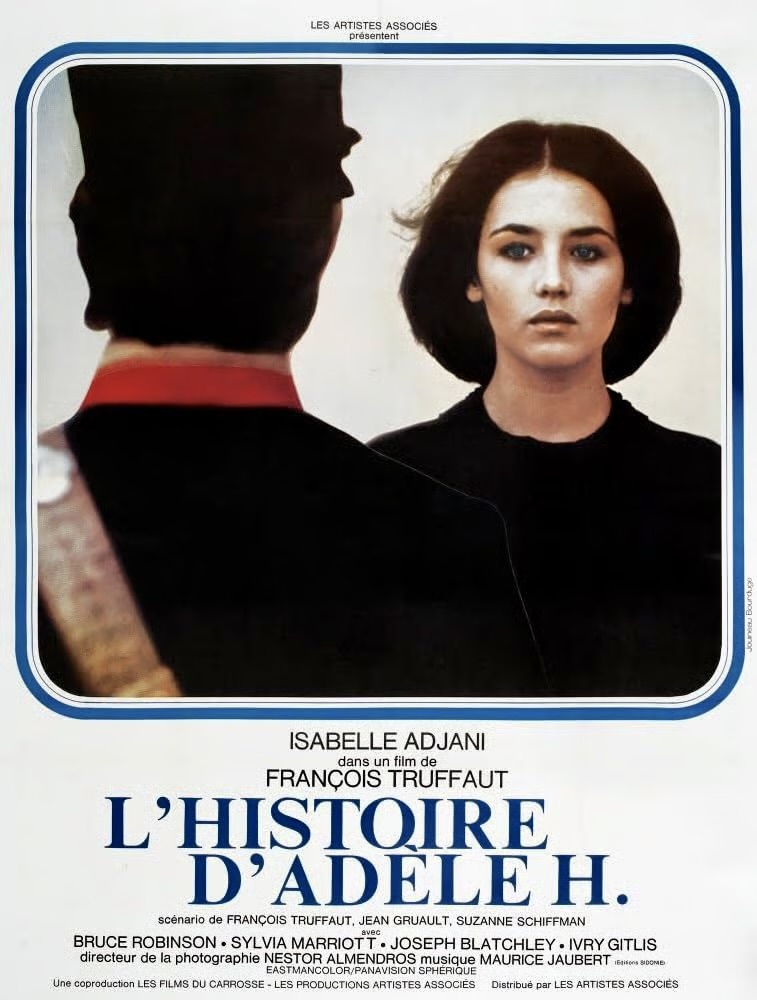

Francois Truffaut is one of those directors whose career peaked early with the phenomenal semi-autobiographical debut film The 400 Blows in 1959 at the dawn of the Nouvelle Vague and followed it with two more masterworks – Shoot the Piano Player (1960) and Jules and Jim (1962). The next ten years were more erratic with some successes like Stolen Kisses [1968] and The Wild Child [1970] and several disappointments, which were either box office flops (Fahrenheit 451 [1966]) or poorly received by French critics such as The Bride Wore Black [1968]. Then he revived his career and critical standing with two masterpieces in a row, Day for Night (1973) and The Story of Adele H. (1975). The former was a delightful, audience-pleasing homage to moviemaking which was nominated for four Oscars (and won for Best Foreign Language Film) but the latter was a much darker affair, based on real events, and focused on an obscure literary figure, Adele Hugo, the fifth and youngest child of Victor Hugo, who was one of France’s most famous writers and poets.

Continue readingTag Archives: Pauline Kael

Bottom Feeders

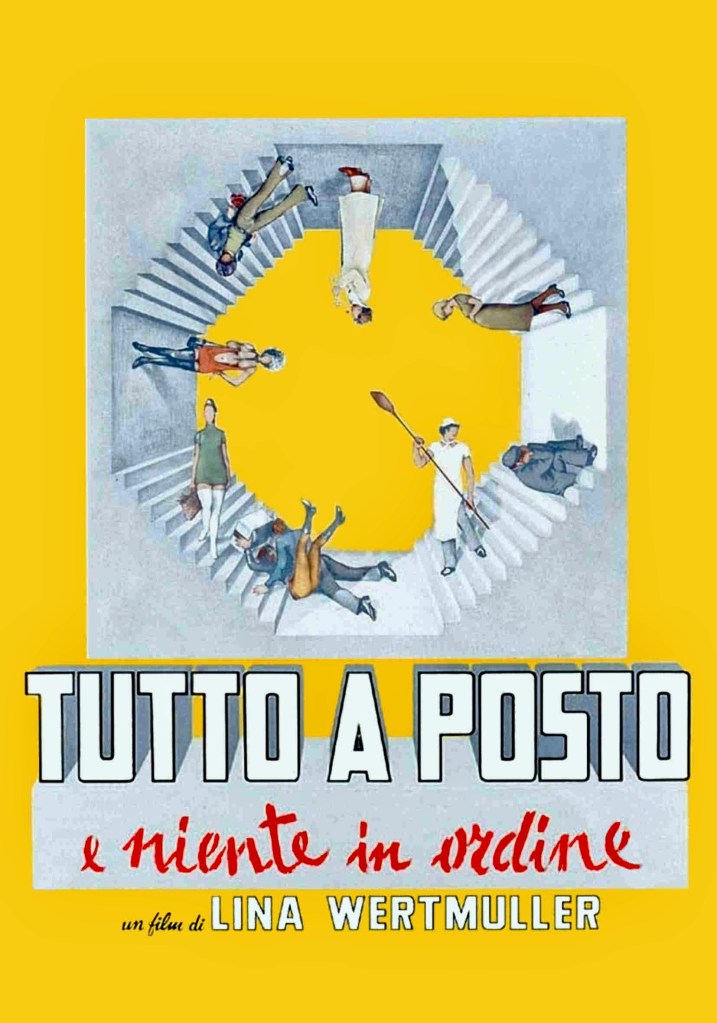

Gigi and Carletto are two naïve country bumpkins who, like many others from rural Italy and southern regions like Sicily, have come to the northern city of Milan to seek their fortunes. They soon fall in with other recent arrivals to the city seeking work and eventually set up a communal living situation in an abandoned apartment with others. Both men have big dreams and expectations but the reality is quite different from what they imagined and they fall prey to the city’s corrupting influences. It is a familiar scenario that you have probably seen in numerous other movies but director Lina Wertmuller gives it her own unique spin in Tutto a posto e niente in ordine (English title: All Screwed Up, 1974), an exuberant, gleefully crude satire that uses broad comedy and eccentric characters to magnify the myriad problems of Italy during the early 70s. This is her idiosyncratic contribution to Commedia all’italiana, a genre of comedic social commentary first created by Mario Monicelli and Pietro Germi in the late fifties/early sixties with such films as Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958) and Divorce Italian Style (1961), satires where serious themes like poverty, unemployment, marital woes and economic hardships are treated in a lighthearted style.

Continue readingFree Spirits

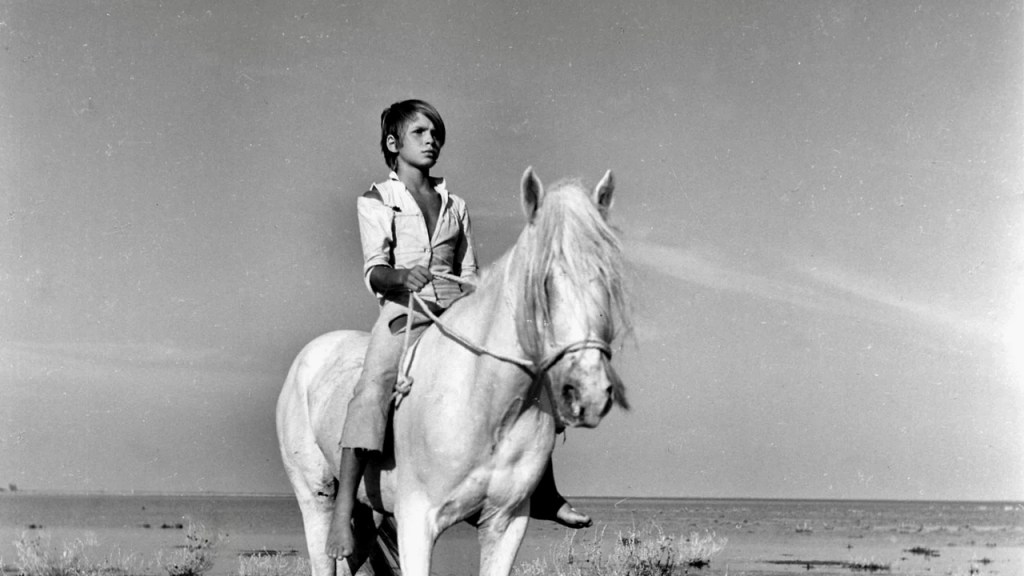

When you consider movies made for children and/or family viewing, stories about horses constitute a large portion of the genre, especially in American cinema. My Friend Flicka (1943), Black Beauty (1947), The Story of Seabiscuit (1949), Snowfire (1957), The Sad Horse (1959) and The Black Stallion (1970) are just a few of the more famous titles and some of these have inspired remakes or sequels. Still, one of my favorite films in this category comes from France and is often overlooked today – Crin Blanc: Le Cheval Sauvage (English title: White Mane, 1953), written and directed by Albert Lamorisse (1922-1970).

Continue readingHere Today, Gone Tomorrow

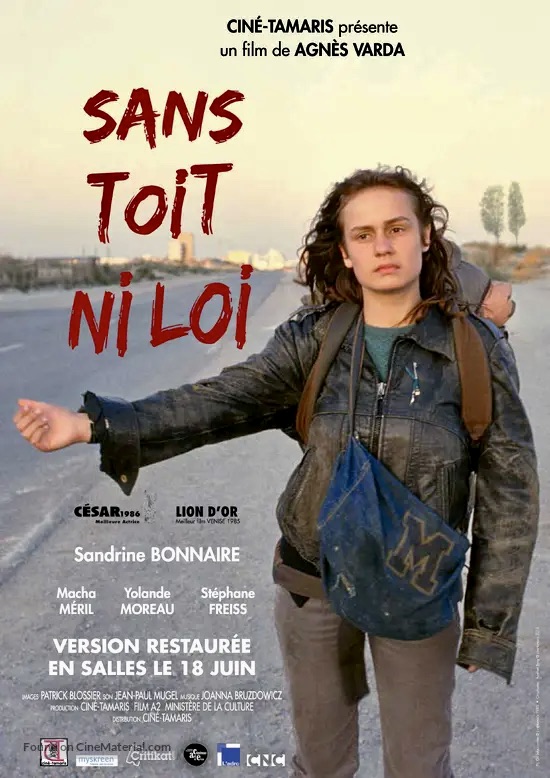

Film critics and moviegoers familiar with the work of French filmmaker Agnes Varda were unprepared for her seventh feature film Sans toit nil oi (English title: Vagabond) when it hit theaters in 1985. It had been eight years since her previous dramatic work One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977), an optimistic, semi-musical tale of female solidarity and friendship during the rise of the feminist movement in France, and her new feature couldn’t have been more different or unexpected. Nor did any of her earlier features – the New Wave influencer La Pointe Courte (955), Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), Le Bonheur (1965), Les Creatures (1966) or the experimental happening Lion’s Love (1969) – prepare viewers for the harsh realities and raw authenticity of Vagabond. Certainly the film was partially shaped by Varda’s own experience in documentary filmmaking but it also exerted a dramatic power and an almost visceral visual sense that was not apparent in the director’s previous dramatic work. Based on Varda’s encounter with a female vagrant, Vagabond focuses on the final weeks in the life of a homeless woman named Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire) who meets and interacts with various people along the roads of southern France before dying of exposure in a vineyard during a harsh winter.

Continue readingThe Spider and the Fly

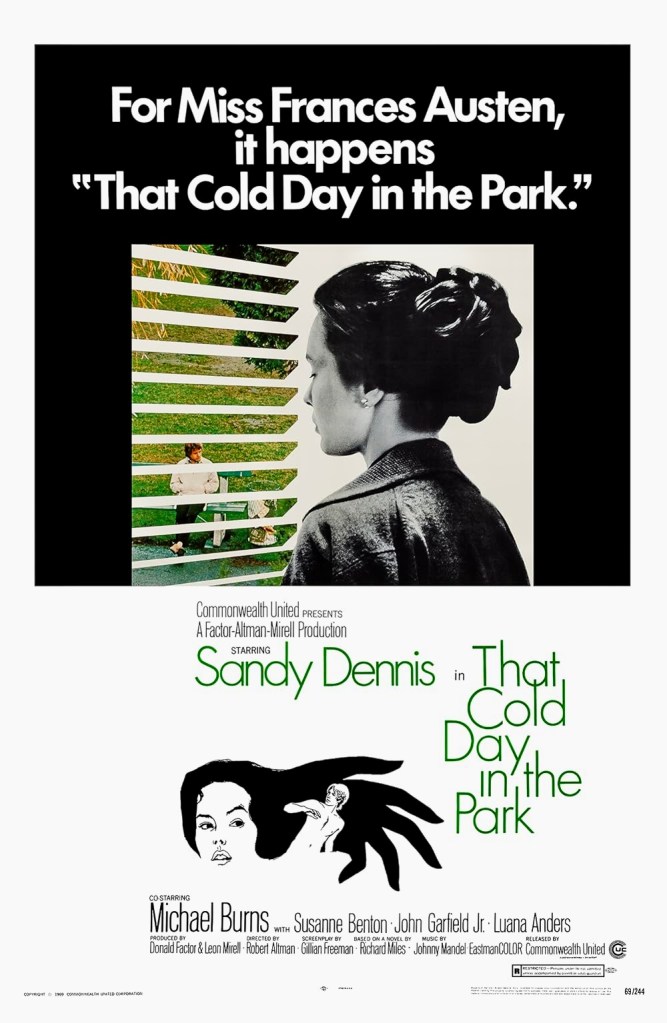

Most film critics and movie lovers point to Nashville (1975) as Robert Altman’s masterpiece, although I’ve always been partial to his unique spin on the Western, McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971). I also admire an earlier film that he directed that was conspicuously absent or missing from his filmography in most of the obituaries on the director after he died. That Cold Day in the Park was made between Countdown (1967) and M*A*S*H* (1970) in 1969 and was based on a novel by Richard Miles. The screenplay was by British screenwriter Gillian Freeman, who had written the novel and film adaptation of The Leather Boys (1964), Sidney J. Furie’s drama about a troubled working class marriage and the husband’s friendship with a closeted gay biker.

A gender twist on John Fowles’s The Collector, That Cold Day in the Park stars Sandy Dennis as Frances Austen, a lonely spinster whose apartment overlooks a park in Vancouver. One wet, wintry day she spots a young man on a park bench who appears to be homeless. She invites him into her home to get warm but ends up encouraging him to stay. The fact that the stranger (Michael Burns) pretends to be mute only adds to the ensuing strangeness. His little joke backfires, however, when he arouses Dennis’s long-suppressed sexual feelings and becomes a prisoner in her apartment.

Continue readingMan of Mystery

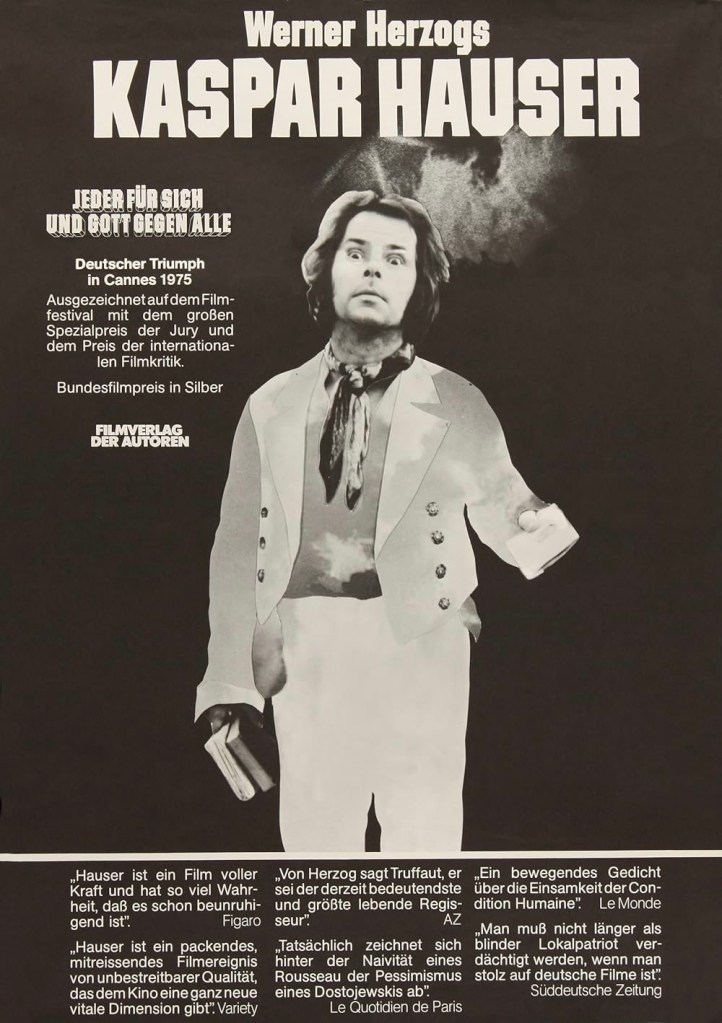

In May 1828 a young man appeared in a town square in Nuremberg, Germany carrying a prayer book and two letters written by his former caretaker. He spoke very little and was unable to answer any questions about his identity, where he came from or why he was there. One of the letters stated that he had come to the city to meet the captain of the 6th cavalry regiment with the hope of becoming a cavalryman. The other letter claimed he had been born in 1812 and had been raised in complete isolation from other people although he had been taught rudimentary reading and writing skills. His name was Kaspar Hauser but his mysterious nature and childlike presence baffled the townspeople and he was housed as a vagabond at the local prison until he was made a ward of the city and put under the protective care of Lord Stanhope, a wealthy aristocrat. Stanhope devoted himself to Hauser’s further education and re-entry into society and the young man’s bizarre demeanor aroused the curiosity of the public as well as doctors, professors and members of the clergy. Unfortunately, Hauser’s life came to an abrupt end in April 1833 when the mysterious man who first brought him to Nuremberg returned and stabbed him to death, escaping without a trace. The case has been a source of fascination for years in Germany and numerous films, television series and made-for-TV movies have been made about him but The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser aka The Mystery of Kaspar Hauser aka Every Man for Himself and God Against All (German title: Jeder fur Sich und Gott Gegen Alle, 1974), directed by Werner Herzog, is probably the most famous and critically acclaimed of all the versions made to date.

Continue readingGoing Bananas!

In the early 1970s midnight movies became a craze after the Elgin Theatre in New York discovered a surprise hit with Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970). Soon other theatres across the country launched their own midnight film series and movies like Night of the Living Dead (1968), Pink Flamingos (1972), The Harder They Come (1972) and Harold and Maude (1972) began to attract audiences that missed those movies during their limited initial release. Some of those early midnight movie choices were surprising and included Hollywood classics like Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940), the rock ‘n’ roll satire The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) and the WW2 era musical The Gang’s All Here (1943). Yet, when you consider the fact that a lot of those early midnight movie screenings were attended by younger audiences, many high on pot or other substances, it starts to make sense. The Gang’s All Here, in particular, with its eye-popping dayglo Technicolor hues, surreal art direction and outlandish dance choreography is as psychedelic and mind-blowing as the “trip sequence” in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Continue readingThe Price of Fame

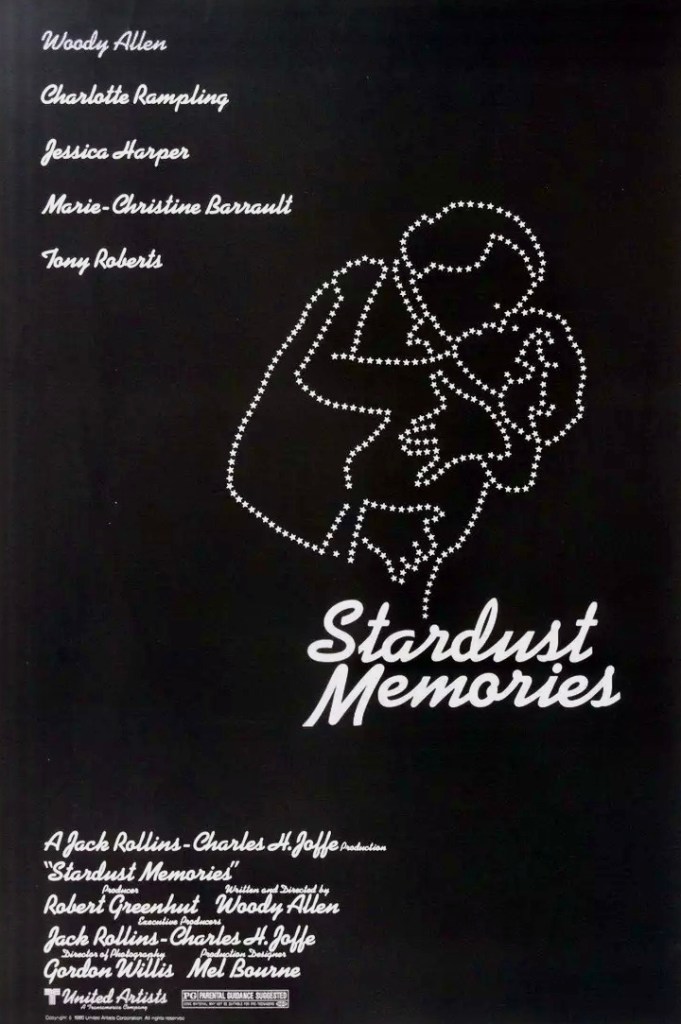

After directing more than fifty feature films including the three-part New York Stories (1989) with contributions from Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese and the re-edited/re-dubbed version of a Japanese spy thriller retitled, What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (1966), Woody Allen has one of the most impressive filmographies of any living director in Hollywood. Regardless of what you think about him as a person due to the controversy that surrounded his marriage to adopted stepdaughter Soon-Yi Previn, one can’t deny all of the critical acclaim he has amassed over the years, which includes 24 Oscar nominations, three of which won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay (Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters and Midnight in Paris). Not all of his films have been box office hits and some have been minor efforts or polarizing like September (1987) or Deconstructing Harry (1997), but the true acid test for any fan or critic who loves Woody Allen movies is Stardust Memories (1980), his most misunderstood and generally maligned tenth feature about the downside of being famous.

Continue readingRupert Pupkin’s Stand-Up Act

Some movies are prescient or ahead of their time but audiences and film critics often don’t notice until many years after the original release. Sidney Lumet’s Network (1976), written by Paddy Chayefsky, is one example, but so is The King of Comedy (1983), which unlike Network, was a major box office bomb for director Martin Scorsese and received mixed reviews from the critics. Yet, it seems more relevant than ever about the cult of celebrity and the public’s obsession with the rich and famous. Although The King of Comedy was promoted as a comedy, some critics and moviegoers found the film too dark and disturbing and felt Rupert Pupkin, the title character, was just as delusional and dangerous in his own way as Travis Bickle, the anti-hero of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976).

Continue readingSatyajit Ray’s Days and Nights in the Forest

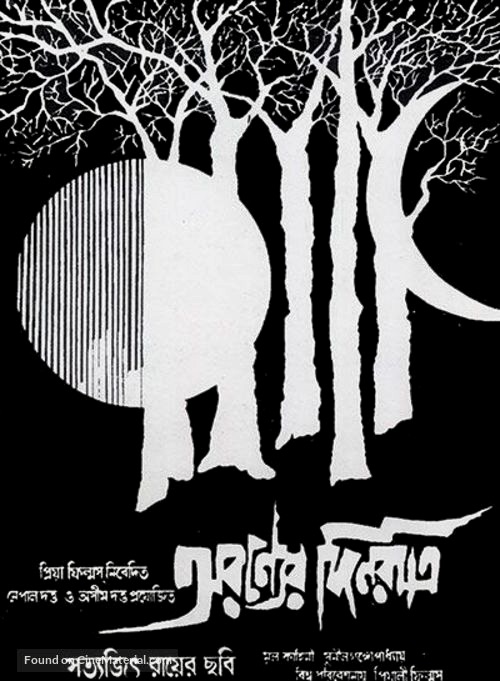

Four carefree middle class bachelors from Calcutta journey deep into the bucolic countryside for a break from city life and to enjoy drinking and partying with the local native women. What they end up experiencing in this unfamiliar locale is both a reflection of their own ignorance and colonialist attitudes inherited from their former British occupiers about the lives of people in rural India. This is the basic premise of Ananyer Din Ratri (English title: Days and Nights in the Forest, 1970), which many film scholars and critics consider a mid-career masterpiece from director Satyajit Ray. Admirers of the movie also cite the plays of Anton Chekhov and the films of Jean Renoir, especially his 1946 short Partie de Campagne (English title, A Day in the Country) as distinct influences on this social comedy with its amusing and sometimes harsh observations about human foibles and cultural differences.

Continue reading