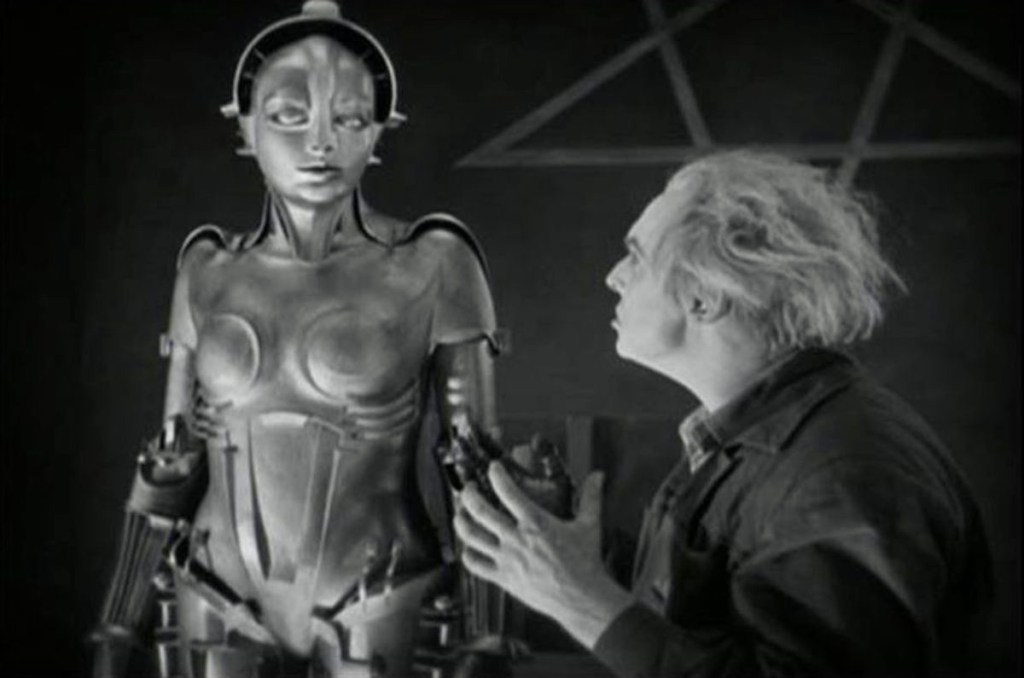

When I hear the word robot, I immediately think of Robby, the delightful and super intelligent creation of Dr. Morbius in Forbidden Planet (1956), one of the landmark sci-fi movies of the fifties. His barrel-shaped torso and high-tech design were so popular that he inspired countless toy collectibles for kids but he was a benign example of the form. For the most part, robots in science fiction films are generally viewed as a threat (see 1954’s Target Earth, 1957’s Kronos or 1958’s The Colossus of New York for examples). That was certainly the case in one of the first and most famous depictions of a robot – Fritz Lang’s silent sci-fi masterpiece, Metropolis (1927). Designed as a doppelganger for Maria, a revered female leader of factory workers, the false Maria preaches revolution to the working class, resulting in the sort of chaos that threatens to topple civilization (The False Maria’s robotic metal frame is disguised beneath her human façade).

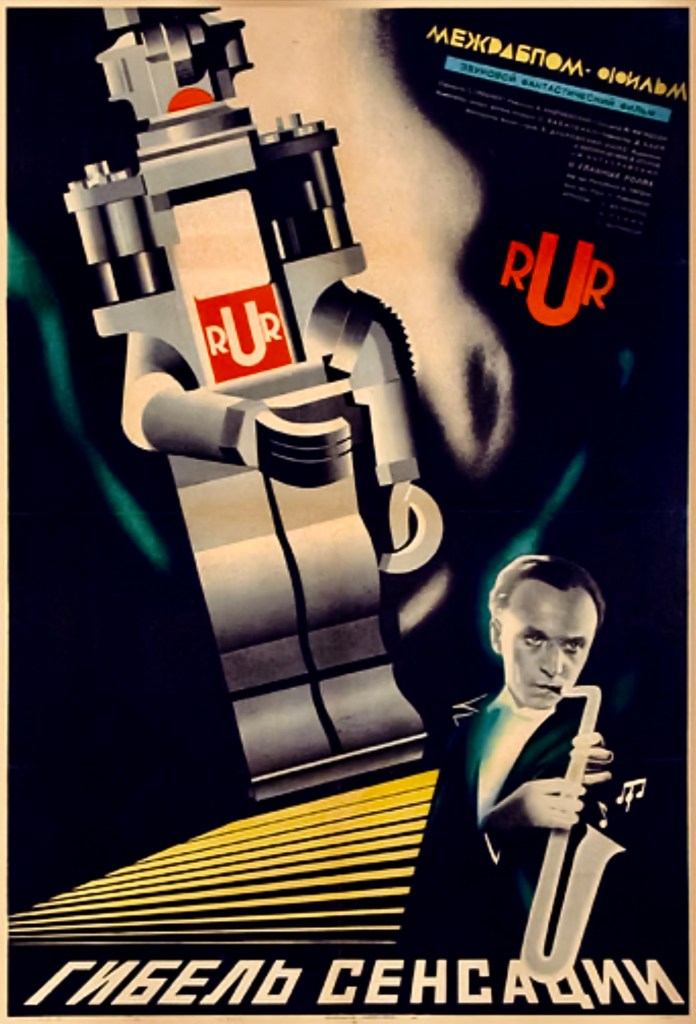

Eight years later, robots were again viewed as a danger to the human race in the Russian film, Gibel Sensatsii (English title: Loss of Feeling aka Loss of Sensation aka Robots of Ripl, 1935) although these looked more like early prototypes of the walking oil can-shaped automatons seen in later serials like The Phantom Empire (1936) and The Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940).

Continue reading