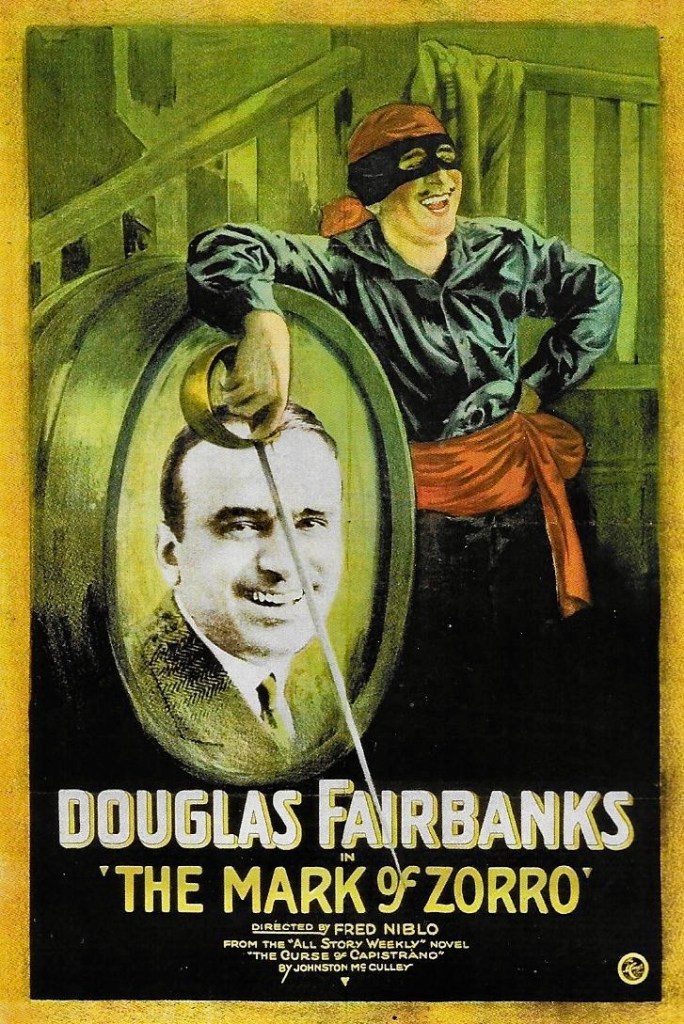

It is a well known fact that Douglas Fairbanks was one of the first superstars of the silent era but he first became famous as a leading man in romantic comedies such as Wild and Woolly (1917) and Reaching for the Moon (1917). In the aftermath of World War I, audiences had grown bored with the cheerful, boy-meets-girl formula that had made Fairbanks a popular screen idol so the star decided to try a different tactic. A short story by Johnston McCulley, “The Curse of Capistrano,” had appeared in the pulp magazine, All-Story Weekly, and he decided to read it during a long train trip from New York to Los Angeles. This was unusual in itself since Fairbanks did not like to read (and that included his movie scripts) but actress Mary Pickford encouraged him to read the serial and McCulley’s story became his next project. It was first called The Curse of Capistrano, which was then changed to The Black Fox and finally released as The Mark of Zorro in 1920.

Continue readingAuthor Archives: JStafford

Extraordinary Encounters on the Trans-Siberian Express

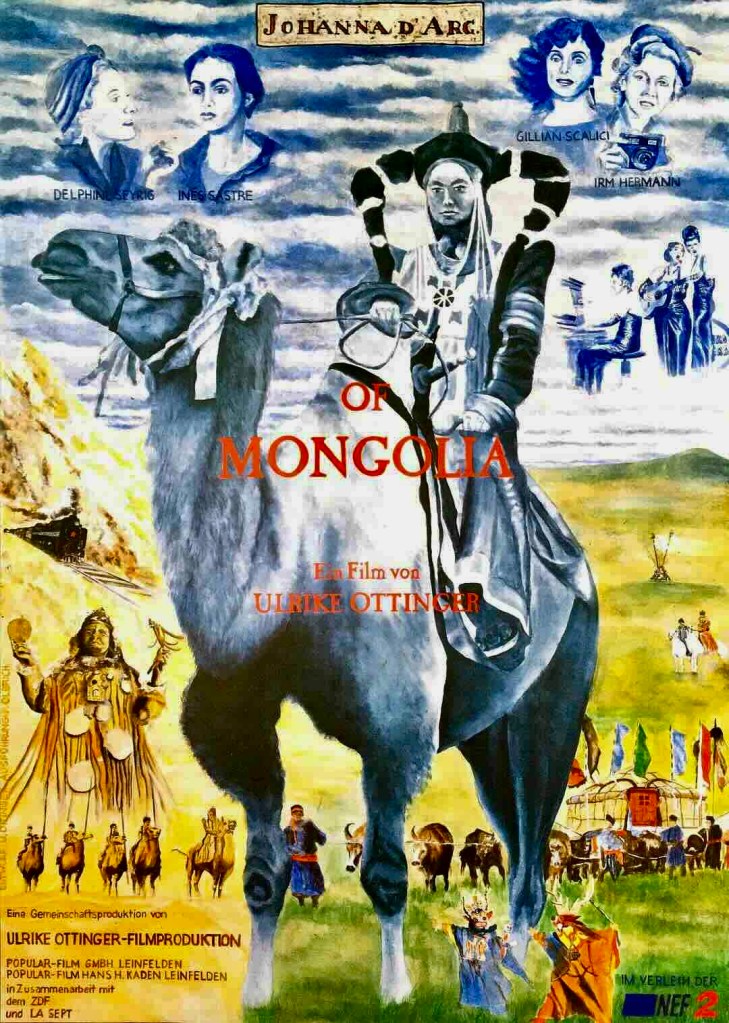

Movies that take place on trains constitute a film genre of their own and there have been plenty of great ones over the years – The General (1926), The Lady Vanishes (1938), The Narrow Margin (1952), Snowpiercer (2013) – but I can safely say that Johanna D’Arc of Mongolia (English title: Joan of Arc of Mongolia, 1989), directed by Ulrike Ottinger, is the most unusual one ever made. Although it embraces the idea that travel can be a life-changing experience for everyone, Ottinger puts her own personal spin on this by addressing ideas about gender, history, personal empowerment and cultural traditions through a smash-up of popular genres. These include musical theater, campy soap operas, widescreen epics and ethnographic documentaries. It might sound like either a complete goof or pretentious nonsense (some detractors claim both) but it works as a one-of-a-kind hybrid, informed by Ottinger’s insights into human behavior and her own directorial eccentricities.

Continue readingThe Free Cinema Shorts of Lindsay Anderson

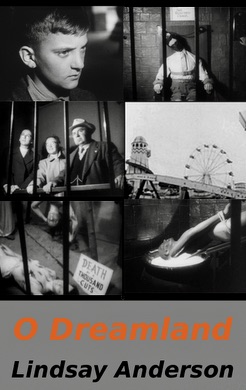

The 1960s might be seen as the decade that ushered in a significant number of game changing film movements such as the Czech New Wave, Cinema Verite and New German Cinema but the 1950s shouldn’t be overlooked for inspiring the birth of the Nouvelle Vague in France and the self-reflective ‘kitchen sink’ realism trend in England. One of the most influential but short lived film developments during this period was the Free Cinema movement, which flourished between 1956 and 1959 in the U.K.. It rejected the conservativism and class bound traditions of commercial filmmaking as well as the didactic approach to documentaries made famous by Scottish director John Griegson (Song of Ceylon [1934], Night Mail [1936]]. Instead, Free Cinema was dedicated to making personal films that expressed the opinion and artistic vision of their directors despite limited budgets and semi-amateur conditions (most of the movies were shot with a 16mm Bolex camera). Karel Reisz, Alain Tanner, Claude Goretta, Tony Richardson and Lindsay Anderson were among the leaders of the Free Cinema group but Anderson, in particular, created some of the movement’s most significant work, including Wakefield Express (1952), O Dreamland (1953), Thursday’s Children (1955) and Every Day Except Christmas (1957). Continue reading

The Scumbag Annihilator

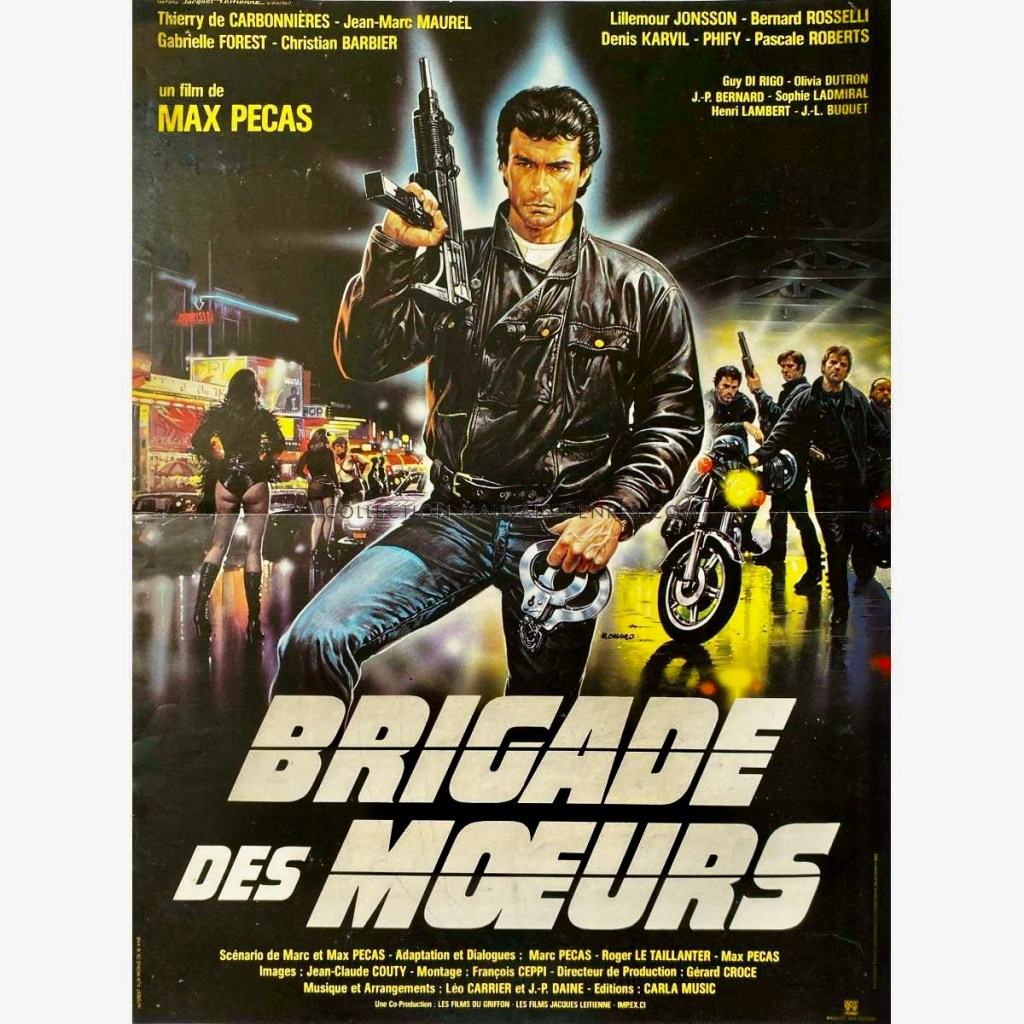

You may not know the name Max Pecas, but along with Jose Benazeraf and Jean Rollin, he was one of the more famous French directors of softcore erotic/exploitation films of the 60s and 70s. Two of his earliest films helped launch the film career of German sexpot Elke Sommer. De Quoi tut e Meles Daniela! (English title: Daniella by Night, 1961) was an espionage melodrama highlighted by some brief nudity of the lead actress and Douce Violence (English title: Sweet Violence, 1962) depicted jaded teenagers going wild on the Riviera in a style imitative of the New Wave films of that era. Pecas later moved on to more explicit adult fare in films like The Sensuous Teenager aka I Am a Nymphomaniac! (1971) and I Am Frigid…Why? (1972) before turning out some genuine hardcore X-rated features such as Felicia (1975) and Sweet Taste of Honey (1976), which were also released in edited R-rated versions. Despite low budgets, his films often had a classy veneer with gorgeous actresses but critics routinely derided his work despite their popularity with grindhouse audiences. Then toward the end of his career, Pecas surprised everyone with a dynamic but violent crime thriller set in the seedy underworld of Paris – Brigade des Moeurs (English title: Brigade of Death aka Death Squad, 1985) – which was closer to the gritty style of an Abel Ferrara film like Ms. 45 (1981) or Fear City (1984).

Continue readingRobot Riot

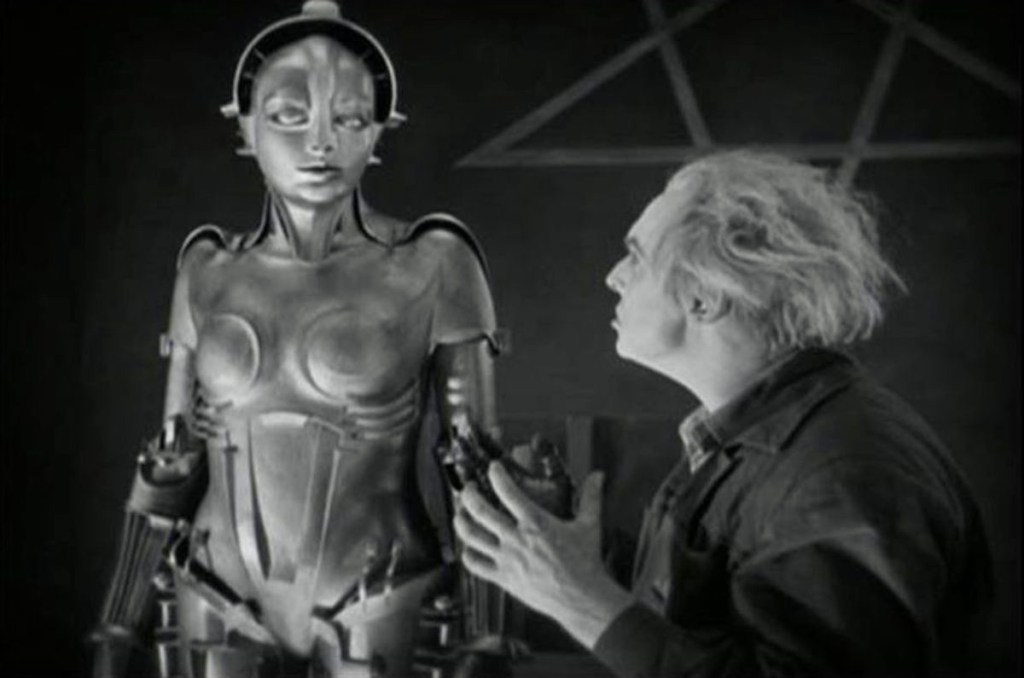

When I hear the word robot, I immediately think of Robby, the delightful and super intelligent creation of Dr. Morbius in Forbidden Planet (1956), one of the landmark sci-fi movies of the fifties. His barrel-shaped torso and high-tech design were so popular that he inspired countless toy collectibles for kids but he was a benign example of the form. For the most part, robots in science fiction films are generally viewed as a threat (see 1954’s Target Earth, 1957’s Kronos or 1958’s The Colossus of New York for examples). That was certainly the case in one of the first and most famous depictions of a robot – Fritz Lang’s silent sci-fi masterpiece, Metropolis (1927). Designed as a doppelganger for Maria, a revered female leader of factory workers, the false Maria preaches revolution to the working class, resulting in the sort of chaos that threatens to topple civilization (The False Maria’s robotic metal frame is disguised beneath her human façade).

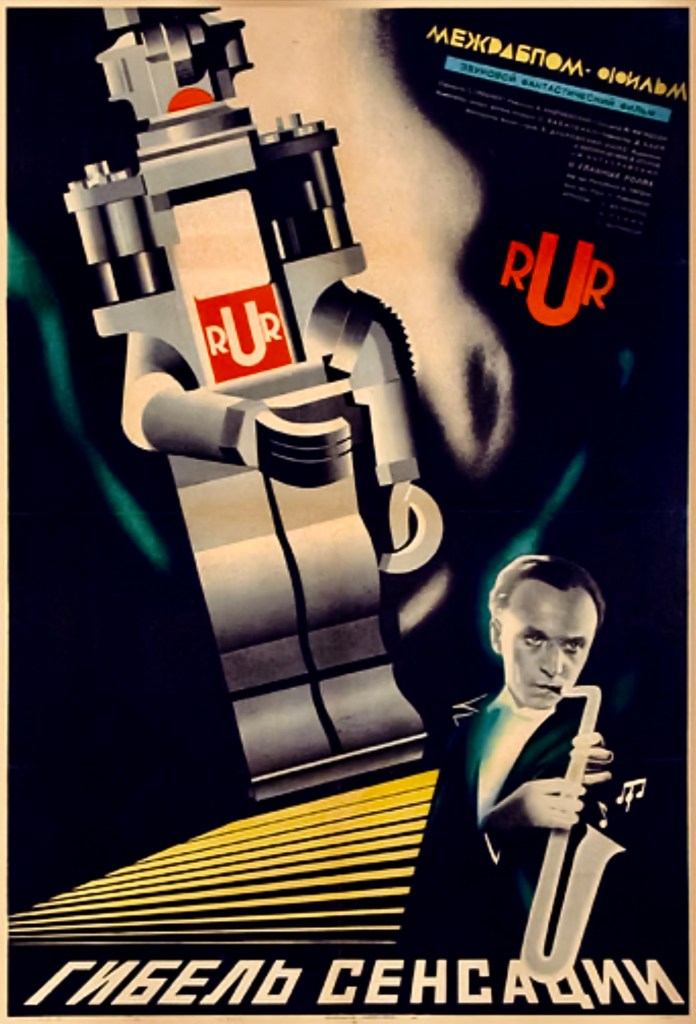

Eight years later, robots were again viewed as a danger to the human race in the Russian film, Gibel Sensatsii (English title: Loss of Feeling aka Loss of Sensation aka Robots of Ripl, 1935) although these looked more like early prototypes of the walking oil can-shaped automatons seen in later serials like The Phantom Empire (1936) and The Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940).

Continue readingAnatomy of a Marriage

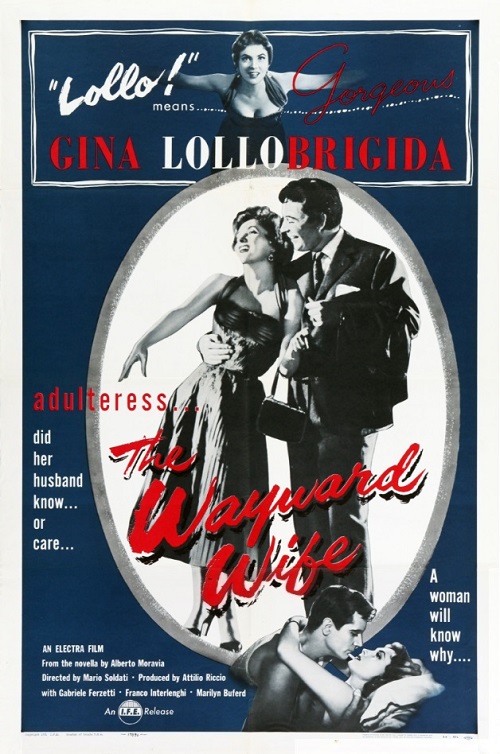

There is little doubt that Gina Lollobrigida’s rise to fame in the post-WW2 years was attributed to her beauty and sex appeal but there was another reason she achieved international recognition – she was a gifted actress who was magnetic and believable in any film genre. In fact, some of her best work is evident in a few key films of the early 1950s but is often overshadowed by the glossy Hollywood productions she made during her peak years such as Solomon and Sheba (1959), Never So Few (1959) and Come September (1961). Rene Clair’s romantic fantasy Beauties of the Night (1952) is generally credited as Lollobrigida’s breakthrough film and Luigi Comencini’s Bread, Love and Dreams (1953) brought her international acclaim as an actress (She was nominated for Best Foreign Actress by BAFTA and won Best Actress from the Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists). But she had already proven herself as someone who could convincingly move from war drama (Achtung! Banditi!, 1951) to costume swashbuckler (Fanfare La Tulip, 1952) to sex farce (Wife for a Night, 1952) and La Provinciale (English title: The Wayward Wife, 1953), directed by Mario Soldati, is an impressive early dramatic showcase for Lollobrigida that is almost forgotten today.

Continue readingLove Potions and Ancestral Curses

Want to know what great acting is? It’s when two actors who loathe each other in real life have to perform a convincing love scene on film. And watching I Married a Witch (1942) starring Veronica Lake and Fredric March, you’d never guess that this romantic duo feuded constantly during the making of the film. On the surface, I Married a Witch is a tale of the supernatural, played for laughs, and uses its premise to poke fun at American politics, the institution of marriage, and New England’s puritan ancestors.

Continue readingRoll with the Punches

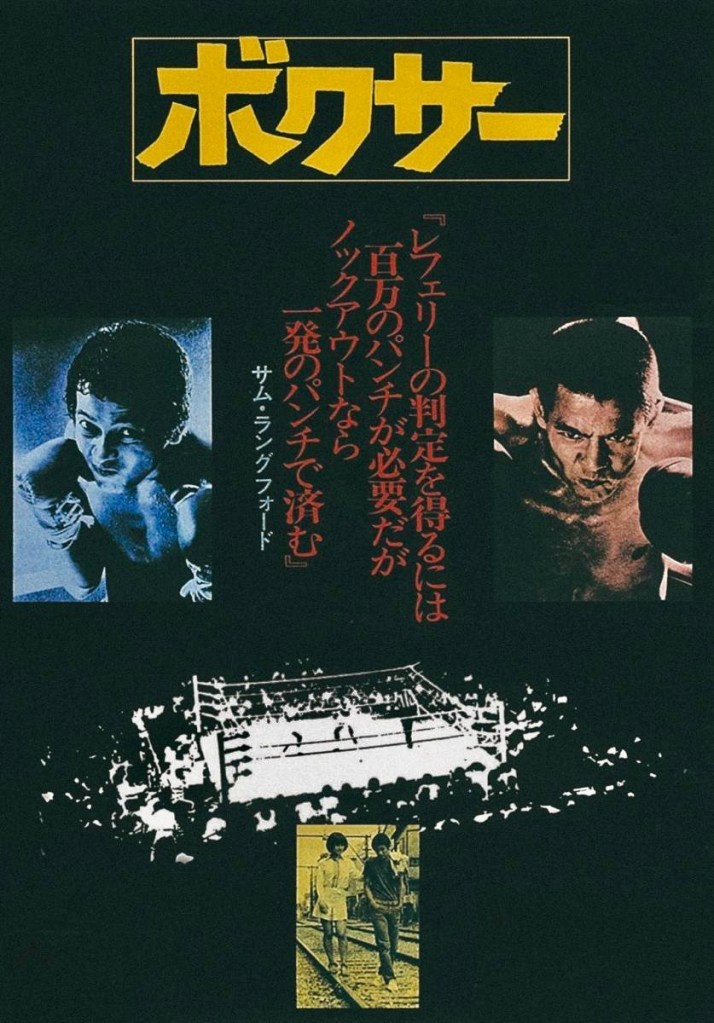

Movies about boxers often seem to break down into four categories; the most popular are the ones where the underdog fighter overcomes all odds to become a champion (Rocky [1976], Million Dollar Baby [2004], Cinderella Man [2005]). Then there are true-life biopics like Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), Raging Bull (1980) and Ali (2001), downbeat character portraits of boxers past their prime (Requiem for a Heavyweight [1962], Fat City [1972]) and noir dramas that highlight the corrupt aspects of the profession like The Set-Up (1949) or The Harder They Fall (1956). Bokusa (English title: The Boxer (1977), a Japanese film directed by Shuji Terayama, has elements of some of the above but it is decidedly different from any American film in the boxing genre.

Continue readingLeprechauns, Pookas and Banshees

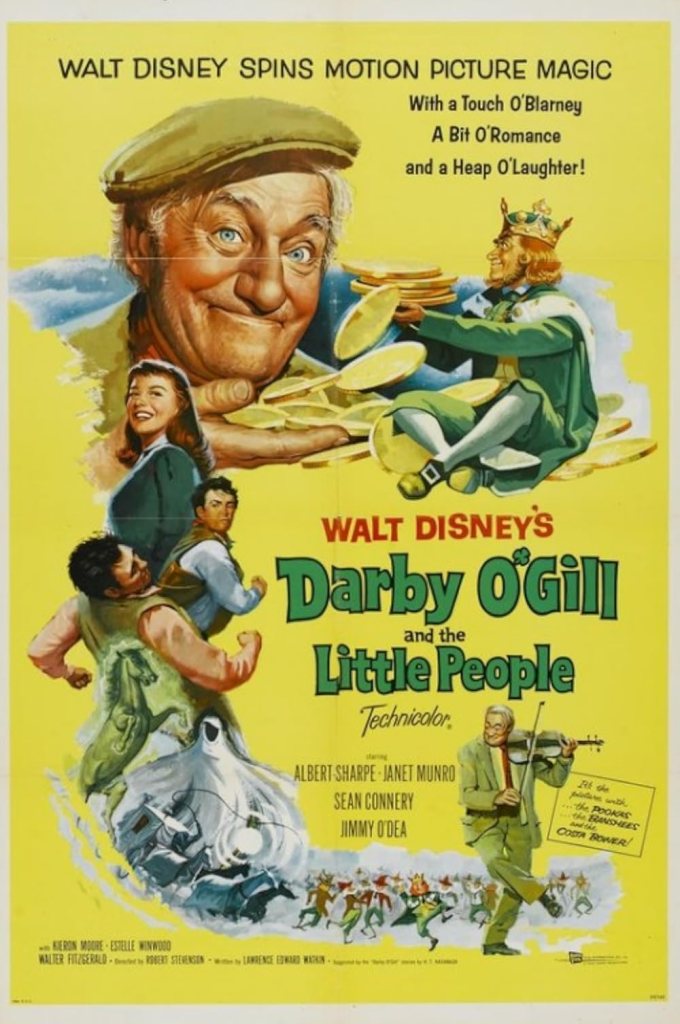

When you think of the many accomplishments of animation pioneer and studio mogul Walt Disney, producing horror films is not one of them. At the same time, several Walt Disney films have featured horrific moments that made strong impressions and scared children such as the boys-into-donkeys transformation scene in Pinocchio (1940) or the fire-breathing dragon at the climax of Sleeping Beauty (1959). A few Disney productions even flirted with the supernatural and creepy folk tales such as The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1949) and Dr. Syn (1964) with its title character disguised as a demonic-looking scarecrow who haunts the marshes at night. Nothing, however, can top Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959) when it comes to merging the ordinary with the fantastic. The film plunges the viewer into a fairytale Ireland where magical and terrifying things occur and some scenes could actually give the kiddies nightmares, making this my favorite Disney live-action film.

Continue readingArtists on the Battlefield

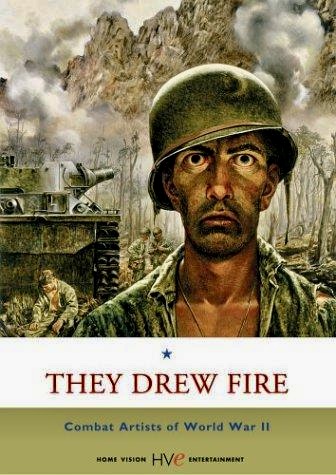

Originally produced for Oregon Public Television in 1999 and released on home video in 2000, They Drew Fire: Combat Artists of World War II is a fascinating and informative documentary on a little-known aspect of World War II; namely, the role artists and illustrators played in America’s war effort. Often assigned to the front lines where they frequently found themselves in life-threatening combat situations, these young men stood apart from their fellow soldiers in one regard; they came equipped with sketch pads, paints, canvases, brushes and other art supplies. Armed with these tools of the trade, this specialized group transformed their experiences into powerful works of art which revealed the true horrors of the battlefield, many of which were showcased in such widely-read publications as Life magazine.

Continue reading