Most fans of classic Hollywood horror films probably remember the first time they saw a Universal horror picture. My first exposure was at age 5 when my parents allowed me to stay up late and watch The Wolf Man (1941) with them. After that, a lot of those early years in Memphis, Tennessee were spent watching “The Late Show” with babysitters while my parents were either attending or giving a cocktail party. Every Saturday night some horror favorite from Universal would air and The Mad Ghoul (1943) was a particularly fond memory. But the one that really stayed with me was House of Horrors (1946) featuring Rondo Hatton as “The Creeper.”

Continue readingGood Cop, Bad Cop

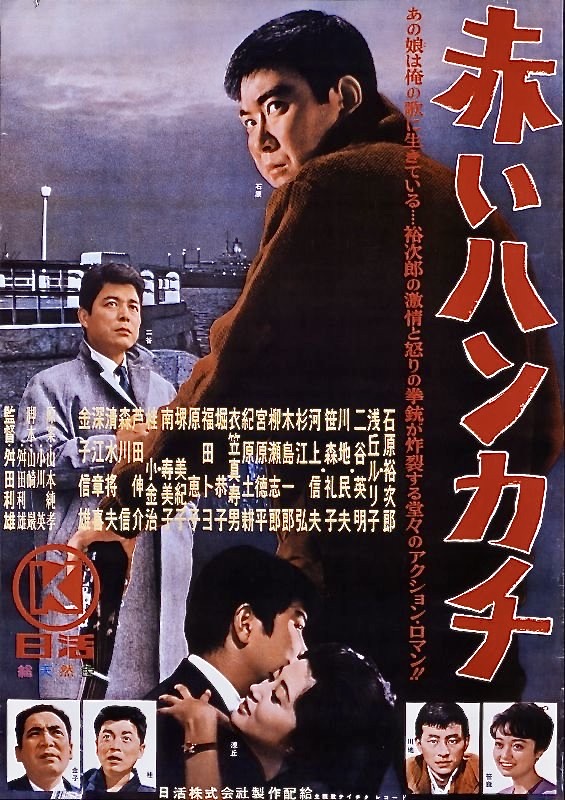

Among the major film studios in Japan, Nikkatsu is generally regarded as the oldest but it almost didn’t survive the post-WW2 years after shutting down production in 1942. When it relaunched in 1954, audience tastes had changed and so had the moviegoing public, which was younger and hungry for films that reflected the problems, attitudes and pop culture of their generation. As a result, the studio began to churn out different kinds of films – yakuza and cop thrillers, youth rebellion dramas and frenetic comedies/musicals – that were partially inspired by American genre films and the rise of rebel icons like James Dean and Elvis Presley. Often categorized as “Nikkatsu Action Cinema,” these films experienced a surge of popularity in the late 50s as such directors as Seijun Suzuki, Shohei Imamura, Koreyoshi Kurahara and Toshio Masuda emerged as the most creative filmmakers at Nikkatsu during the post-war new wave. Masuda, in particular, was one of the most commercially successful filmmakers at the studio and helped actor Yujiro Ishihara achieve major stardom after their first collaboration Rusty Knife (1958), a gritty crime drama about a volatile street tough who crosses the mob. They went on to make 25 features together but, curiously enough, one of their most successful films, Akai Hankachi (Red Handkerchief, 1964), is almost forgotten and difficult to see outside of Japan.

Continue readingThe Ship of Heaven

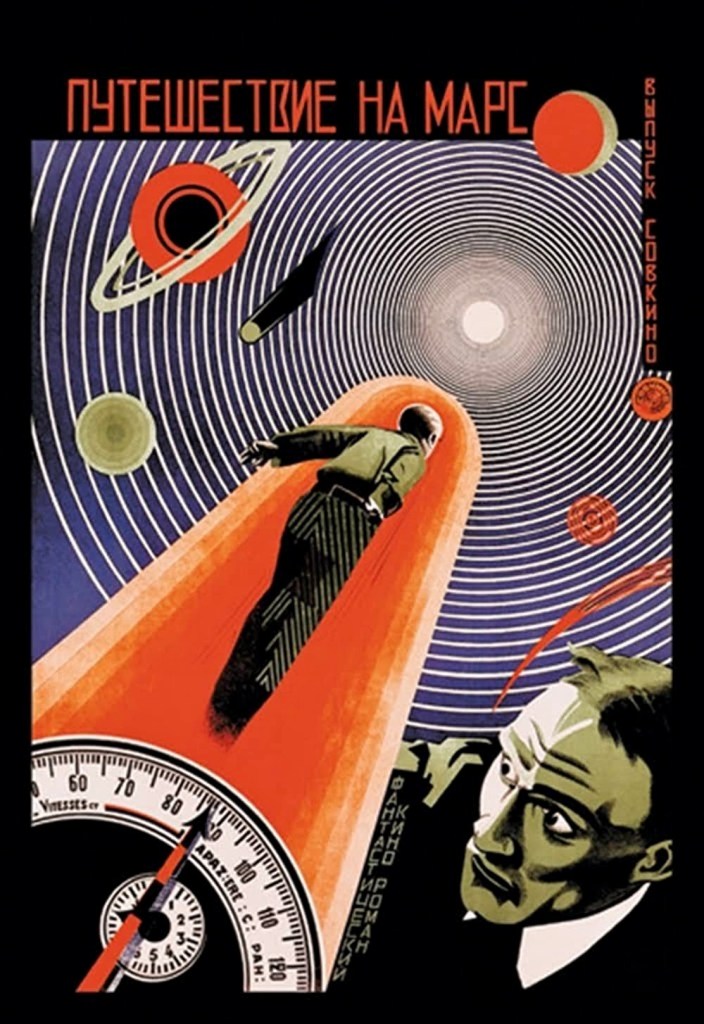

Space travel was truly a visionary concept when Jules Verne first introduced it in his 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon and it continued to attract readers when H.G. Wells explored the idea further a few years later in 1901’s First Men in the Moon. Although both authors were fascinated with science and technology, these novels were essentially outlandish adventures with elements of humor and satire. Even the first acknowledged film about an expedition into outer space—Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon (1902)—was a whimsical fantasy rather than a realistic approach to the subject. Fifteen years later, the release of the Danish film A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet), directed by Holger-Madsen, announced a new kind of approach.

Down and Out in Chicago

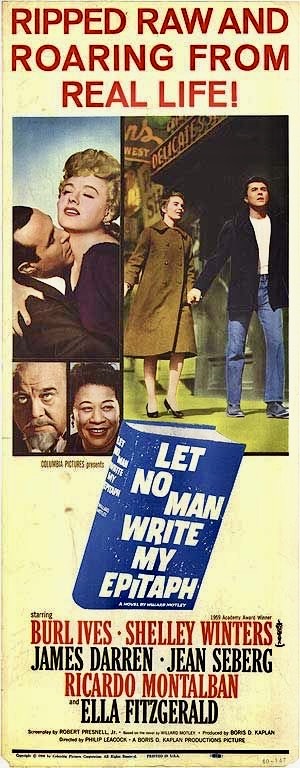

At the end of the 1949 Nicholas Ray film, Knock on Any Door, juvenile delinquent Nick Romano, played by John Derek, is sentenced to die in the electric chair for killing a cop, despite the attempts of his attorney, Andrew Morton (Humphrey Bogart), to save him. The story didn’t end there, however, and African-American novelist Willard Motley wrote a sequel to his original 1947 bestseller in 1958 entitled Let No Man Write My Epitaph. It was adapted to the screen under that same title in 1960 and focused more on the ghetto drug problem than urban gang violence although the latter is still an omnipresent concern.

Continue readingClaude Goretta’s Garden Party

Most people who work for a company, regardless of its size, have probably attended an office party for the employees at a certain point. For some, the idea of socializing with co-workers outside of work is something to avoid if possible. For others, it is an opportunity to score points with the boss and maybe advance your career. Then there are employees who simply enjoy social gatherings where an open bar and free food is theirs for the taking. All of these personality types and more – the gossip, the prude, the party animal, etc. – are on display in The Invitation (French title: L’invitation, 1973), a comedy of manners by Swiss director Claude Goretta, in which the employees of a small firm gather at a country estate for an office party given by one of the most unlikely employees to host a soiree.

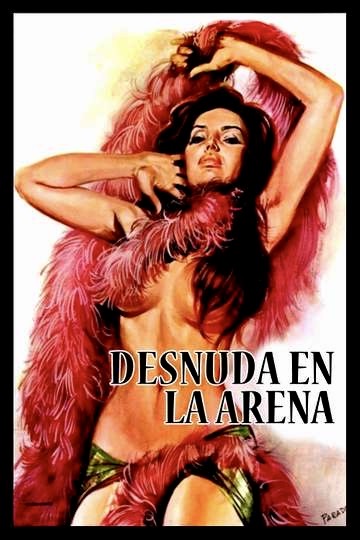

Continue readingIsabel Sarli Bares All

Nude in the Sand sounds like one of those sex-themed cocktails with names like Between the Sheets, Strip and Run Naked and Sex on the Beach that are offered at trendy under 30 bars but no. It is the English language title of Furia Sexual: Desnuda en la Arena (1969), which is also known as Alone on the Beach, and stars Argentinian sexpot Isabel Sarli. If you know the name, it is probably because cult director John Waters is a big admirer of Sarli’s films and has regularly screened Fuego (1969), probably her most infamous and delightfully campy opus, to stunned audiences over the years. Nude in the Sand may not top the delirious highs and lows of Fuego but it is an enjoyably trashy introduction to the voluptuous Sarli for novices as well as a must-see for fans of Fuego.

Continue readingAttack of the Molecular Men

The atom bomb and its devastating after effects have served as the basis for some of the science fiction genre’s most popular and successful films and it’s no surprise that many of them hail from Japan where Gojira (1954, U.S. title: Godzilla) became the first in a long line of radioactive monsters bent on stomping Tokyo. Whether intended as metaphorical retribution for the A-bomb destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 or cautionary tales about the dangers of nuclear power, these sci-fi fantasies became Toho’s studios’ most profitable exports during the late fifties and early sixties and eventually spawned subgenres of their own, one of which was the “mutant” series. The masterminds behind Gojira and most of the Toho sci-fi releases were director Ishiro Honda and special effects technician Eiji Tsuburaya and their first effort in the “mutant” series – Bijo to Ekitainingen (1958) – still stands as one of their most unusual and distinctive films.

Continue readingStrangers on a Gondola

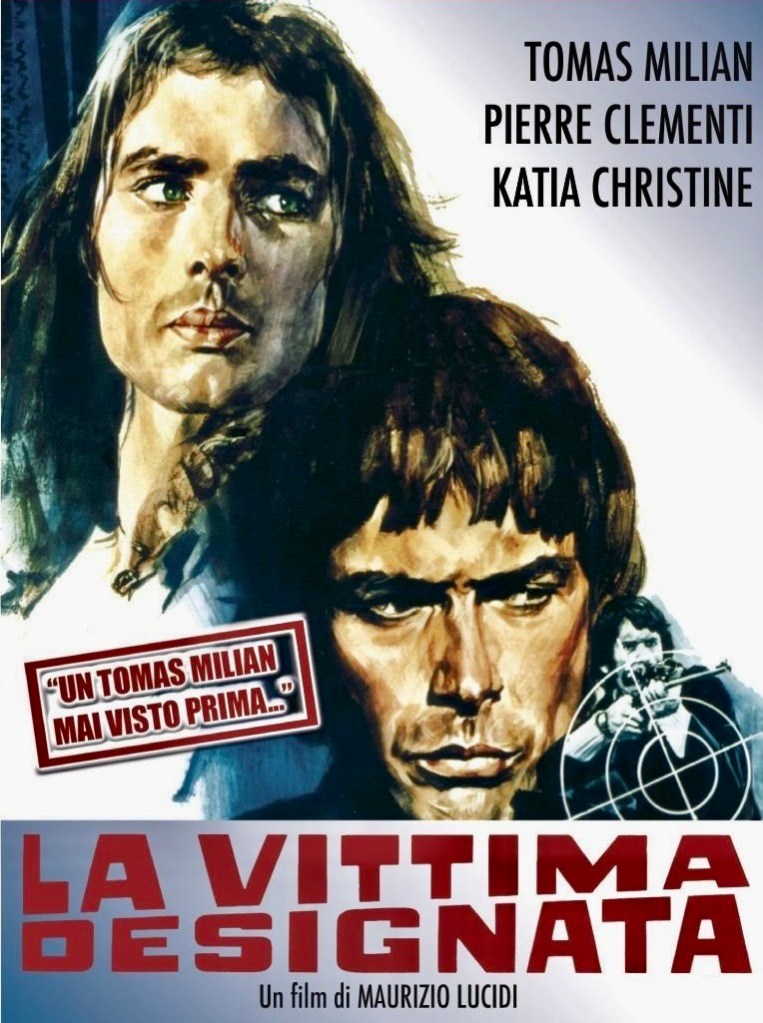

The first Patricia Highsmith novel to be adapted to film was the author’s first book, published in 1950, Strangers on a Train, which Alfred Hitchcock made into a movie the next year. Yet, with the exception of U.S. television which adapted some of Highsmith’s stories for the small screen (The Talented Mr. Ripley for Studio One in Hollywood in 1956, The Perfect Alibi for Jane Wyman Presents The Fireside Theatre in 1957, Annabel for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in 1962), no American film director would attempt another Highsmith screen adaptation for many years. European filmmakers, however, have returned again and again to her perversely fascinating thrillers which are marked by their disturbing psychological detail and macabre humor. Among these are René Clément’s visually stunning Purple Noon (1960), an adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley, Claude Autant-Lara’s Enough Rope (1963), based on the novel The Blunderer, Wim Wenders’ hallucinatory noir The American Friend (1977), adapted from Ripley’s Game, This Sweet Sickness (1977) by French director Claude Miller, and most famously Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999). Yet, one of the least known – and uncredited – adaptations is La Vittima Designata (English title: The Designated Victim, 1971), which is a very loose, revisionist version of Strangers on a Train with colorful Italian location shooting in Venice, Milan and Lake Como.

Continue readingDream Time or Real Time?

Have you ever woken up from a dream that was almost ordinary in the way it unfolded yet it left you with a feeling that it had taken place in some ethereal twilight zone? That is the best way that I can describe the experience of watching Appointment in Bray aka Rendez-vous a Bray (1971), Andre Delvaux’s artful adaptation of the Julien Gracq short story, Le Roi Cophetua. On the surface, the film has the structure of a traditional character study but is actually much closer in tone and atmosphere to a cinematic haiku, one that offers meditative reflections on memory, friendship and the debilitating effects of war.

Continue readingPistol Packin’ Femme Fatales

Juvenile delinquent films in the 1950s were so plentiful that they became a major B-movie subgenre and the surprisingly thing about that was the number of movies featuring female hooligans. Among some of the more famous titles are Reform School Girl (1957), Runaway Daughters (1956) and Teenage Devil Dolls aka One Way Ticket to Hell (1955) but Girls on the Loose stands out from the pack as a little known and ingenious B-movie delight. For one thing, these aren’t gum-chewing high school delinquents but a quartet of hardened professionals and damaged goods. Equally surprising is the tough, no nonsense story arc which makes the most of its low budget sets and noir lighting schemes in a compact 77-minute programmer directed by Paul Henreid. Yes, THAT Paul Henreid, the former Warner Bros. heartthrob from Austria-Hungary who performed that romantic cigarette seduction of Bette Davis in Now, Voyager (1942). Here he is below, directing his incognito cast of Girls on the Loose.