You may have heard of the term Kirlian. It is usually associated with photography and refers to a process where an image is created by applying a high-frequency electric field to a living object. The result captures a pattern of luminescence which is recorded on photographic film and represents a life force or energy field surrounding the living object. The concept has never been embraced by the scientific community but became popular in parapsychology and paranormal research in the mid-fifties. It even inspired a low-budget indie art house mystery called The Kirlian Witness (1978), directed by Jonathan Sarno, about a murder that is solved by a houseplant that witnessed the crime. Yet, even before this obscure, rarely seen feature, the concept of Kirlian energy provided an explanation for the behavior of the insane protagonist of Psychic Killer (1975 aka The Kirlian Force aka The Kirlian Effect), a trashy but consistently entertaining horror thriller featuring a cast of familiar Hollywood character actors and Jim Hutton as the unlikely title character in his final theatrical feature. If you’re looking for an offbeat, non-traditional horror movie for your Halloween viewing, this is a good choice.

Continue readingMonthly Archives: October 2024

Movie Title Hall of Fame: The Sublime, the Weird and the Ridiculous

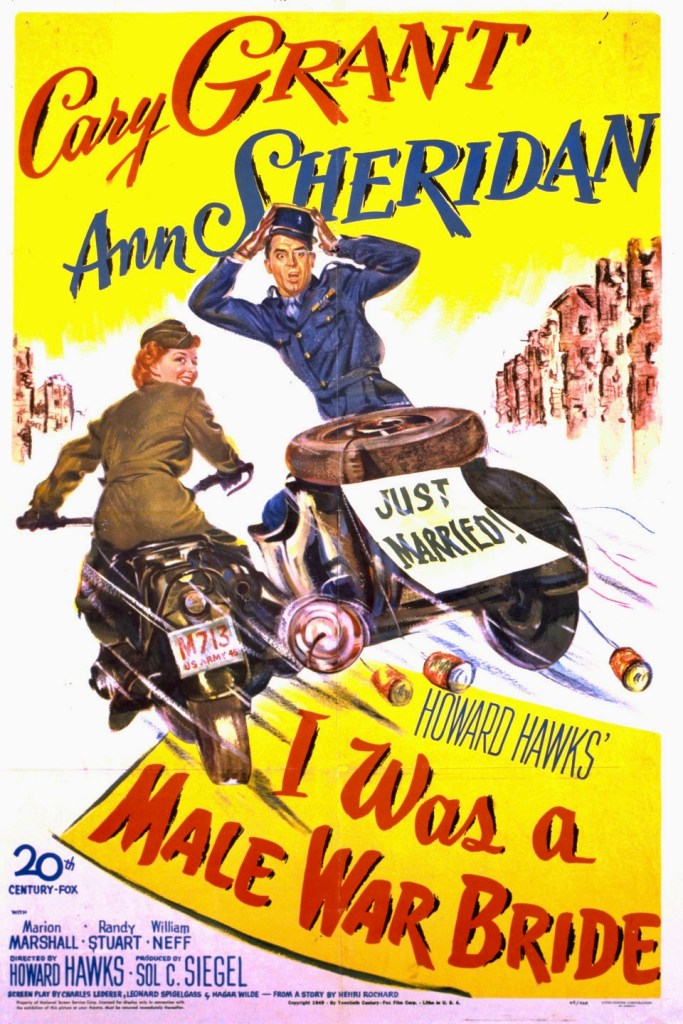

There are certain movie titles that make you pause and consider the mystery, allure or absurdity of their meaning. They can promise so much and deliver so little like Billy the Kid vs. Dracula (1966) or She Gods of Tiger Reef (1958). Or they can overdeliver on their promise to an astonished but grateful audience as in Russ Meyer’s infamous Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965). They can also mislead and confound you with wording so vague or fanciful that you have no earthly idea what it’s about as in Lord Love a Duck (1966), The Day the Fish Came Out (1967), or All the Fine Young Cannibals (1960), which inspired the name of the Brit pop trio that had a hit with “She Drives Me Crazy.” Then there are those completely frank and unambiguous titles that reveal the pure essence of the film in a no-nonsense manner – Teenagers from Outer Space (1959) and I Was a Male War Bride (1940). Or titles that are so much fun to say that you simply love saying them out loud just to hear the sound of them rolling off your tongue like Rat Pfink a Boo Boo (1966) or Puddin’ Head (1941).

Continue readingLife in Transition

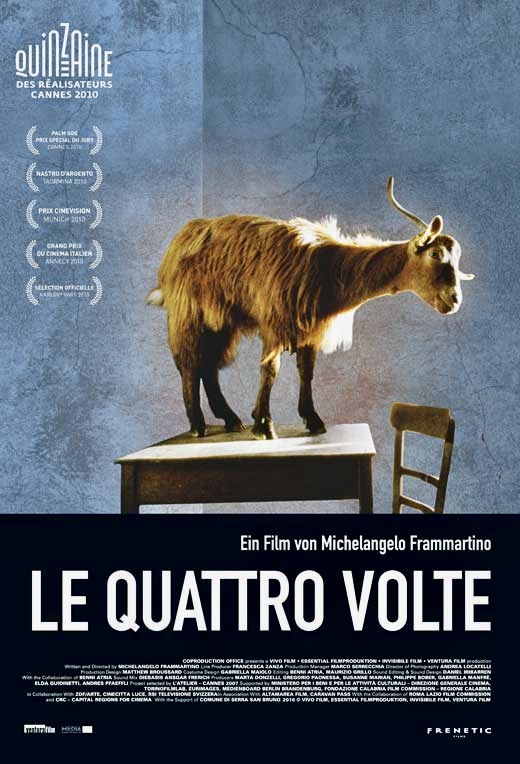

Smoke fills the screen and drifts toward the sky. We see black earth that is steaming and could be cooling lava. Then we notice small holes punched into the dark topography where smoke is being released. A wide shot reveals that we are looking at a mound of charred material that is being raked by a worker at the top of the heap. Where are we and what are we looking at? Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte (2010), which roughly translates as The Four Times, is an immersive but often disorienting portrait of life in the village of Caulonia, Italy, which often requires the viewer to make sense of a visual detail or local ritual without a frame of reference. This is not detrimental, however, to the film’s exploratory narrative but one which is enriched by a sense of mystery and wonder.

Continue readingM.R. James Times Two

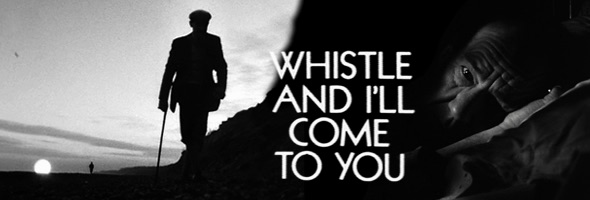

Montague Rhodes James, better known as M.R. James (1862-1936), was a celebrated author and medievalist scholar from the U.K. who is best known today for his many ghost stories. Horror film buffs in the U.S. were first exposed to his work when director Jacques Tourneur adapted his short story “Casting the Runes” for the 1957 film Curse of the Demon (it was titled Night of the Demon in the U.K.). To date, that still reminds the most famous M.R. James theatrical feature but that doesn’t mean the author’s work hasn’t been adapted in other memorable renditions, most of them as made-for-television productions from England. One of the most famous is James’s short story, “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad” from 1904, which has been filmed twice by the BBC, one in 1968 entitled Whistle and I’ll Come to You starring Michael Horden and a remake from 2010 with the same title that featured John Hurt.

Continue readingThe Rip Van Winkle Syndrome

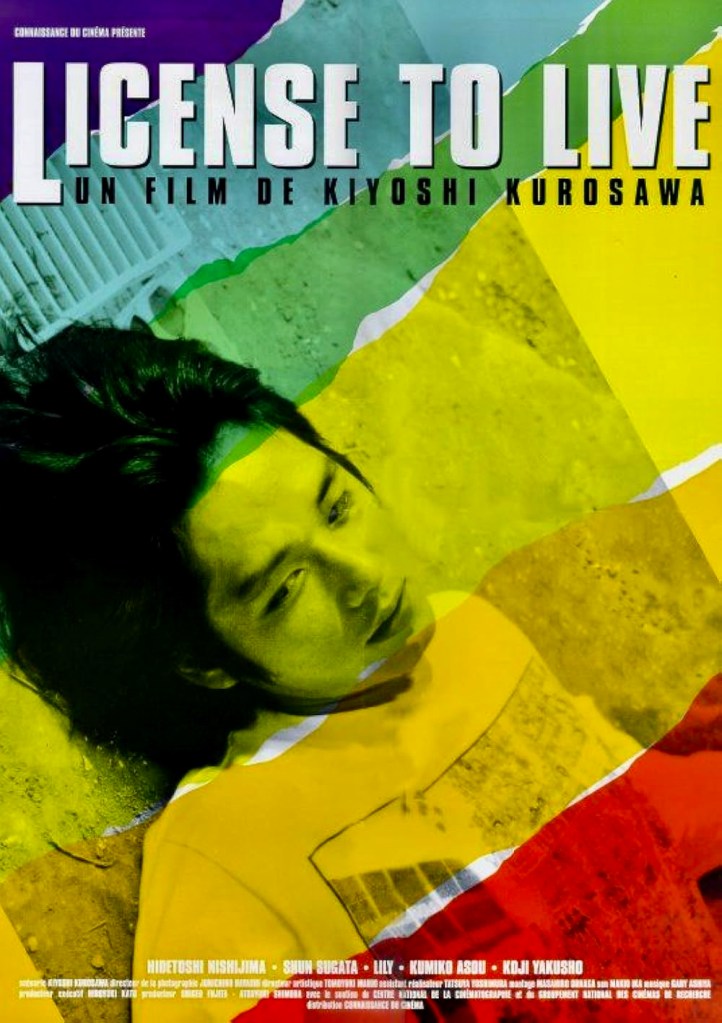

Yutaka Yoshii (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is a twenty-four-year-old man who suddenly wakes up from a coma after ten years and has to readjust to a new world. This is the basic set-up of Ningen Gokaku (English title: License to Live, 1998), a decidedly change-of-pace effort from Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who is better known for creepy occult/psychological thrillers like Sweet Home (1989), Cure (1997) and Pulse (2001). You can only imagine what an American film studio would do with this simple concept – it would either become a rom-com like While You Were Sleeping (1995) or a horror flick such as The Dead Zone (1983) – but Kurosawa takes an approach that probably surprised even his most fervid fans. License to Live turns out to be a low-key, observational series of vignettes that slowly culminate in a moving meditation on the things that make the life of a human being worth living.

Continue readingHucksters, Phonies and Rubberneckers

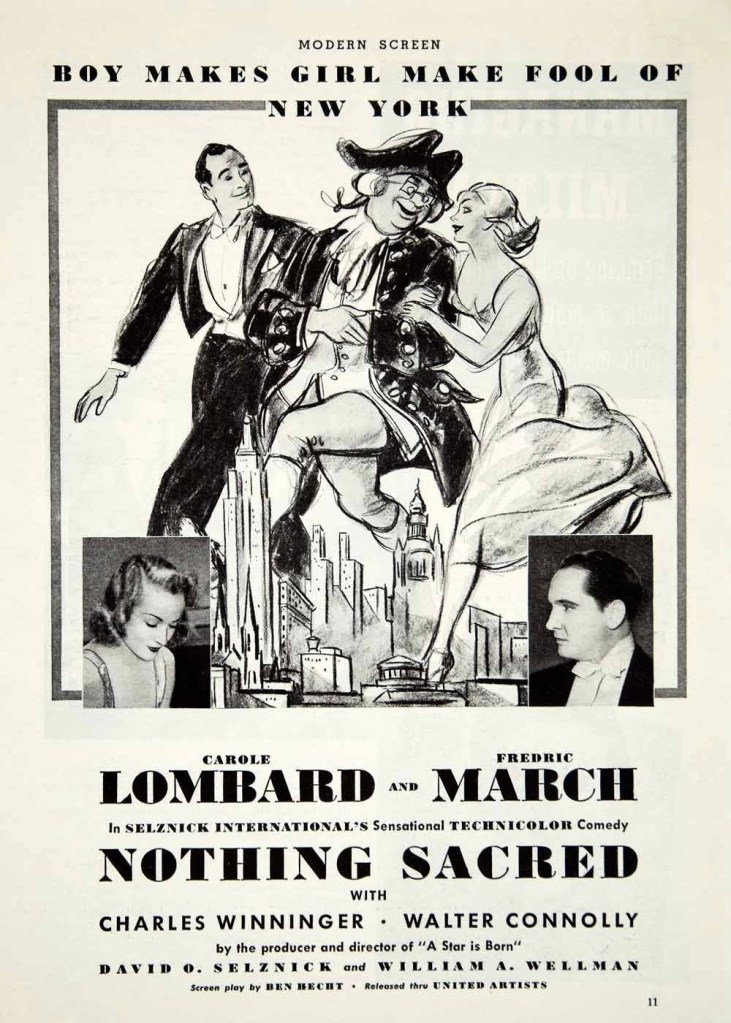

Nothing Sacred (1937) is a key film in that short-lived genre known as ‘the screwball comedy,” a unique Hollywood creation that flourished between 1933 and 1940. Distinguished by its eccentric characters, irreverent humor, and breakneck pacing, these films usually featured privileged but irresponsible characters running amok against the backdrop of the Great Depression when society was in turmoil. But while the idle rich were mercilessly lampooned in the most popular screwball comedy of the previous year – My Man Godfrey (1936) – the whole human race gets dished in Nothing Sacred, from the newspaper industry to a public that enjoys reading sob stories about someone else’s misfortune.

Continue readingPack Mentality

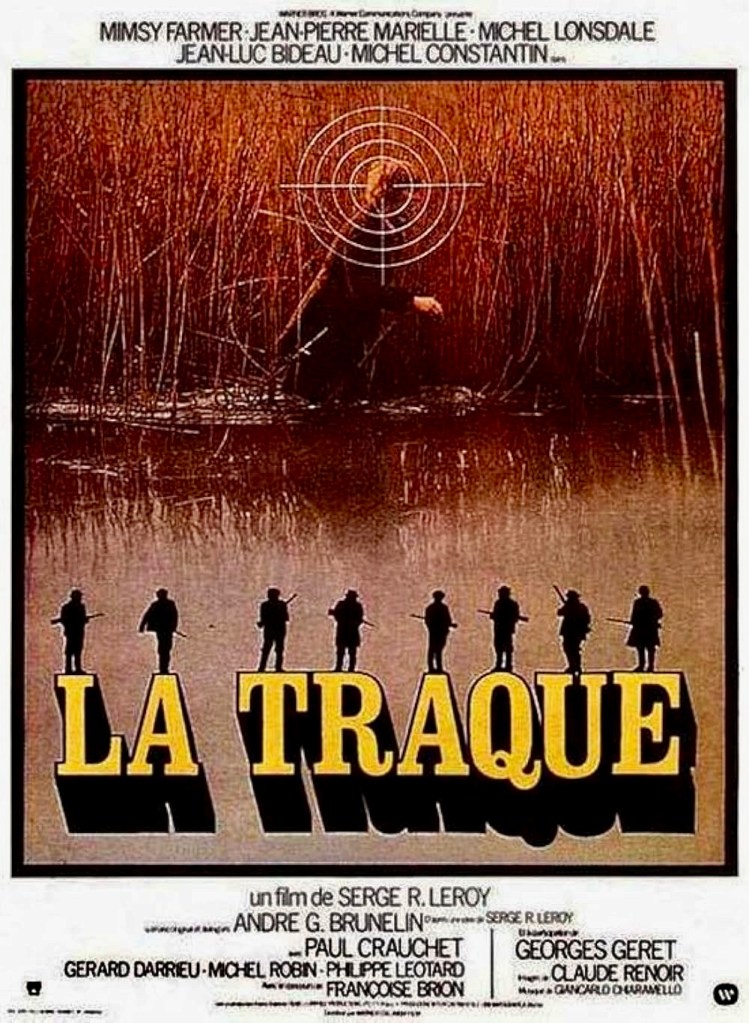

What happens when you get a bunch of men together, some of them armed with flasks of brandy or whiskey, give them guns and set them loose in the forest? It sounds like a lethal combination but it doesn’t have to be and rarely is in the world of experienced outdoorsmen. At the movies, though, it’s a different story as witnessed by so many thrillers about hunting parties and their targets. Certainly the many film adaptations of Richard Connell’s short story The Most Dangerous Game is a famous example but there are also variations such as armed officers hunting a prisoner (Antonio Isasi-Isasmendi’s A Dog Called Vengeance, 1977), men hunting each other (Carlos Saura’s The Hunt, 1967), men and women stalking each other (Elio Petri’s The 10th Victim, 1965) or men hunting women (the Australian revenge flick Fair Game, 1986). La Traque (aka The Track), a French film by Sergio Leroy, fits into the last category, but it is not a predictable genre entertainment, a satire or a blatant exploitation film.

Continue reading