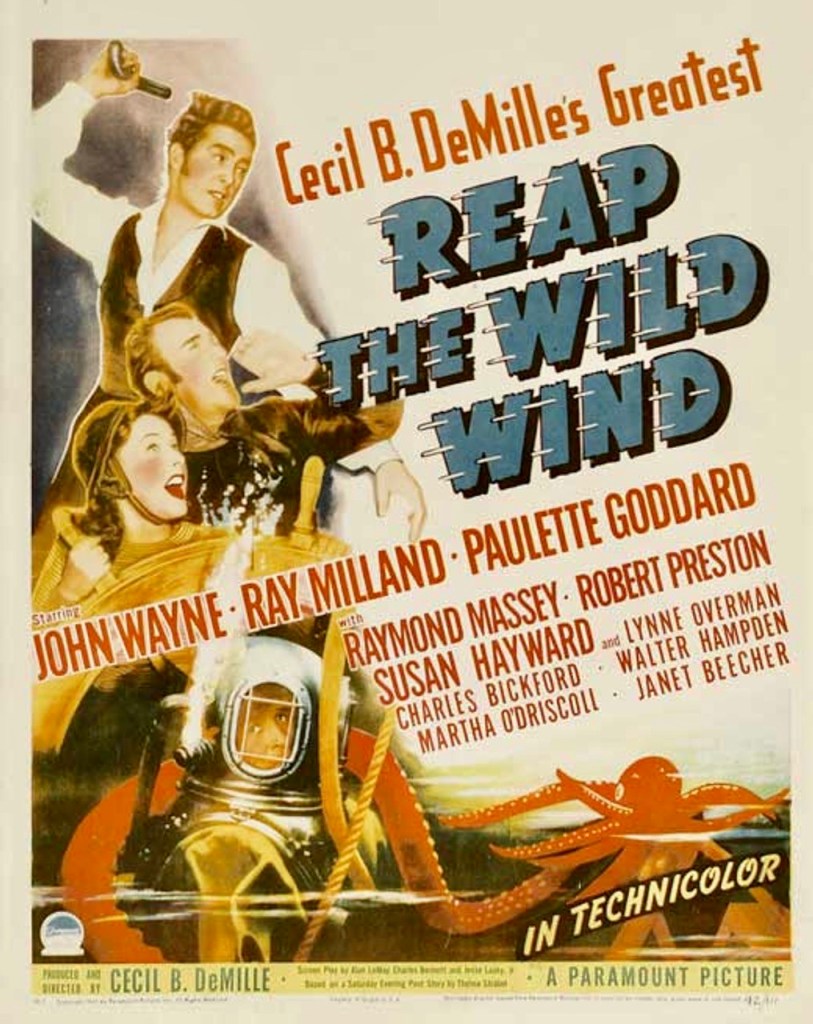

When fans of classic films from Hollywood’s golden era exclaim “They don’t make ‘em like they used to,” they are usually referring to the kind of lavish, big-budget, audience-pleasing entertainments that were the specialty of Cecil B. DeMille during the silent and sound eras. Often derided by some critics as being corny and bombastic with an exploitable mix of sex, violence and quasi-religious elements, his most popular films were always in sync with what audiences wanted from a movie during his 45-year reign as a major Hollywood director/producer. Three of DeMille’s biblical epics, The Ten Commandments (1923), The King of Kings (1927), and Samson and Delilah (1949), along with Reap the Wild Wind (1942) are still considered some of the biggest box office hits in the history of Hollywood. The latter film, in particular, is an excellent example of his larger-than-life approach to storytelling mixing rival sea captains, a hurricane, and a giant red squid into a torrid romantic saga based on Thelma Strabel’s best selling novel.

Continue readingTag Archives: Monte Blue

Eskimo (1933) – Inuit Culture on Film

How many famous or highly regarded films about the Inuit culture can you name? Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922) is probably at the top of the list but what else? The 1955 Oscar-nominated documentary Where Mountains Float, Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents (1960), Zacharias Kunuk’s 2001 epic, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001), and Mike Magidson’s Inuk (2010) are all impressive achievements which need to be better known. But one of the most moving and evocative films is from 1933 entitled Eskimo, a word which is now an outdated and offensive reference to the Inuit and Yupik tribes who populate the Arctic Circle and northern bordering regions. Continue reading

The Original Odd Couple

Either by accident or design, MGM came up with the most unlikely partnership in the history of motion pictures in the late twenties. Imagine if you can a collaboration between Robert Flaherty, the filmmaker who is generally credited with pioneering the documentary form (though some film scholars take issue with that classification), and W. S. Van Dyke II, who was known in the industry as “One Take Woody” because of his quick, cost-saving shooting schedule. Flaherty’s filmmaking method was just the opposite. His painstaking preparation for each film was legendary; both Nanook of the North (1922) and Moana (1926) took over two years to complete. Somehow these two men were brought together by MGM mogul Irving J. Thalberg for White Shadows in the South Seas (1928). Continue reading