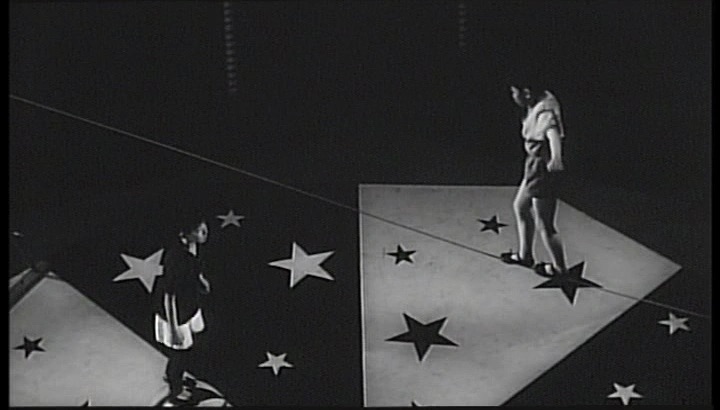

When was the last time you went to the circus? For most people, that form of popular entertainment has changed drastically over the years and is now more likely to be a showcase for human acts like Cirque de Soleil than one featuring performing animals (dancing elephants, lion taming, horses leaping through hoops of fire, etc). But there was a time from the late 19th to the middle of the 20th century when circuses were the ultimate family entertainment. Movies, in particular, captured the golden age of the circus in a variety of genres that ranged from big screen spectacles (The Greatest Show on Earth [1952], Circus World [1964]) to slapstick comedies (The Circus [1928], At the Circus [1939]) to Walt Disney fare (Dumbo [1941], Toby Tyler or Ten Weeks with a Circus [1960]) to horrific murder mysteries (Circus of Horrors [1960, Berserk [1967]). Yet, there are few, if any, that merge fantasy and reality in the style of Japanese director Kaizo Hayashi’s Nijisseiki Shonen Dokuhon (English title: Circus Boys, 1989). This balancing act is also matched metaphorically through the two main protagonists who must learn to come to terms with gravity, whether it is riding an elephant, walking a tightrope or finding stability in their lives.

Continue reading