New York City has served as the background and, in some cases, the main star in dozens of films from King Kong (1933) to The Naked City (1948) to Manhattan (1979), and usually it is depicted as a vibrant melting pot of humanity where opportunity and chance encounters can change the course of one’s life. It can also be a place of desperation, danger and soul-crushing despair and The Rat Race (1960), based on Garson Kanin’s play and adapted by him for the screen, falls into this category. Along with such films as Midnight Cowboy (1969), Death Wish (1974) and Taxi Driver (1976), this tale of two innocents being beaten down by the realities of big city life comes across like a hate letter to the Big Apple, whether that was Kanin’s intentions or not.

Continue readingTag Archives: Robert Burks

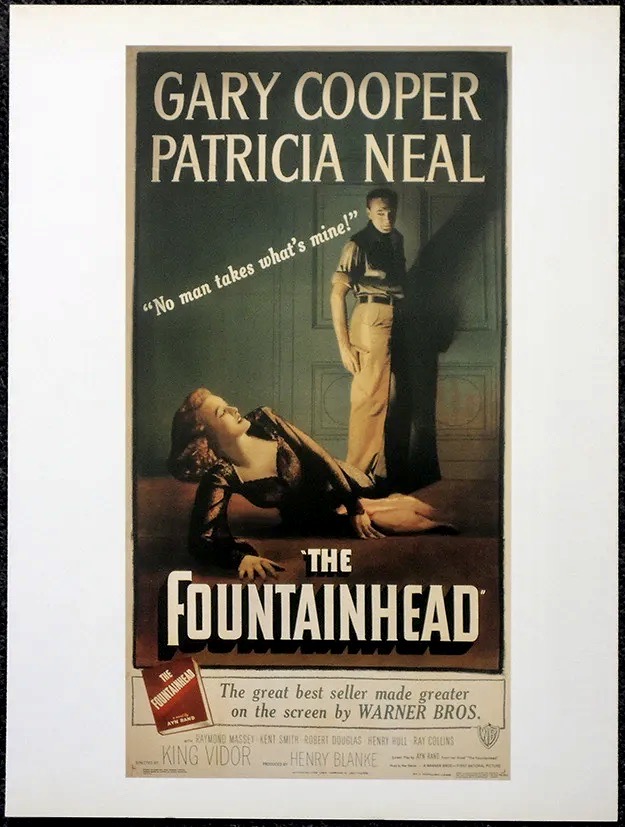

A Monument to Objectivism

If you look up the word melodrama in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the description reads “a work (such as a movie or play) characterized by extravagant theatricality.” The Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries offers a similar definition: “a story, play, or novel that is full of exciting events and in which the characters and emotions seem too exaggerated to be real.” Some popular examples of this in the movies would have to include The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), The Barefoot Contessa (1954) and The Best of Everything (1959). But they are some films in this category that are so excessive in tone and style that they belong in their own category of extreme melodrama. Among the more glaring examples of this are Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind (1956), The Caretakers (1963), which is set in a psychiatric hospital where Joan Crawford teaches karate, the Tinseltown expose The Oscar (1966), and four films – yes, four! – from director King Vidor: Duel in the Sun (1946), Beyond the Forest (1949) with Bette Davis, Ruby Gentry (1952) starring Jennifer Jones, and my personal favorite, The Fountainhead (1949), which scales dazzling heights in operatic excess.

Continue reading