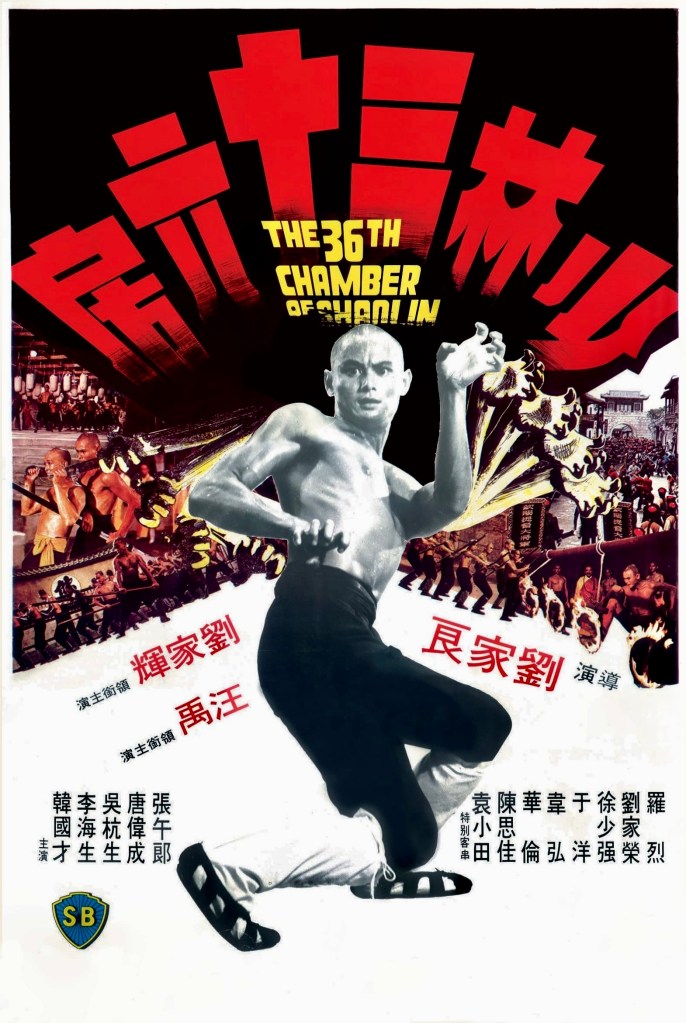

Did you know that there are more than 180 styles of martial arts practiced around the world and that includes karate, judo and other similar forms? Many experts trained in Chinese martial arts generally agree that one of the oldest forms of this practice and the most difficult to master is the Hung Gar style which can be traced back to the 17th century. That is also the time period featured in Shao Lin sans hi liu fang (English title: The 36th Chamber of Shaolin aka Master Killer aka Shaolin Master Killer, 1978). The film, directed by former actor Chia-Liang Liu (aka Lau Kar-Leung), is considered one of the cornerstones of Hong Kong martial arts cinema and it showcases the fluid movements and balletic grace of the Hung Gar style as practiced by its star, Chia-Hui Liu aka Gordon Liu.

Continue readingTag Archives: Hong Kong cinema

Dance of the Possessed

Remember the 1984 comedy All of Me, directed by Carl Reiner? In that film, Lily Tomlin plays a dying heiress who plans to have her soul transferred into the body of a younger woman but something goes wrong in the process and she ends up inhabiting the body of an attorney (Steve Martin). Imagine a horror fantasy variation of that premise and you have Li Gui Chan Shen (English title: Split of the Spirit, 1987), a Taiwanese film from director Fred Tan.

Continue readingWhere the Wild Things Are

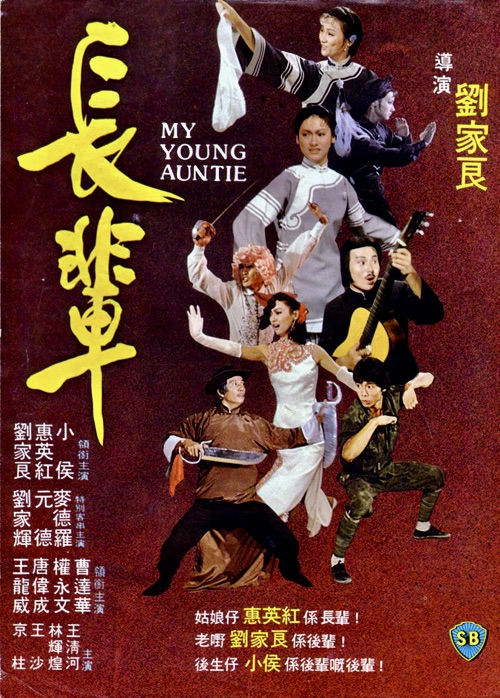

Remember the first wave of Hong Kong cinema to hit American movie screens in 1972? Bruce Lee was transformed into an international superstar after the release of The Big Boss and Fist of Fury and other martial arts masters like Jimmy Wang Yu and Lieh Lo developed cult followings for films such as One-Armed Boxer and Five Fingers of Death. Most of these movies were the product of a male-dominated film industry but, as early as the mid-sixties, female heroines begin to emerge in the genre as witnessed by Cheng Pei Pei in King Hu’s Come Drink with Me (1966). Others would follow like Angela Mao in Deadly China Doll (1973) and Kara Hui in My Young Auntie (1981).

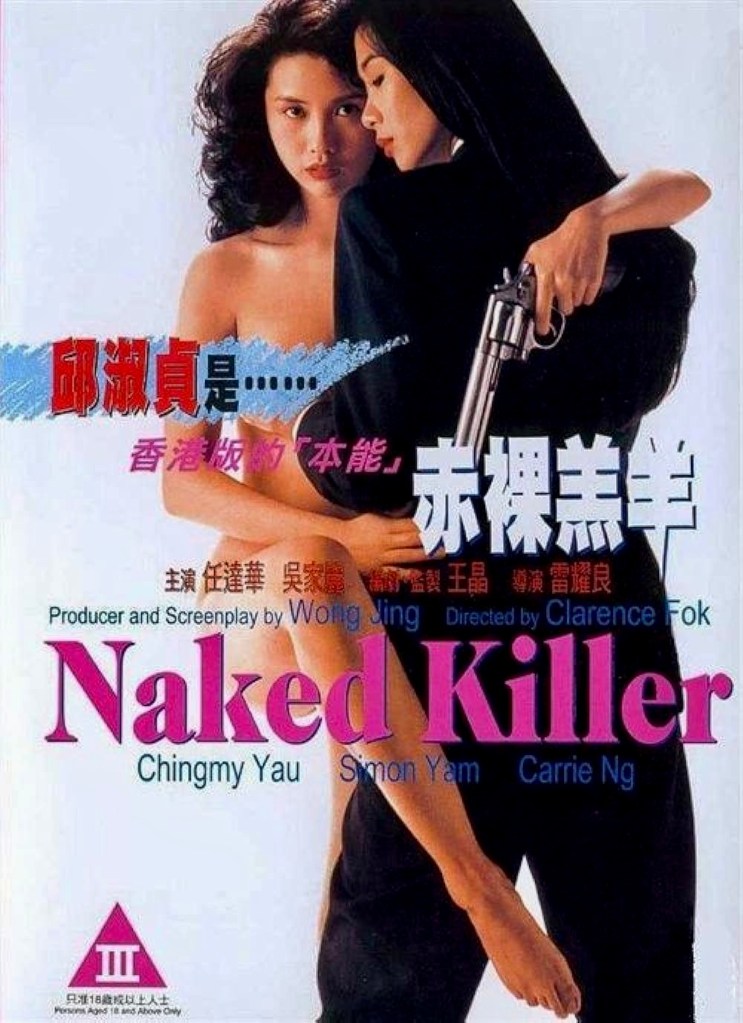

The Hong Kong movie business became even more diversified in 1988 after a new censorship ordinance created a rating system: Category I (general viewing), Category II (parental guidance) and Category III (adults only over 18 years of age). That third category quickly became notorious for an anything-goes-approach to the depiction of sex and violence on-screen. A major turning point was 1991 when Michael Mak’s Sex and Zen, Robotrix starring Amy Yip, and Black Cat with Jade Leung in the title role were among the first to push these boundaries to extremes in Hong Kong cinema. Martial arts actioners got even more outrageous the following year with the release of Chik Loh Goh Yeung (English title: Naked Killer (1992), in which a pair of lesbian assassins terrorize the male scumbags of Hong Kong before squaring off against a rival duo of lesbian hired killers.

Continue readingFate, Coincidence and Missed Opportunities

Most cinephiles remember the first time they saw a film by Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai. For me it was Ah Fei Jing Juen (English title: Days of Being Wild, 1990), which I rented on VHS from Blast-Off Video in Atlanta, Georgia. The owner, Sam Patton, encouraged me to watch it and it was a revelation, not like his usual recommendations which were more likely to be softcore exploitation films like Doris Wishman’s Deadly Weapons (1974) starring Chesty Morgan and her 73 inch bust or a bizarre obscurity like The Manipulator aka B.J. Lang Presents (1971) with Mickey Rooney at his most demented. What I saw was nothing like what I had seen coming out of the Hong Kong film industry at that time – mostly martial arts action films and kinetic crime thrillers such as John Woo’s The Killer (1989). No, Days of Being Wild is a lush, sensual cinematic poem, a visually innovative tale of unrequited longing, one-sided relationships and melancholy reflections on life as it was in Hong Kong in 1960, the year the movie takes place.

Continue readingGuilty Bystanders

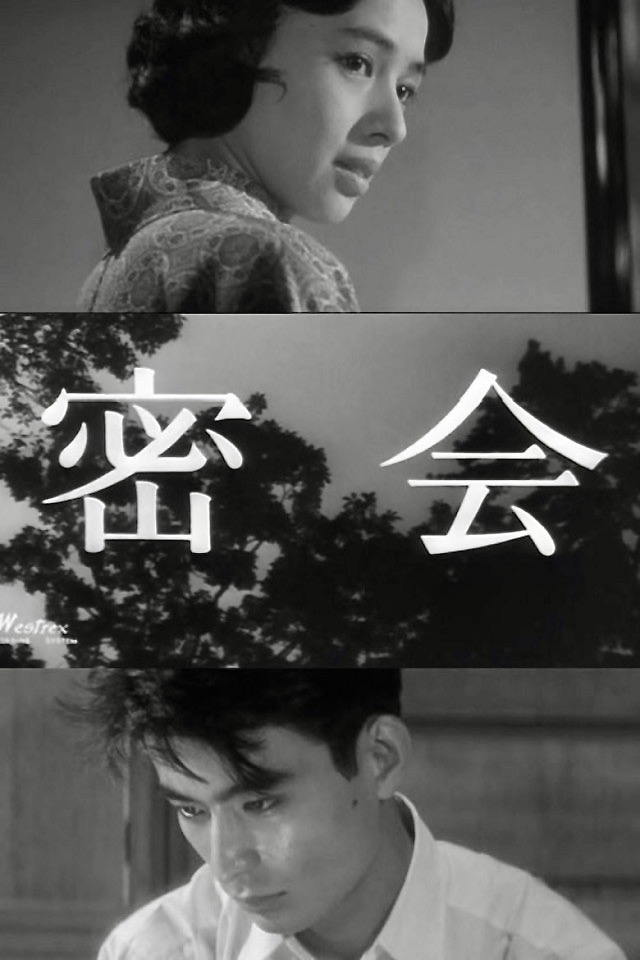

A young couple are enjoying a romantic rendezvous in a hidden grove at a city park at twilight. It turns out to be an illicit affair. The woman is the married wife of a law professor and her lover is one of his students. Their privacy is interrupted by the arrival of a speeding taxi that crashes into an embankment nearby. Inside the driver is seen struggling with the backseat occupant. It ends badly with the driver murdered and his body dragged into the bushes. The killer flees and the young couple are faced with a dilemma. Should they go to the police and risk exposing their affair or remain silent? This is the pressing issue that drives the narrative of The Assignation (Japanese title: Mikkai, 1959), directed by Ko Nakahira.

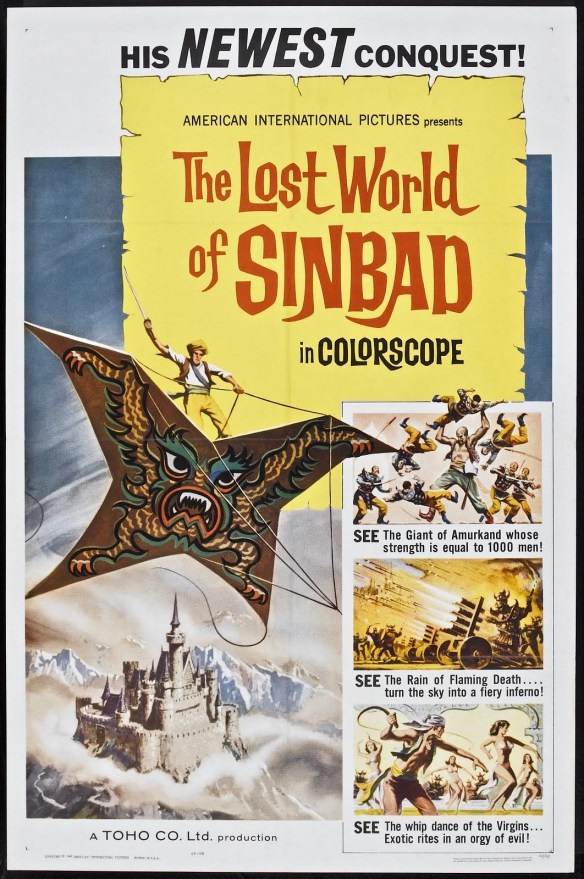

Continue readingThe Japanese Sinbad

Most moviegoers know Toshiro Mifune from his long and fruitful association with director Akira Kurosawa, most prominently Rashomon and The Seven Samurai, and a handful of major works from other directors in the Japanese cinema such as Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu (1952) and Hiroshi Inagaki’s Samurai Trilogy. But beyond his many period samurai roles and his more contemporary dramas and noirs (Drunken Angel, Stray Dog, The Bad Sleep Well), Mifune was much more than an international art house darling and award winning actor. He was a popular star and a product of the Japanese studio system just as Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy were creations of the Hollywood studio system. Like those two screen icons, Mifune also had his share of genre programmers and lowbrow general audience entertainments but The Lost World of Sinbad aka Samurai Pirate aka (1963) is one of his more enjoyable and eccentric efforts. Continue reading

Most moviegoers know Toshiro Mifune from his long and fruitful association with director Akira Kurosawa, most prominently Rashomon and The Seven Samurai, and a handful of major works from other directors in the Japanese cinema such as Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu (1952) and Hiroshi Inagaki’s Samurai Trilogy. But beyond his many period samurai roles and his more contemporary dramas and noirs (Drunken Angel, Stray Dog, The Bad Sleep Well), Mifune was much more than an international art house darling and award winning actor. He was a popular star and a product of the Japanese studio system just as Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy were creations of the Hollywood studio system. Like those two screen icons, Mifune also had his share of genre programmers and lowbrow general audience entertainments but The Lost World of Sinbad aka Samurai Pirate aka (1963) is one of his more enjoyable and eccentric efforts. Continue reading