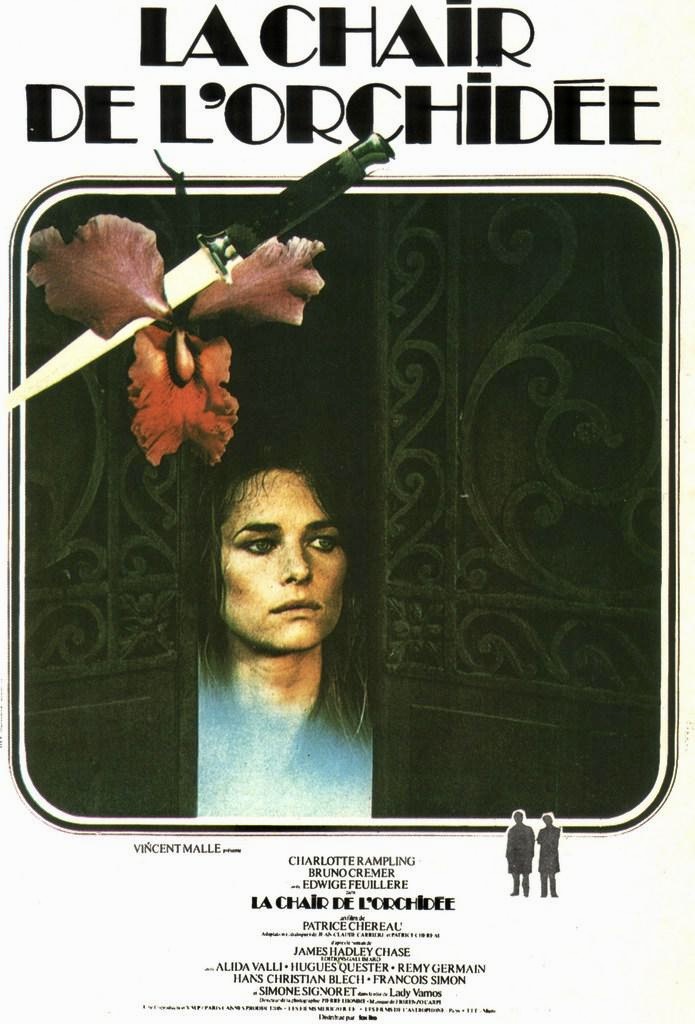

Charlotte Rampling has been an international star since the mid-1970s when she appeared in Zardoz (1974), The Night Porter (1974) and Farewell, My Lovely (1975), but during her early career, critics were more likely to comment on her beauty and sex appeal over her acting talent. It wasn’t until she began appearing in the films of Francois Ozon (Under the Sand [2000], Swimming Pool [2003]) and other independent, cutting-edge directors like Dominik Moll (Lemming, 2005) and Laurent Cantet (Heading South, 2005) that Rampling finally came into her own as a critically acclaimed actress and cult favorite. She has rarely steered clear of edgy material or doing nude scenes or choosing unconventional roles over more audience friendly fare and her movies from the late sixties through the mid-nineties reflect this. Some were pretentious misfires like The Ski Bum (1971) or eccentric one-offs (Yuppi du, 1975) or mainstream showcases for her talent such as Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories (1980) and Sidney Lumet’s The Verdict (1982). Yet, even her lesser known work from this period is often worth seeking out and La Chair de I’orchidee (English title, The Flesh of the Orchid, 1975), the debut film of French director Patrice Chereau, is certainly a wild card. A psychological thriller that seems to take place in an alternate universe where everyone is misanthropic, corrupt, greedy or violent, Chereau’s first film is based on a 1948 pulp fiction novel by James Hadley Chase.

Continue readingTag Archives: Charlotte Rampling

The Price of Fame

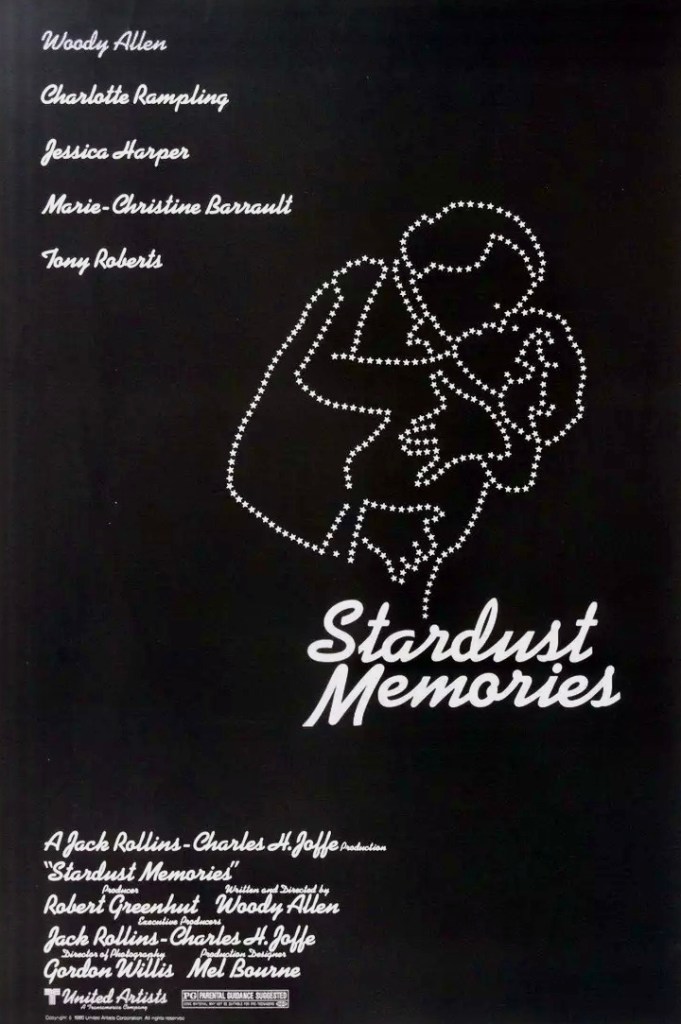

After directing more than fifty feature films including the three-part New York Stories (1989) with contributions from Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese and the re-edited/re-dubbed version of a Japanese spy thriller retitled, What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (1966), Woody Allen has one of the most impressive filmographies of any living director in Hollywood. Regardless of what you think about him as a person due to the controversy that surrounded his marriage to adopted stepdaughter Soon-Yi Previn, one can’t deny all of the critical acclaim he has amassed over the years, which includes 24 Oscar nominations, three of which won the Academy Award for Best Screenplay (Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters and Midnight in Paris). Not all of his films have been box office hits and some have been minor efforts or polarizing like September (1987) or Deconstructing Harry (1997), but the true acid test for any fan or critic who loves Woody Allen movies is Stardust Memories (1980), his most misunderstood and generally maligned tenth feature about the downside of being famous.

Continue readingSwinging Down the Street So Fancy Free

A frumpy woman in her early twenties dreams of being loved but despite her continual attempts to have a romance finds herself observing life from the sidelines, barely noticed by those around her. Reduced to a one sentence description, Georgy Girl (1966) sounds dreary and depressing but on-screen this tale of a desperately lonely woman unfolds as a madcap, often irreverent farce which at times is cruelly indifferent to the sad-sack characters it parades before us. This is a film where tone is everything and Georgy Girl, directed by Silvio Narizzano, is distinctively different in this respect, standing out from countless other cinematic tearjerkers about ugly ducklings and lonely spinsters. The film also captures London at the height of the Swingin’ Sixties when everything seemed like a put-on or a come-on.

Continue readingDisconnected and Lost in Capri

When did alienation in modern society become a favorite thematic concern in the culture and the arts, particularly in the cinema? Certainly the films of Michelangelo Antonioni addressed the inability of people to connect, feel or relate to each other in a post-industrial age world as early as 1957 in Il Grido. But by the early sixties, it seemed as if every major film director in the world was addressing the topic on some level. A general sense of malaise was in the air as if the modern world was having a counterproductive effect on humanity, creating a sense of futility, amorality or complete apathy. You could see aspects of this reflected in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad (1961), Luis Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1961) and Jean-Luc Godard’s My Life to Live (1962). All of these are considered cinematic masterworks of the 20th century but there are also many worthy and lesser-known contributions to the pantheon of alienation cinema and one of the most strikingly is Il Mare (The Sea), the 1963 directorial debut of Giuseppe Patroni Griffi. Continue reading

When did alienation in modern society become a favorite thematic concern in the culture and the arts, particularly in the cinema? Certainly the films of Michelangelo Antonioni addressed the inability of people to connect, feel or relate to each other in a post-industrial age world as early as 1957 in Il Grido. But by the early sixties, it seemed as if every major film director in the world was addressing the topic on some level. A general sense of malaise was in the air as if the modern world was having a counterproductive effect on humanity, creating a sense of futility, amorality or complete apathy. You could see aspects of this reflected in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad (1961), Luis Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1961) and Jean-Luc Godard’s My Life to Live (1962). All of these are considered cinematic masterworks of the 20th century but there are also many worthy and lesser-known contributions to the pantheon of alienation cinema and one of the most strikingly is Il Mare (The Sea), the 1963 directorial debut of Giuseppe Patroni Griffi. Continue reading