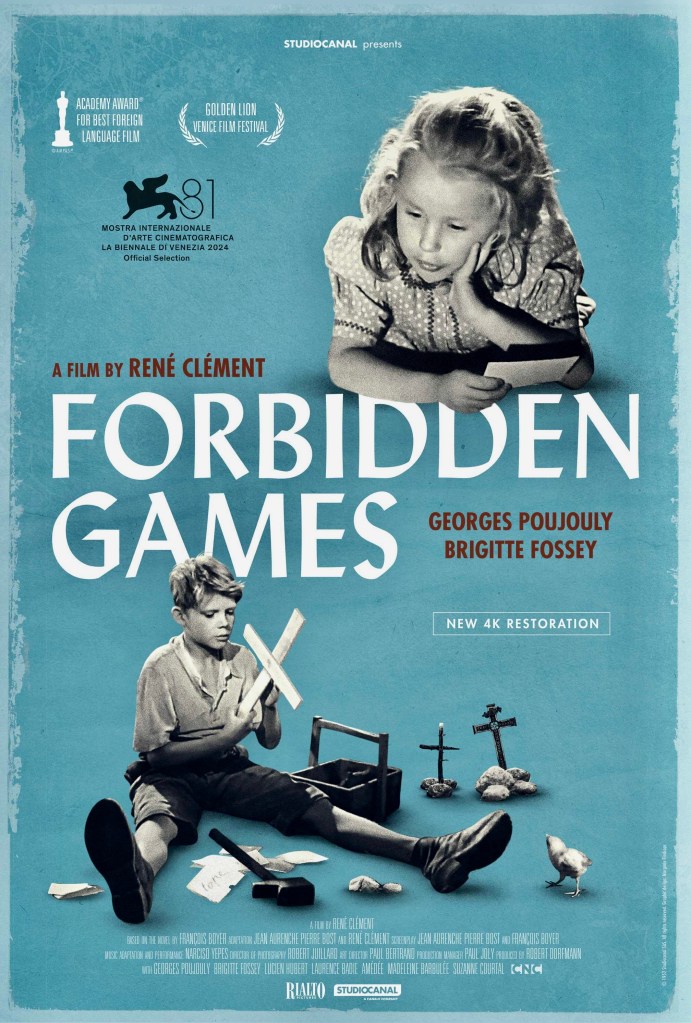

June 1940. A long line of French refugees flee Paris for the countryside during the German invasion of France in WW2. Among the evacuees are a young couple with their 5-year-old daughter Pauline and her pet dog Jock. When the couple’s car stalls on the road, angry refugees push it out of the way and down a hill. The family grab whatever they can carry from their stranded vehicle and return to the road as German aircraft start dropping bombs. In the confusion, Jock runs off and Pauline chases after him. Her parents follow in pursuit but the family is forced to take shelter again as aerial machine-gunners target the escaping Parisians. This time the parents and the dog are mortally wounded and Pauline is left abandoned. She wanders into the countryside clutching her dead pet, not really comprehending what has happened to her. All of this occurs in the few ten minutes of Jeux Interdits (English title: Forbidden Games), one of the most powerful war films of all time. Yet, it is unique within its specific genre because it does not focus on the war itself but the effects of the devastation on a young child. Directed by Rene Clement, the film became an international sensation and won a honorary Oscar as Best Foreign Film of 1952.