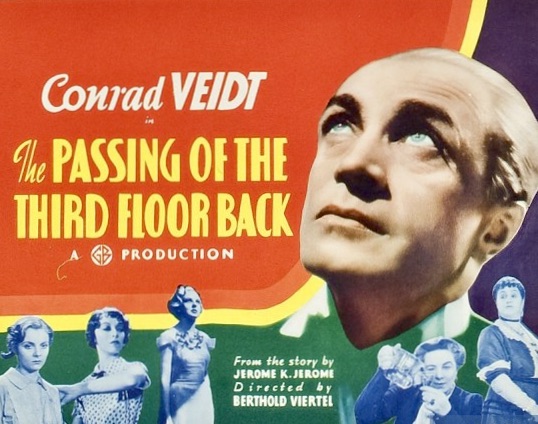

A mysterious stranger arrives at a boarding house in London and inquires about the advertised room to let. The landlady has some reservations about him but his good manners, personal charisma and willingness to pay his rent in advance convinces her he will be a respectable lodger. How many times have we seen movies that open with the same scenario where the new boarder turns out to be a suspicious character and possibly mentally unhinged? Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1927), Man in the Attic (1953), Roman Polanski’s The Tenant (1976) and The Minus Man (1999) are some of the more famous examples of this. The 1935 British film, The Passing of the Third Floor Back, however, gives us a protagonist who could be some kind of savior in disguise, a spiritual being who has come to help the unhappy and misanthropic boarders. Is he an angel, a Christ figure or maybe a figment of someone’s imagination?

Continue readingTag Archives: Val Lewton

Pedro Costa’s O Sangre

Most film aficionados known that the Cinema Novo movement of the 1960s in Brazil was influenced by both Neorealism and New Wave filmmakers but became an identifiable style of its own. Portugal also had their own Cinema Novo movement in the sixties but it transitioned into a different aesthetic approach in the 1980s known as “The School of Reis,” named after Antonio Reis, a filmmaker and professor at the Lisbon Theater and Film School. Reis influenced a new generation of filmmakers that includes Manuela Viegas, Joaquim Sapinho, Joao Pedro Rodgrigues and Pedro Costa to name a few. Among this group Costa is probably the best known in the U.S. due to his work being exhibited at film festivals and art houses as well as a trilogy of his films known as Letters from Fontainhas being distributed on DVD and Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection. Less known is his 1989 debut feature, O Sangre aka Blood, which Michelle Carey of Senses of Cinema called, “Undoubtedly one of the most remarkable film debuts of the last 20 years.”

Continue readingM.R. James Times Two

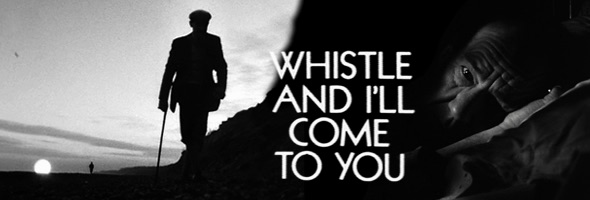

Montague Rhodes James, better known as M.R. James (1862-1936), was a celebrated author and medievalist scholar from the U.K. who is best known today for his many ghost stories. Horror film buffs in the U.S. were first exposed to his work when director Jacques Tourneur adapted his short story “Casting the Runes” for the 1957 film Curse of the Demon (it was titled Night of the Demon in the U.K.). To date, that still reminds the most famous M.R. James theatrical feature but that doesn’t mean the author’s work hasn’t been adapted in other memorable renditions, most of them as made-for-television productions from England. One of the most famous is James’s short story, “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad” from 1904, which has been filmed twice by the BBC, one in 1968 entitled Whistle and I’ll Come to You starring Michael Horden and a remake from 2010 with the same title that featured John Hurt.

Continue readingThe Vampire Moth

There are a number of classic Japanese horror/fantasy films from the fifties and sixties that genre fans in the U.S. have read about but never seen due to their unavailability on DVD or Blu-ray. In recent years a few of these have appeared in domestic release versions such as Nobuo Nakagawa’s 1960 allegorical masterpiece Jigoku (released by The Criterion Collection), in which a hit-and-run driver literally goes to hell, and the director’s 1968 supernatural tale Snake Woman’s Curse (released by Synapse Films). Many of the most famous examples of Japanese fantasy/horror from this period, however, still remain elusive for American viewers unless you own an all-region DVD/Blu-ray player and are willing to purchase import discs from Japan, often with no English subtitles. It is also true that many of these classic genre efforts were directed by Nakagawa who is famous for supernatural chillers as The Ghosts of Kasane Swamp (1957), Black Cat Mansion (1958), and The Ghost of Yotsuya (1959). But I have to admit that one of the director’s creepiest and least seen films is Kyuketsu-ga (English title: The Vampire Moth, 1956), which combines mystery thriller tropes with grotesque horror elements to achieve a delightfully macabre brew.

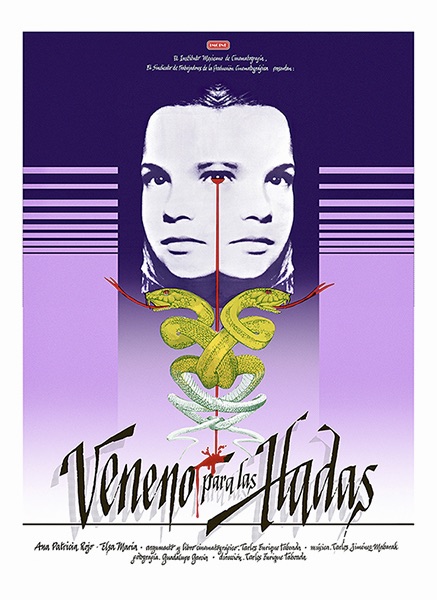

Carlos Enrique Taboada’s Poison for the Fairies

Most film historians point to a timeline between 1957 through 1967 as the Golden Age of Mexican horror cinema. This was a period that produced such iconic titles as El Vampiro (1957), The Black Pit of Dr. M (1959), The Brainiac (1962) and Dr. Satan (1966). The country’s film industry continued to make horror and fantasy films through the seventies and beyond, of course, but the majority of them tended to be cheaper productions in which masked wrestlers like Santo and Blue Demon battled a variety of monsters. A welcome exception to this popular but overworked formula are the horror films of Carlos Enrique Taboada, which were more subtle and suggestive in comparison like the atmospheric chillers Val Lewton produced for RKO Pictures in the forties. An outstanding example of Taboada’s original approach to the genre is Veneno para las hadas (English title: Poison for the Fairies, 1986), which is less of a supernatural thriller and more of an exploration of evil in the tradition of The Bad Seed (1956) and The Other (1972).

Continue readingBeware of Japanese Cats

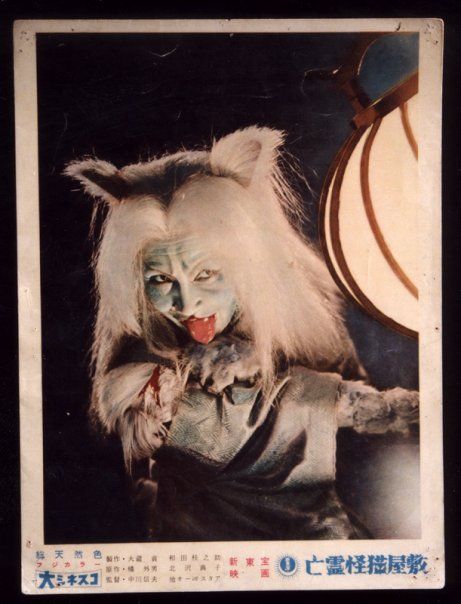

The avenging cat witch ghost is the star of Nobuo Nakagawa’s Black Cat Mansion aka Borei Kaibyo Yashiki (1958).

Every national cinema has their own homegrown subgenres and mythology when it comes to horror films and I think Japan has some of the most unique and bizarre creatures of all such as the hopping Umbrella ghost from Yokai hyaku monogatari (1968, aka The Hundred Monsters) or the rampaging stone idol of the Majin trilogy which began in 1966. Yet, in terms of eerie beauty and supernatural creepiness, I’m drawn to the bakeneko-mono stories from Japanese folklore with their shape-shifting cat demons and one of my favorites is Borei Kaibayo Yashiki (1958, aka Black Cat Mansion aka Mansion of the Ghost Cat). Continue reading

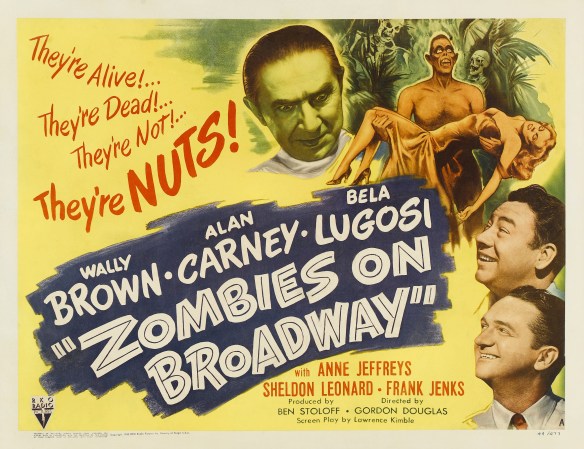

There’s No Business like Zombie Business……

In 1941, the unexpected success of Buck Privates – a whopping $10 million dollar B-movie blockbuster – officially launched the comedy team of Abbott and Costello who became Universal Studios’ most profitable film franchise for more than a decade (The duo made their debut in One Night in the Tropics (1940) in supporting roles but the musical comedy with top billed Allan Jones and Nancy Kelly was not a boxoffice hit). Naturally, it inspired other studios to follow suit but it wasn’t as easy as it looked. Case in point – Wally Brown and Alan Carney (no relation to Art Carney), two former nightclub comedians recruited by RKO for a series of low-budget farces beginning with The Adventures of a Rookie (1943), a blatant attempt to ape the formula of Buck Privates. For critics who thought the humor of Abbott and Costello was déclassé, Zombies on Broadway (194) was a further step down but perfect for eight year old boys who enjoyed the simple concept of two nitwits with one (Brown) assuming superiority over his dim bulb pal (Carney). Continue reading

In 1941, the unexpected success of Buck Privates – a whopping $10 million dollar B-movie blockbuster – officially launched the comedy team of Abbott and Costello who became Universal Studios’ most profitable film franchise for more than a decade (The duo made their debut in One Night in the Tropics (1940) in supporting roles but the musical comedy with top billed Allan Jones and Nancy Kelly was not a boxoffice hit). Naturally, it inspired other studios to follow suit but it wasn’t as easy as it looked. Case in point – Wally Brown and Alan Carney (no relation to Art Carney), two former nightclub comedians recruited by RKO for a series of low-budget farces beginning with The Adventures of a Rookie (1943), a blatant attempt to ape the formula of Buck Privates. For critics who thought the humor of Abbott and Costello was déclassé, Zombies on Broadway (194) was a further step down but perfect for eight year old boys who enjoyed the simple concept of two nitwits with one (Brown) assuming superiority over his dim bulb pal (Carney). Continue reading