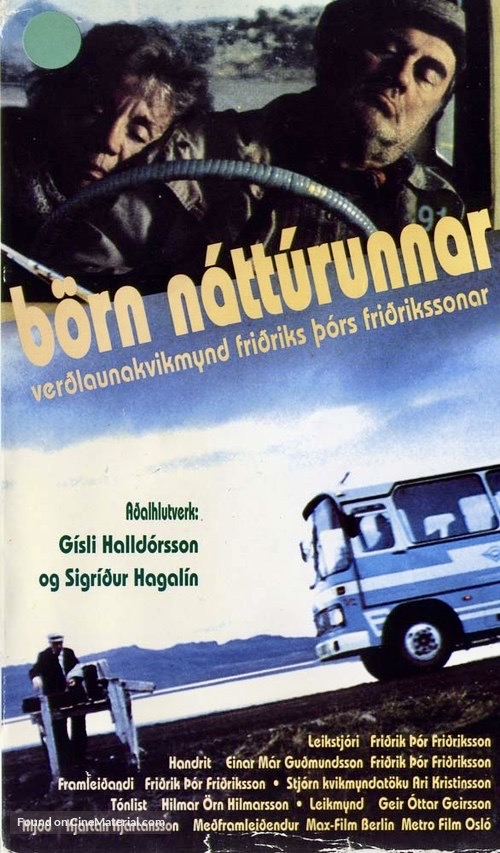

Films about aging and the elderly are not that prevalent in Hollywood’s yearly production schedule of new films for obvious reasons. It is not a subject that most moviegoers seeking escapism, especially younger viewers, want to contemplate. It is also a risky commercial proposition unless the film is a heartwarming drama with broad appeal (Driving Miss Daisy, 1989) or a feel-good comedy like Harold and Maude (1970), which was a box office flop on its initial release before it went on to become a profitable cult hit. Of course, some of the undisputed masterpieces of 20th century cinema have focused on senior citizens like Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D (1952), Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story (1953), and Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957) but these are not mass appeal attractions but the favorites of a niche art house audience. Fridrik Thor Fridriksson’s Children of Paradise aka Born Natturunnar (1991) is certainly a film that belongs in this latter grouping but is distinctly different in tone, combining social realism with deadpan humor and a touch of magical realism.

Continue readingAboriginal Prophecies from Down Under

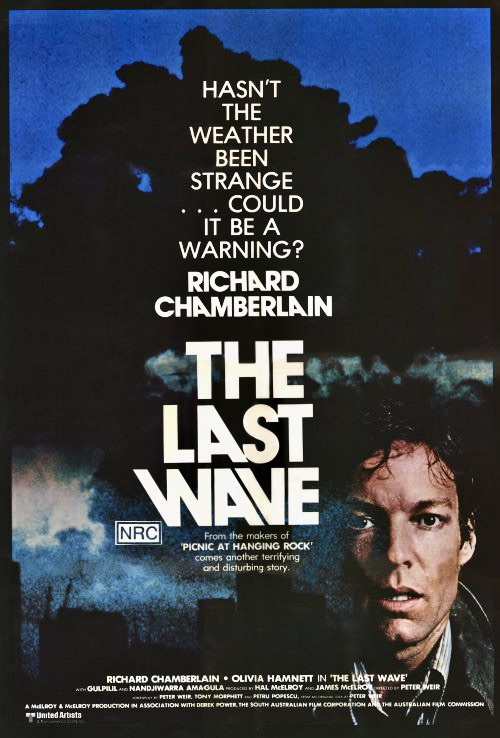

The rational versus the irrational always creates compelling conflicts in the best kind of fantasy/horror films where scientists and/or investigators are faced with trying to understand or explain supernatural events or mysteries of the occult. A denial of the paranormal fueled the chilling storyline of Jacques Tourneur’s Curse of the Demon (1957, released in the U.K. as Night of the Demon). A similar tone of skepticism is under attack in The Last Wave (1977), one of the rare Australian films to delve into Aboriginal mythology and superstitions but also one that addresses the environment on an apocalyptic level.

Continue readingThrough the Eyes of a Child

Roberto Rossellini’s Roma, Citta Aperta (Rome, Open City, 1945) is generally acknowledged as the film that ushered in the neorealism movement and set the tone and style for the postwar Italian films that followed. But the roots of neorealism can be traced back to Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione (1943) and Vittorio De Sica’s The Children Are Watching Us (1944, I bambini ci guardano), both of which were filmed in 1942 but encountered distribution problems upon their release in the fall of 1942 when the war finally came to Italy and the bombings began. Ossessione was also the victim of Fascist censorship which reduced the film to less than half of its original running time and for years it was denied distribution in the U.S. due to an infringement of copyright (it was an uncredited adaptation of the James M. Cain novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice). The Children Are Watching Us didn’t fare any better during its limited release and for years it was a difficult film to see in its original form, even in its own country.

Continue readingIdentity Disintegration

What would happen if you lost the face you recognize as your own and had to replace it with a new one? Would you have an identity crisis or simply become a different person? Japanese director Hiroshi Teshigahara ponders this unusual dilemma in The Face of Another (1966, Japanese title: Tanin no kao). Continue reading

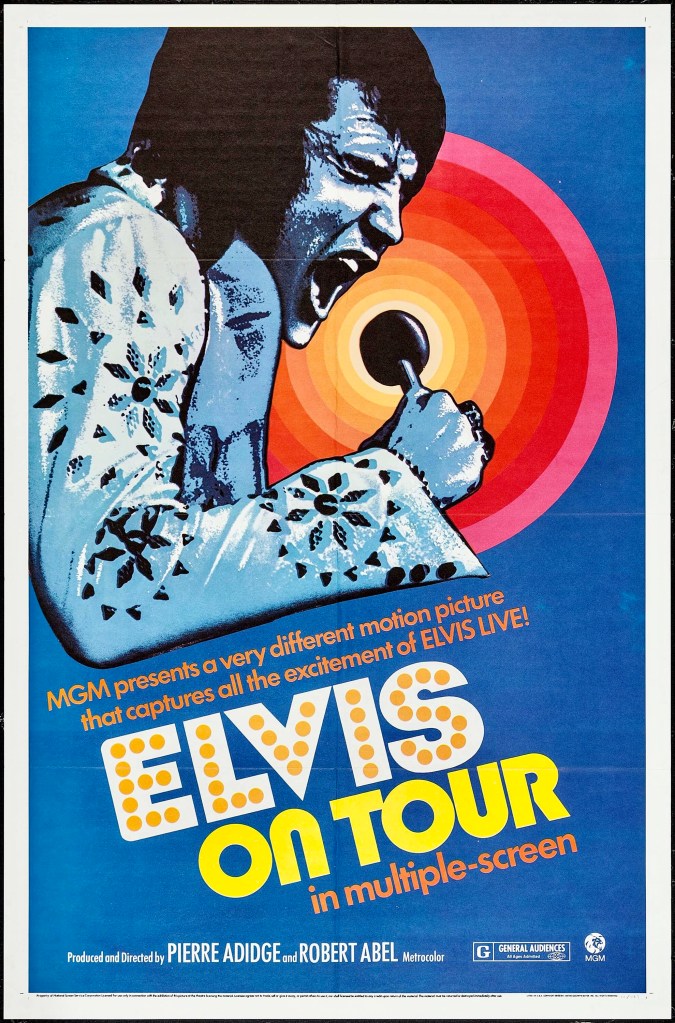

Elvis is Leaving the Building

During his lifetime, Elvis Presley made 31 feature films, two theatrical documentaries and numerous TV specials. What is rather surprising is the fact that Hollywood never showcased Elvis as a live performer or in a concert film until the end of his career. How much of that was due to his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, is debatable but Elvis on Tour (1972) is regarded as the last official Elvis movie that was distributed to theaters.