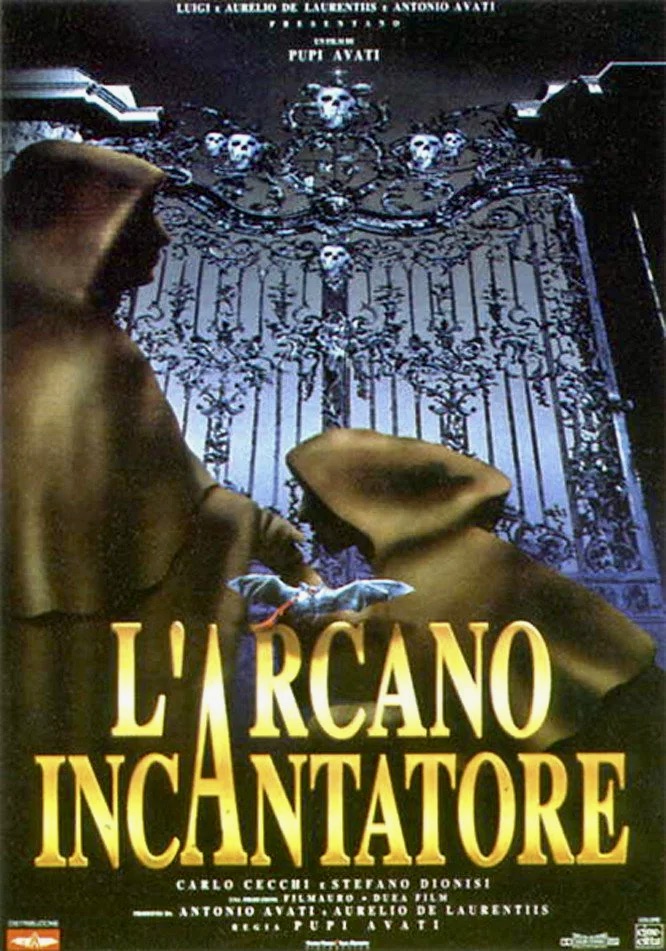

Ever since the international box office success of The Exorcist in 1973, horror films dealing with religion and priests have usually focused on demonic possession. This trend even continues today as witnessed by the release of The Pope’s Exorcist (2023) and The Exorcism (2024), both starring Russell Crowe. A refreshingly different approach to this often formulaic subgenre is L’Arcano Incantatore (English title: The Arcane Sorcerer), a sadly overlooked but richly atmospheric period thriller from Italian director Pupi Avati, which premiered in 1996 but never received an official theatrical release in the U.S.

Continue reading