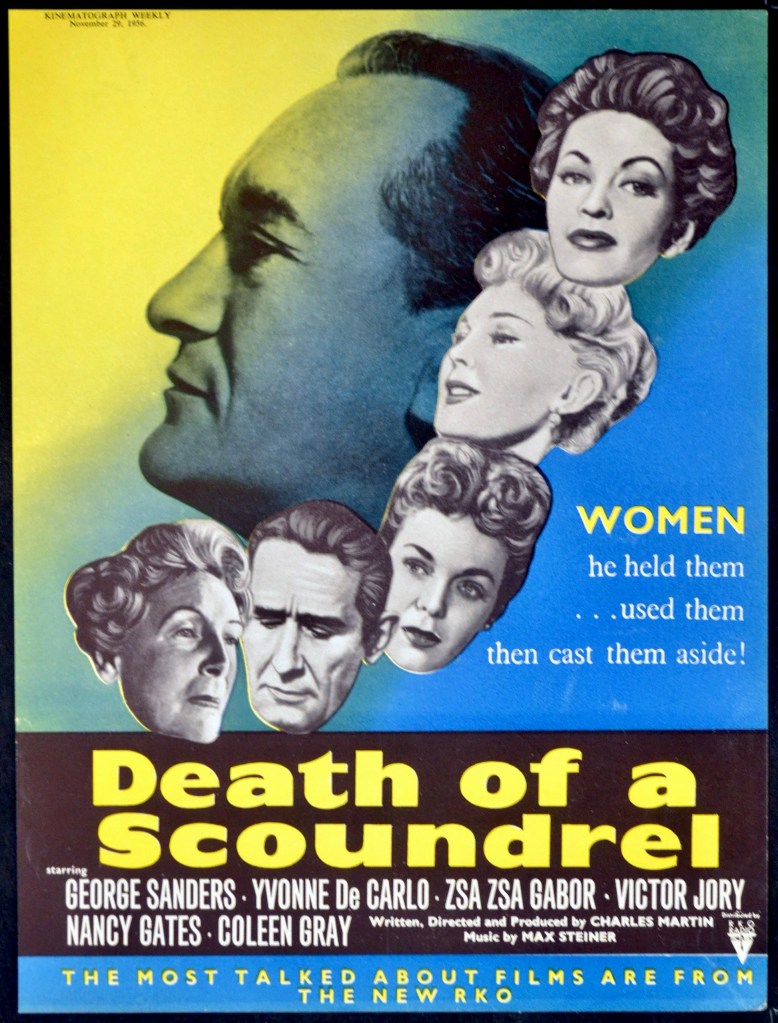

Imagine Citizen Kane (1941) on a miniscule budget with a much more ruthless and totally despicable protagonist and you have Death of a Scoundrel (1956), a contemporary take on The Rake’s Progress. Like the former film, it was shot on the RKO backlot and unfolds in a flashback structure, starting with Bridget Kelly (Yvonne De Carlo), personal assistant to self-made tycoon Clementi Sabourni (George Sanders), revealing to the police the circumstances that led to the millionaire’s murder. “He was the most hated man on earth,” she declares, “But he could have been one of the great men in history. He was a genius.”

Continue readingMonthly Archives: January 2026

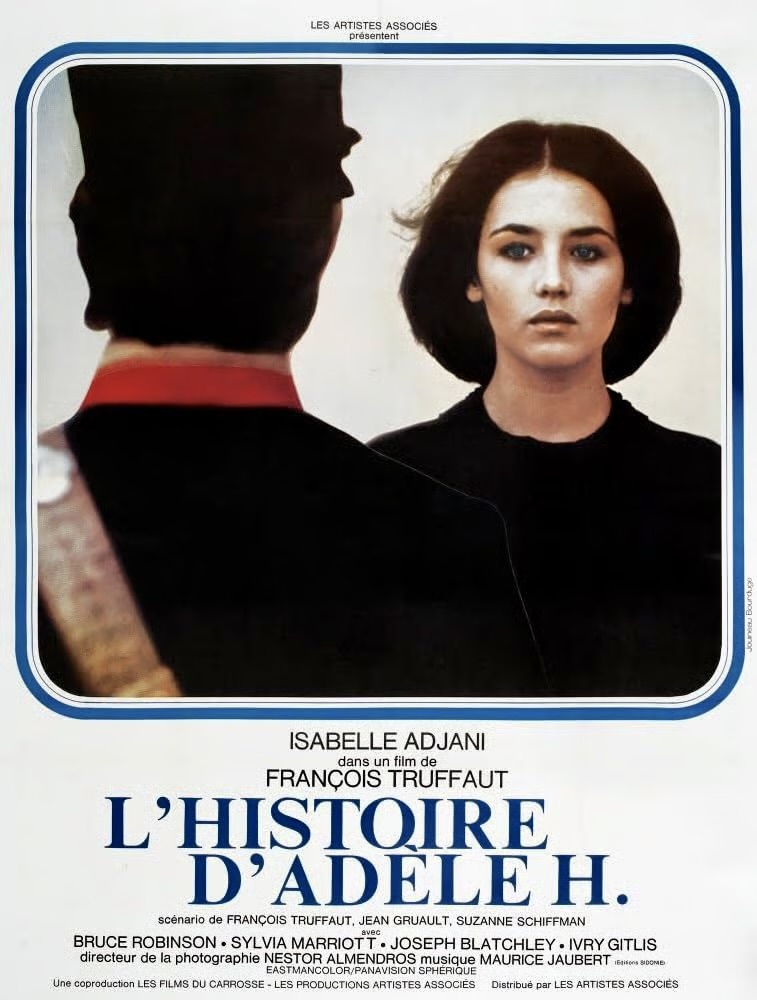

Unrequited Passion

Francois Truffaut is one of those directors whose career peaked early with the phenomenal semi-autobiographical debut film The 400 Blows in 1959 at the dawn of the Nouvelle Vague and followed it with two more masterworks – Shoot the Piano Player (1960) and Jules and Jim (1962). The next ten years were more erratic with some successes like Stolen Kisses [1968] and The Wild Child [1970] and several disappointments, which were either box office flops (Fahrenheit 451 [1966]) or poorly received by French critics such as The Bride Wore Black [1968]. Then he revived his career and critical standing with two masterpieces in a row, Day for Night (1973) and The Story of Adele H. (1975). The former was a delightful, audience-pleasing homage to moviemaking which was nominated for four Oscars (and won for Best Foreign Language Film) but the latter was a much darker affair, based on real events, and focused on an obscure literary figure, Adele Hugo, the fifth and youngest child of Victor Hugo, who was one of France’s most famous writers and poets.

Continue readingBottom Feeders

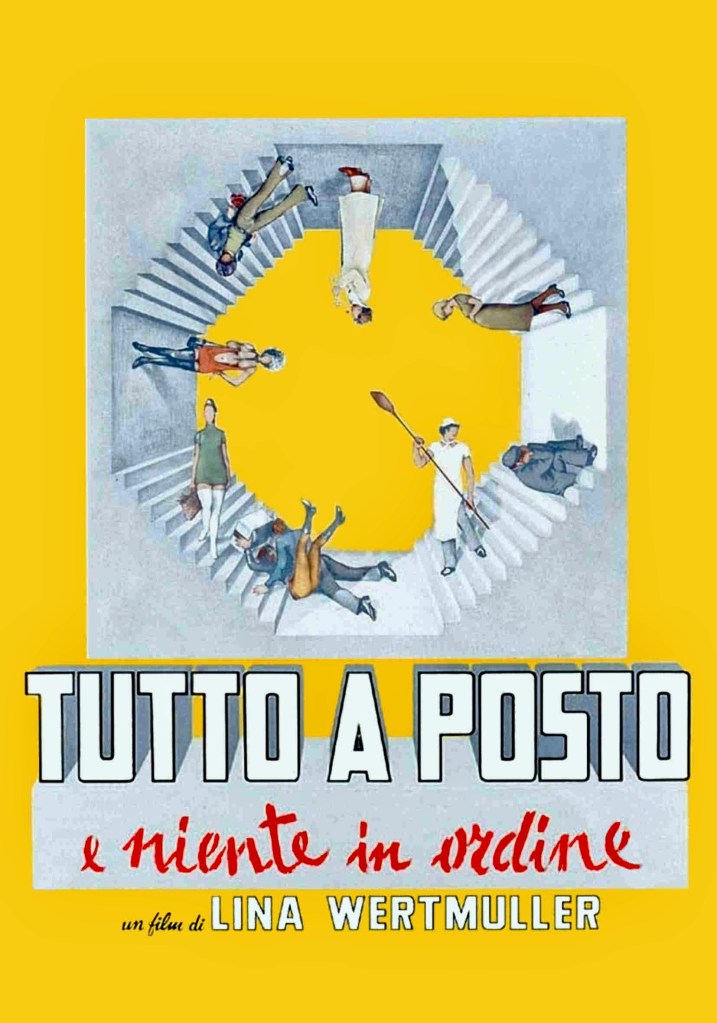

Gigi and Carletto are two naïve country bumpkins who, like many others from rural Italy and southern regions like Sicily, have come to the northern city of Milan to seek their fortunes. They soon fall in with other recent arrivals to the city seeking work and eventually set up a communal living situation in an abandoned apartment with others. Both men have big dreams and expectations but the reality is quite different from what they imagined and they fall prey to the city’s corrupting influences. It is a familiar scenario that you have probably seen in numerous other movies but director Lina Wertmuller gives it her own unique spin in Tutto a posto e niente in ordine (English title: All Screwed Up, 1974), an exuberant, gleefully crude satire that uses broad comedy and eccentric characters to magnify the myriad problems of Italy during the early 70s. This is her idiosyncratic contribution to Commedia all’italiana, a genre of comedic social commentary first created by Mario Monicelli and Pietro Germi in the late fifties/early sixties with such films as Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958) and Divorce Italian Style (1961), satires where serious themes like poverty, unemployment, marital woes and economic hardships are treated in a lighthearted style.

Continue readingMinions of the Fuhrer

You’d expect a film with a title like Hitler’s Children (1943) to be an exploitation picture, not a prestige production and you wouldn’t be wrong in most respects. But this sensationalistic melodrama about a Nazi youth and his American girlfriend struck a resonant chord with audiences of its era, making it the highest grossing film of all time for RKO Studios, surpassing even the box office receipts of King Kong (1933) and Top Hat (1935).

Continue readingWorst Family Vacation Ever?

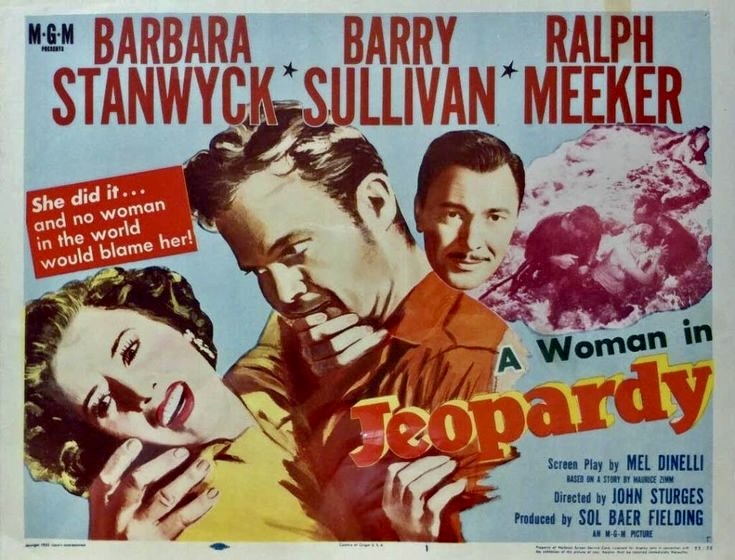

Everyone has their favorite family vacation horror story but this one takes the prize. In Jeopardy (1953), Barry Sullivan and Barbara Stanwyck play a married couple traveling with their small son (Lee Aaker) along the Mexican coast. After scouting for an ideal location for their fishing trip, they set up camp near a deserted village. The little boy wastes no time exploring his surroundings and promptly gets stranded on a derelict pier. When his father attempts a rescue, he falls beneath the rotting timbers and is pinned in the sand. High tide is just a few hours away and so is certain death unless Stanwyck can find a rescue party for her husband. She races off in the family car to seek help and is apprehended by Ralph Meeker, an escaped convict who commandeers her vehicle with no interest in saving Stanwyck’s husband.

Continue readingThe Poet of Chaos

People tend to forgive artistic geniuses for their human imperfections when their talent is so monumental – this could also apply to any super-celebrity with landmark achievements in any field from sports to politics to music – but at a certain point, there is a limit to what society will tolerate. The protagonist of Baal, a 1970 film adaptation of the Bertolt Brecht play, is the embodiment of this. A former office clerk turned itinerant poet and musician, Baal’s work propels him to the level of a literary icon, beloved by the intelligentsia and the common man. He could care less because he hates everything, including the society that helped shape his talent. More importantly, he hates himself and that self-destructive urge informs his every act, making him one of the most nihilistic and anti-social characters even conceived for the stage or screen.

Continue reading