“Be careful what you wish for” is one of those popular expressions that offers cautionary advice for those who want something too desperately. And it has been illustrated repeatedly in literature and movies from timeless folk tales like Faust and The Golem to more recent efforts like Little Otik (2000), Czech filmmaker Jan Svankmajer’s take on Otesanek, a 19th century fairy tale by Karel Jaromir Erben. Svankmajer updates the tale about a childless couple and their substitute baby to contemporary times but also manages to weave in some of his favorite obsessions and thematic concerns (food, cannibalism, human fears) into a darkly funny but nightmarish portrait of parenthood and child rearing. Despite its stature as a fable, Little Otik is certainly not for children and probably not the best viewing option for expectant mothers either.

Continue readingTag Archives: Eraserhead

Autobiography of a Sleepwalker

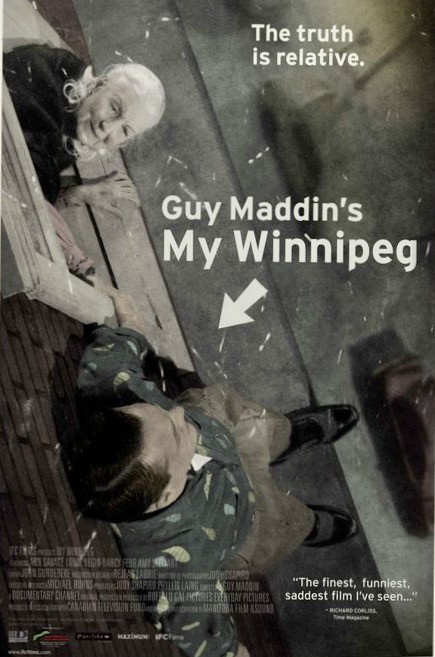

How does a filmmaker begin to craft an autobiographical film of his or her own life? Many renowned directors have tackled it but usually by using a fictionalized version of themselves under a different name though many of the incidents depicted are true. Francois Truffaut did it with The 400 Blows (1959) as did George Lucas with American Graffitti (1973) and Sam Fuller in The Big Red One (1980). Even more recently Steven Spielberg re-imagined his childhood and teenage years in The Fabelmans (2022). But no one has ever made a more personal and dreamlike meditation on their roots than what Guy Maddin accomplishes with My Winnipeg (2007), which is set in the city where the Canadian director was born and resided for much of his life. Narrated by Maddin in a voice that sounds half asleep, half awake, our somnambulistic guide creates his own mythology about himself, his family and his home town that is utterly unique. Plus, his narrator approach is totally fitting for a city that allegedly has more sleepwalkers among its residents than any other major city.

Continue readingThe Haunted Cornea

When Nobuhiko Obayashi’s Hausu (English title: House) opened in Japan in 1977, it proved to be a surprise hit with audiences but not Japanese film critics and it didn’t attract any attention in the U.S. until it was rediscovered in 2009 as possibly the weirdest WFT cult movie since El Topo (1970), Eraserhead (1977) or Repo Man (1984). Originally intended for teenagers, particularly girls, House pits a bunch of young female schoolgirls against a demonic entity and the result is a frenzy of nightmarish images including flying decapitated heads, a cannibalistic piano, a satanic cat, and laughing watermelons to name a few. Obayashi’s subsequent film, Hitomi no naka no houmonsha (English title: The Visitor in the Eye, 1977) isn’t nearly as wild and raucous but it shares the same demented fairy tale ambiance of House and was overshadowed by its predecessor.

Continue readingIn the Kingdom of G

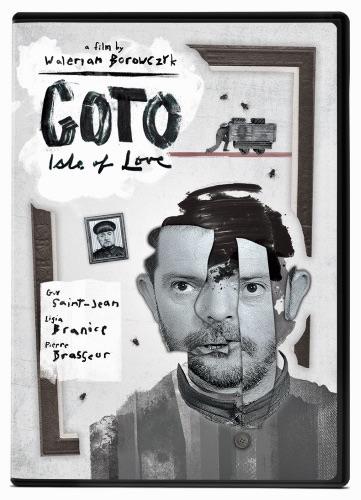

In the film world of the 20th century, there were not too many animators who made the transition to live action feature film directing. Certainly Frank Tashlin was one of the most famous, going from Porky Pig and Daffy Duck cartoon shorts to manic pop culture comedies like The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) and Hollywood or Bust (1956). Another rare exception was George Pal, who became famous for his Puppetoon shorts for Paramount before establishing himself as a director of fantasy features such as Tom Thumb (1958) and The Time Machine (1960). It is far easier to name more contemporary filmmakers like Terry Gilliam, Tim Burton and Brad Bird, all of whom graduated from cartoons to live-action features successfully. The above are all artists who worked in the commercial cinema but, if you are talking about art cinema, the list is much smaller and Polish animator Walerian Borowczyk should be in the top slot. Goto, Island of Love (1969, Polish title: Goto, I’ile d’amour), his feature film debut, is a fascinating achievement that successfully brings the avant-garde sensibilities of his animated shorts to a live action feature.

Continue readingDown on the Farm

The exploitation of animals in society and the food industry, in particular, is a problem most consumers don’t want to face or consider but a protest movement against the practice is growing larger every year thanks to hard-hitting documentaries like Myriam Alaux & Victor Schonfeld’s The Animals Film (1981), Shaun Monson’s Earthlings (2005), and Robert Keener’s Food, Inc. (2008) – all of which expose the mass production of animals for food. Tackling the same subject but taking a completely different approach to it is Gunda (2020) by Russian filmmaker Viktor Kossakovsky, which dispenses with voice over narration, a music score or any on-camera interviewees. Instead, it focuses a sow named Gunda and her piglets, a few chickens and some cows over a brief period on a farm before they become “products.” The concept may sound uninteresting and tedious but Gunda is not really a traditional documentary by any stretch of the imagination and the result is a completely engrossing, emotional drama with animals as its main characters.