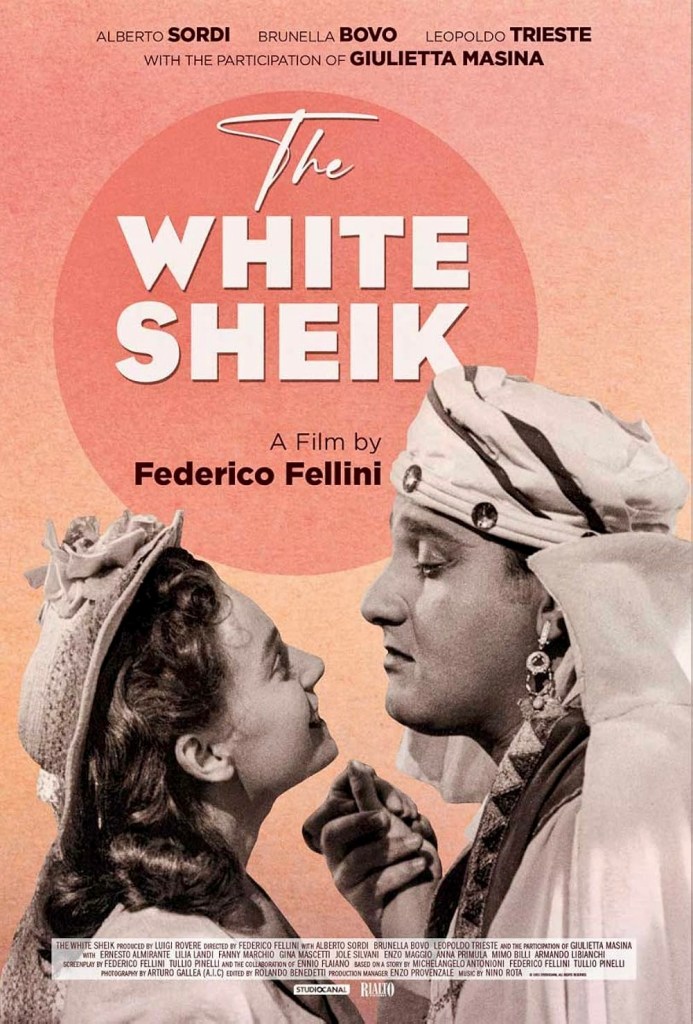

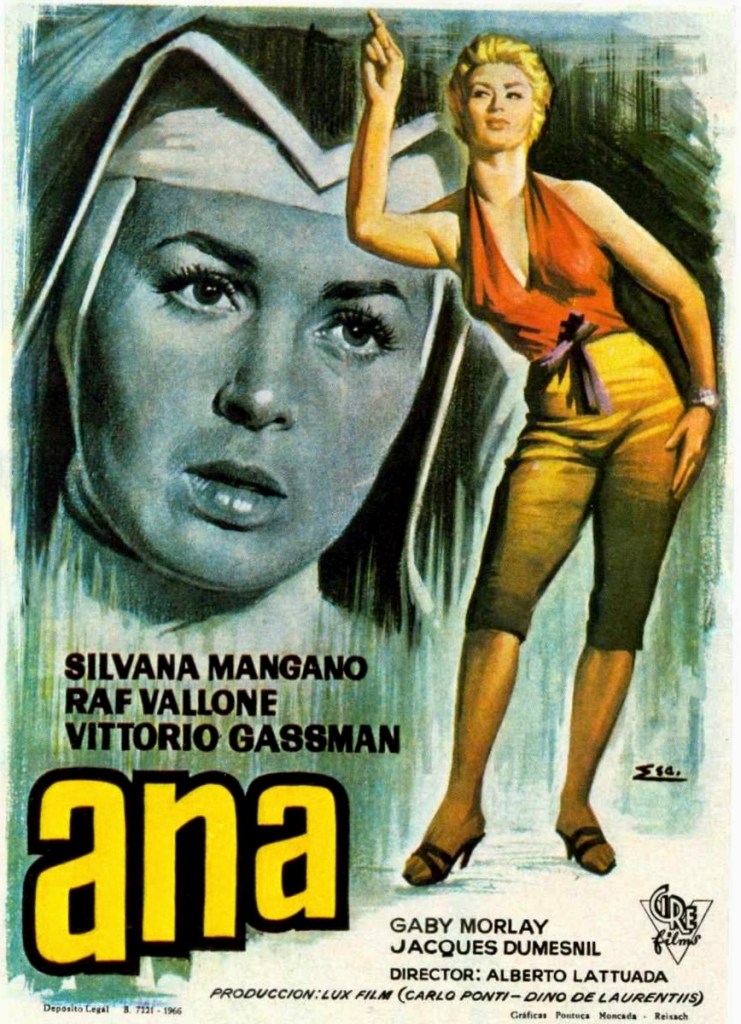

He was a prominent and commercially successful director for most of his career but Alberto Lattuada is often overlooked when film scholars discuss the important Italian filmmakers of the postwar era. Part of the problem was that he was hard to pigeonhole due to his eclectic filmography yet he always seemed to have his finger on the pulse of Italian popular culture. And his films reflected the changing times and interests of his generation from the birth of the neorealism movement [Il Bandito aka The Bandit (1946), Senza Pieta aka Without Pity (1948)] to literary adaptations [Il Mulino del Po aka The Mill on the Po (1949), La Steppe aka The Steppe (1962)] to popular entertainments focused on female protagonists like Guendalina (1957) featuring Jacqueline Sassard in her first starring role and Nastassja Kinski in Cosi come sei aka Stay as You Are (1978). Lattuada might be just a footnote in film history due to his collaboration with Federico Fellini on Luci del Varieta (English title: Variety Lights, 1950) but Italian audiences flocked to his films and they made his 1951 melodrama Anna starring Silvana Mangano (in the title role) into a major box office smash.

Continue reading