Have you ever woken up from a dream that was almost ordinary in the way it unfolded yet it left you with a feeling that it had taken place in some ethereal twilight zone? That is the best way that I can describe the experience of watching Appointment in Bray aka Rendez-vous a Bray (1971), Andre Delvaux’s artful adaptation of the Julien Gracq short story, Le Roi Cophetua. On the surface, the film has the structure of a traditional character study but is actually much closer in tone and atmosphere to a cinematic haiku, one that offers meditative reflections on memory, friendship and the debilitating effects of war.

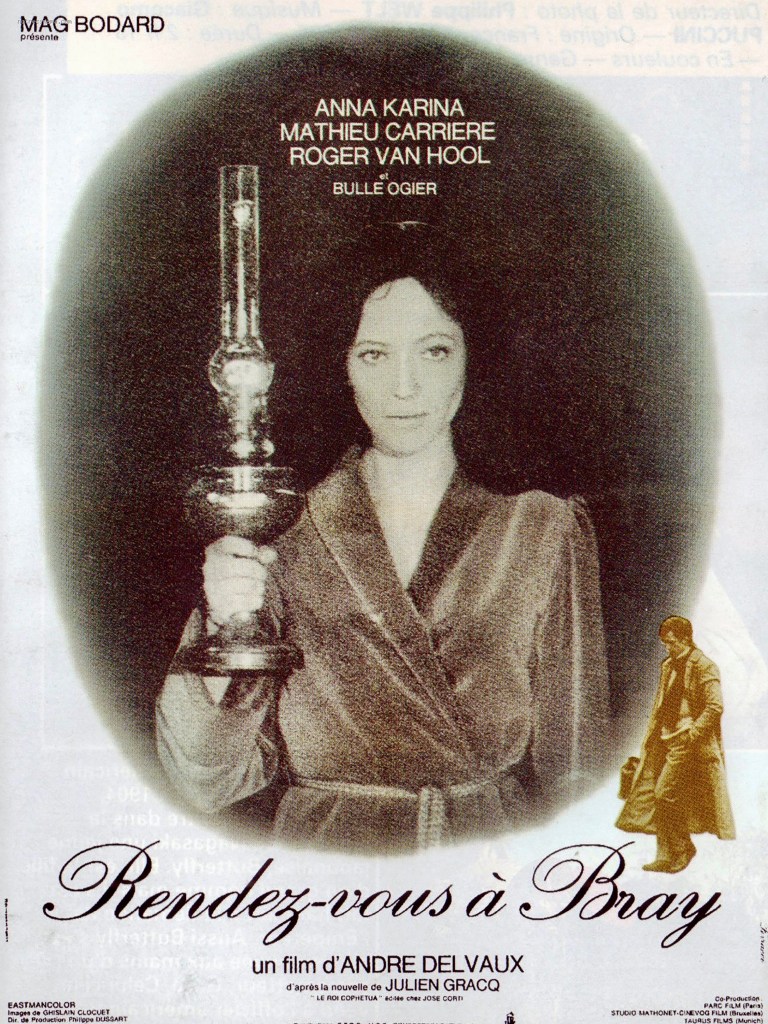

The movie opens in Paris in 1917 as Julien (Mathieu Carriere), a pianist and music critic from Luxembourg, receives a letter from his friend Jacques (Roger Van Hool), who invites him to his country estate in Bray. World War I is taking a toll on the country but Julien has managed to avoid combat because of his status (Luxembourg is a neutral country, which is why Julien was rejected by the French army). Jacques, on the other hand, is a flyer for a French squadron but plans to use his military leave to reconnect with his good friend. Although Julien looks forward to their meeting with great anticipation, the reunion never occurs for reasons that are never revealed.

Appointment in Bray is primarily focused on Julien, his journey to Bray and what he experiences there. But director Delvaux disrupts the linear narrative by shifting back and forth between Julien’s present situation and his past memories, all of which serve to reveal facets of our protagonist’s personality. Julien is what you might call an aesthete, someone who lives for his art and music. That is his bond with Jacques, who is also a lover of classical music and a fellow composer, but they couldn’t be more different in temperament and behavior. Jacques is a man’s man, fond of drink, women, and adventure, all of which comes from a background of aristocratic privilege. Julien comes from a different social/economic background (his parents operate a vineyard) which, combined with his non-military status, appears to make him feel like an outsider.

The first half of Appointment in Bray proceeds like a gothic mystery where Julien arrives at Jacques’s estate and is greeted by his housekeeper (Anna Karina), who is never identified by name. She serves Julien tea and meals but reveals little about herself and remains a mysterious, enigmatic presence through the film. Is she withholding information about Jacques and his whereabouts? As Julien becomes increasingly concerned about his friend’s fate, the atmosphere of expectation becomes palpable. In some ways it feels like a period piece masquerading as Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot or something even more abstract.

Julien’s initial exploration of Jacques’s estate and country home also has the feel of a slightly foreboding fairy tale in the matter of Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film version of Beauty and the Beast. You keep anticipating Jacques’s arrival but his housekeeper’s reticent behavior imbues the waiting time with a mixture of mystery and eroticism. In an unforeseen twist, Julien is seduced by the housekeeper but in the morning she has vanished without a trace. Was she a specter or just a figment of his imagination?

The narrative is also driven by Julien’s memories of his friendship with Jacques which are depicted in a series of revealing flashbacks involving Odele (Bulle Ogier), Jacques’s girlfriend, and Jacques’s overbearing mother (Luce Garcia-Ville). As a result, the film becomes a dream-like mediation on relationships and how they are tested by time and conflict.

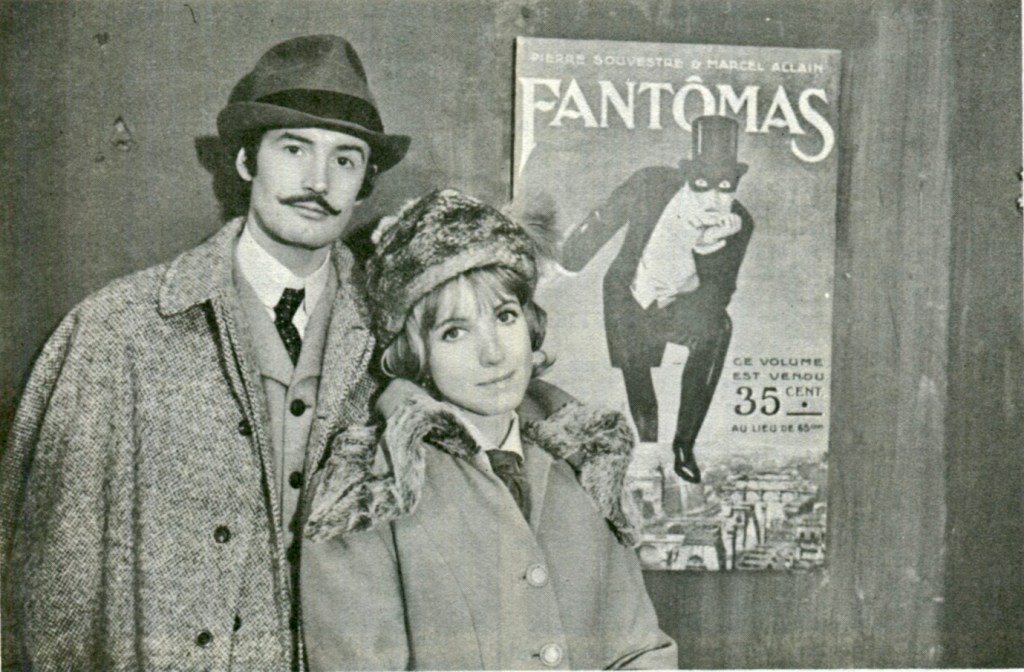

In one of the more telling incidents, Julien is playing the piano at a silent movie house which is showing Louis Feuillade’s serial thriller Fantomas (Director Delveux also worked as a pianist playing live scores for silent films at an early point in his career). Jacques and Odele enter the venue and sit behind him but after the screening, Jacques confronts him: “I think it’s despicable that you hide what you do from me.”

Julien: “I’m free to do what I like.”

Jacques: “Free to waste your life, free to wear out your fingers on a tinny theater piano. That must improve your touch.”

Julien: “It’s typically bourgeois to think that playing in a cinema is degrading.”

Jacques: “You said I’m a parasite that, unlike you, I have vices? Odile, look at him, this Jesus from Luxembourg. No alcohol, no women, no concessions to philistines…one day you’ll wake up and then it will hit you in the face and you will no longer dare to look in the mirror.”

Later, the trio of Julien, Jacques and Odile spend the evening at a bar and then walk come in the early morning hours through a forest. When they come upon a river, they decide to take a swim and disrobe in unison but Odile hesitates in joining them for a swim. We see her observing them as they splash around in the water, perhaps realizing that she will never be able to enter their private world. Unlike the fully engaged trio in Francois Truffaut’s Jules and Jim, these three people seem incapable of forming a menage a trois and Julien’s memories of the past seem to haunt him in ways that even he can’t comprehend.

Appointment in Bray was Delvaux’s third feature film and it is an exquisite visual and aural treat, thanks to the period production design by Claude Pignot (Stolen Kisses, Mississippi Mermaid), musical selections by Brahms, and the stunning cinematography by Ghislain Cloquet (The Fire Within, Au Hasard Balthazar). The pre-credit open has the look of a vintage daguerreotype and Cloquet uses a technique throughout the film that eloquently places it in its time period; he often opens a scene as if it is being viewed through a pinhole camera and then expands the oval image to reveal the surrounding details before returning to the pinhole view as the screen goes to black for the next scene.

Some of the non-dialogue sequences are the most memorable and employ a subtle mixture of sound design and still-life compositions such as a scene where Julien sits alone in the parlor of Jacques’s country home. We hear the rumblings of war in the distance as Julien observes the slight swaying of glass beads on a chandelier and ripples in a decanter of liquor. Even though actual combat or life in the trenches is never shown, Delvaux makes the war an omnipresent force that affects everyone and everything, even in a remote, insolated place like Jacques’s rural hideaway.

The main performances in Appointment in Bray are uniformly excellent but the real surprise is Mathieu Carriere, who creates a fascinating, sympathetic figure out of the cerebral protagonist of Gracq’s short story, which many claim was unfilmable. Prior to this, I was rarely impressed with Carriere as an actor and felt he was often typecast as effete, amoral characters with detached or aloof demeanors in such films like Coup de Grace (1976), A Woman in Flames (1983) and Love Rites (1987). He first attracted attention as a child actor in Rolf Thiele’s film adaptation of Tonio Kroger (1964), based on the Thomas Mann novella, and Volker Schlondorff’s Young Torless (1966), which won the FIPRESCI prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Carriere has gone on to dabble in both exploitation genre films and art film jewels while working with such renowned international directors as Andrzej Wadja (Gates to Paradise, 1968), Harry Kumel (Malpertuis, 1971), Andre Cayatte (Il n’y a pas de Fumee sans Feu, 1973), Marguerite Duras (Le Navire Night, 1979), Eric Rohmer (The Aviator’s Wife, 1981), and Karoly Makk (Hungarian Requiem, 1990). Carriere gives one of his finest performances in Appointment in Bray and he would go on to work with Delvaux in four more feature films.

Delvaux was an avid filmgoer for most of his life and eventually broke into the movie industry as a director of documentary shorts. He was almost forty when he directed his debut feature, The Man Who Had His Hair Cut Short (1965), but he was not a prolific director and his filmography only consists of eight feature films and one documentary, To Woody Allen from Europe with Love (1980). Still, Delvaux enjoyed a reputation among critics and moviegoers as a superb filmmaker in Belgium and Europe, winning awards and honors at numerous film festivals. For some reason, he remains almost unknown in the U.S. and very few, if any, of his work was distributed here. Admittedly, his films are unconventional in their emphasis on merging reality with dream states and some of his overt influences are magic realism novels and the surrealist movement. If you are an adventurous explorer of offbeat art cinema, however, Appointment in Bray is made for you.

Appointment in Bray is not currently available on any format in the U.S. but there are DVD options for you if you own an all-region DVD player that can read PAL discs. It is also available in a 7-disc Andre Delvaux Collection that was released in Belgium in 2013.

Other links of interest:

https://www.filmkultura.hu/regi/articles/profiles/delvaux.en.html

https://mynation.net/voice/german-activist/