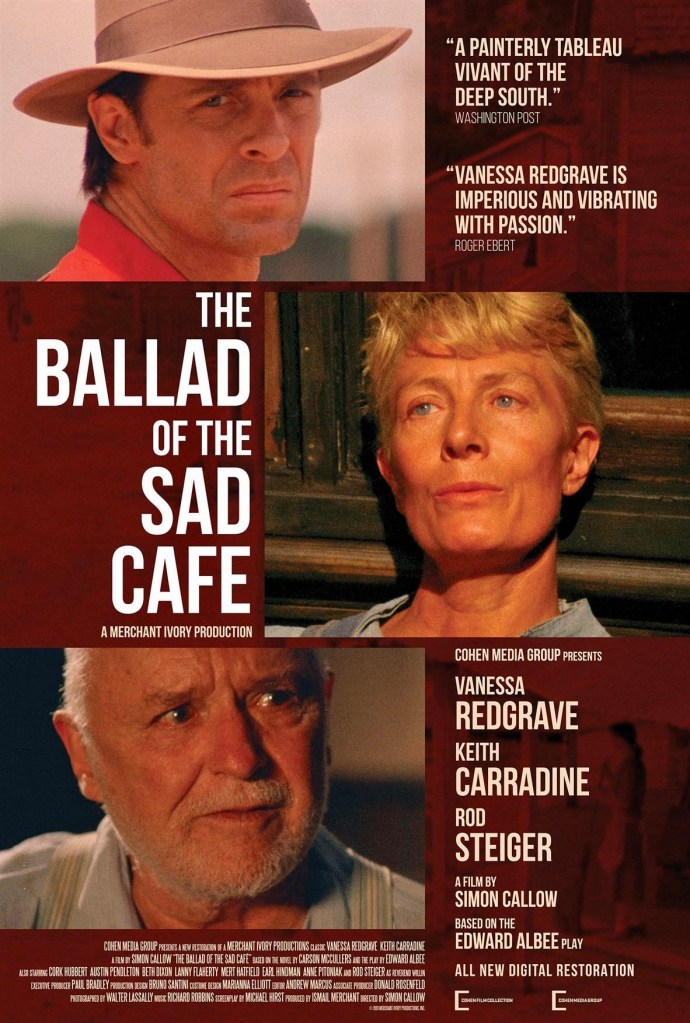

When people talk about Southern Gothic literature, they are usually referring to writers such as William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, Flannery O’Connor, Erskine Caldwell and Carson McCullers and novels featuring marginalized characters suffering from loneliness, madness or despair in distinct Southern settings. A typical example would be McCullers’s second novel Reflections in a Golden Eye, published in 1941, which is set on a Southern army base in the 1930s and depicts various characters who identify with voyeurism, self-mutilation, repressed gay desire and murder. On the other hand, her 1951 novella The Ballad of the Sad Café has some Southern Gothic elements but is actually much closer to a bizarre folk tale handed down from some primeval culture with its grand passions and Greek tragedy stylings. It would seem the most unlikely candidate among her novels for a film adaptation and yet it was turned into a movie in 1991 by actor and celebrated author Simon Callow. Critics were divided over its success as cinema but for those willing to suspend their disbelief over the larger-than-life characters and storyline, The Ballad of the Sad Café is an admirable attempt to capture the heart and soul of McCullers’s original work. Callow finds a nice balance between theatricality and naturalism, the grotesque and the poignant, all supported in part by strong performances, especially Vanessa Redgrave in the central role.

Continue readingTag Archives: Vanessa Redgrave

The Spider and the Fly

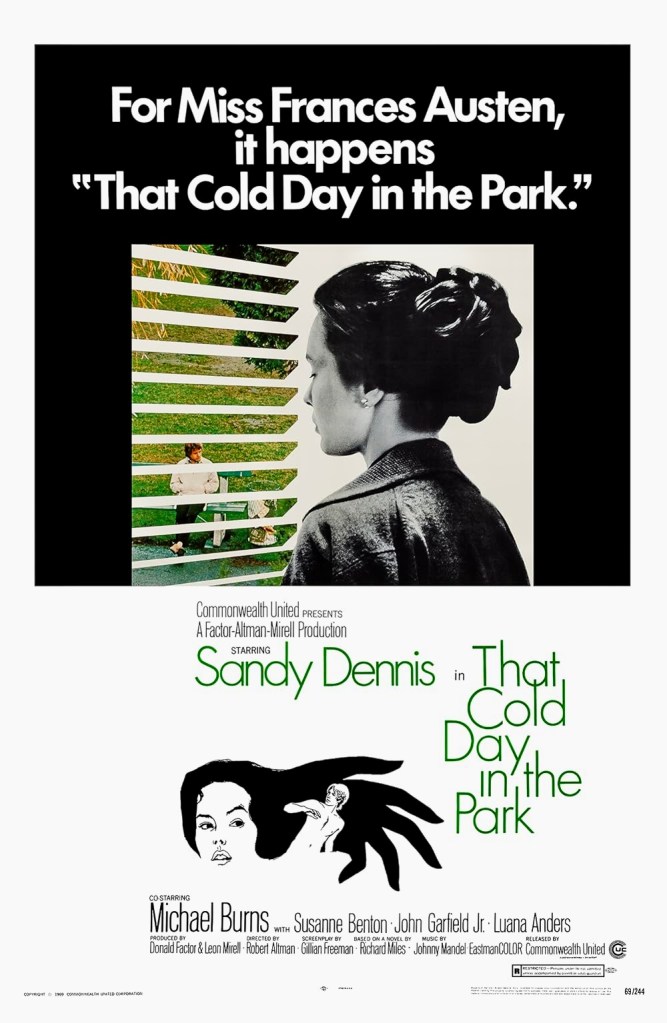

Most film critics and movie lovers point to Nashville (1975) as Robert Altman’s masterpiece, although I’ve always been partial to his unique spin on the Western, McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971). I also admire an earlier film that he directed that was conspicuously absent or missing from his filmography in most of the obituaries on the director after he died. That Cold Day in the Park was made between Countdown (1967) and M*A*S*H* (1970) in 1969 and was based on a novel by Richard Miles. The screenplay was by British screenwriter Gillian Freeman, who had written the novel and film adaptation of The Leather Boys (1964), Sidney J. Furie’s drama about a troubled working class marriage and the husband’s friendship with a closeted gay biker.

A gender twist on John Fowles’s The Collector, That Cold Day in the Park stars Sandy Dennis as Frances Austen, a lonely spinster whose apartment overlooks a park in Vancouver. One wet, wintry day she spots a young man on a park bench who appears to be homeless. She invites him into her home to get warm but ends up encouraging him to stay. The fact that the stranger (Michael Burns) pretends to be mute only adds to the ensuing strangeness. His little joke backfires, however, when he arouses Dennis’s long-suppressed sexual feelings and becomes a prisoner in her apartment.

Continue readingSwinging Down the Street So Fancy Free

A frumpy woman in her early twenties dreams of being loved but despite her continual attempts to have a romance finds herself observing life from the sidelines, barely noticed by those around her. Reduced to a one sentence description, Georgy Girl (1966) sounds dreary and depressing but on-screen this tale of a desperately lonely woman unfolds as a madcap, often irreverent farce which at times is cruelly indifferent to the sad-sack characters it parades before us. This is a film where tone is everything and Georgy Girl, directed by Silvio Narizzano, is distinctively different in this respect, standing out from countless other cinematic tearjerkers about ugly ducklings and lonely spinsters. The film also captures London at the height of the Swingin’ Sixties when everything seemed like a put-on or a come-on.

Continue readingA Suitable Case for Treatment

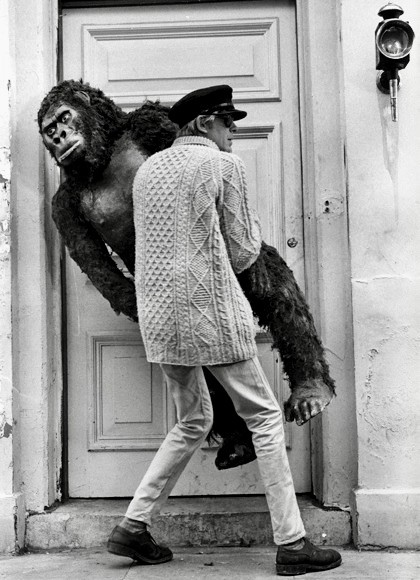

Is mental illness a laughing matter? When it comes to cinematic treatments, it all depends on the filmmaker’s approach and this was an issue that divided critics and audiences over Morgan! (1966, released in the U.K. as Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment). Whether embraced as a wild, eccentric anti-establishment farce or derided as a schizophrenic mess that can’t decide whether it’s a comedy or a tragedy, Morgan!, remains a polarizing film even today; there is no middle ground here. Most people either love it or hate it.

Continue readingElio Petri’s Portrait of the Artist as Mental Patient

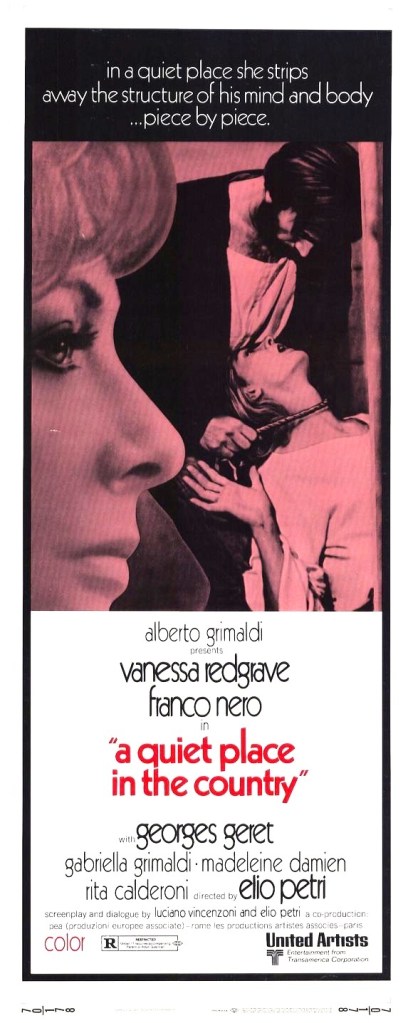

Italian director Elio Petri is probably best known for Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970), which won the Oscar for Best Screenplay (by Petri and Ugo Pirro) in 1972. Yet, most of his other work, with the possible exception of the cult sci-fi satire The 10th Victim (1965), remains overlooked or forgotten when film historians write about the great Italian directors of the sixties and seventies. And 1968’s A Quiet Place in the Country (Un Tranquillo Posto di Campagna) is easily one of his most intriguing and visually compelling films.

Italian director Elio Petri is probably best known for Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970), which won the Oscar for Best Screenplay (by Petri and Ugo Pirro) in 1972. Yet, most of his other work, with the possible exception of the cult sci-fi satire The 10th Victim (1965), remains overlooked or forgotten when film historians write about the great Italian directors of the sixties and seventies. And 1968’s A Quiet Place in the Country (Un Tranquillo Posto di Campagna) is easily one of his most intriguing and visually compelling films.

Any Port in a Storm

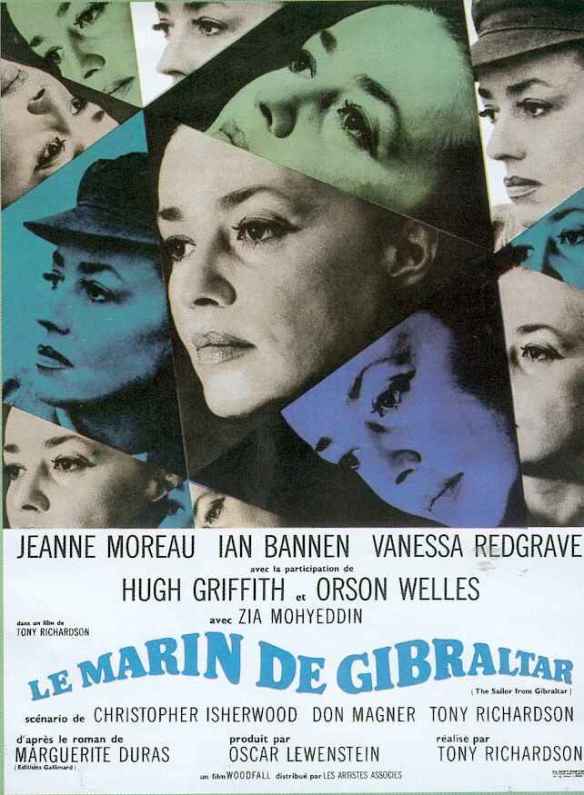

Along with his film adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark (1969), Tony Richardson’s The Sailor from Gibraltar (1967) is probably the most obscure and rarely seen film from the director’s middle period, a time when he was floundering and unable to match the earlier critical and commercial success of his 1963 Tom Jones adaptation. There are many reasons for that, of course, and Richardson would probably admit it was one of his biggest disasters, if not the biggest. It also wasn’t intended for the average moviegoer and was much more attuned to art house cinema patrons with its enigmatic story based on the novel Le marin de Gibraltar by Marguerite Duras, whose screenplay for Hiroshima, Mon Amour received an Oscar® nomination in 1961 (even though the film was released in 1959). To date, The Sailor from Gibraltar is still missing in action with no legal DVD or Blu-Ray release available. Continue reading

Along with his film adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark (1969), Tony Richardson’s The Sailor from Gibraltar (1967) is probably the most obscure and rarely seen film from the director’s middle period, a time when he was floundering and unable to match the earlier critical and commercial success of his 1963 Tom Jones adaptation. There are many reasons for that, of course, and Richardson would probably admit it was one of his biggest disasters, if not the biggest. It also wasn’t intended for the average moviegoer and was much more attuned to art house cinema patrons with its enigmatic story based on the novel Le marin de Gibraltar by Marguerite Duras, whose screenplay for Hiroshima, Mon Amour received an Oscar® nomination in 1961 (even though the film was released in 1959). To date, The Sailor from Gibraltar is still missing in action with no legal DVD or Blu-Ray release available. Continue reading