In 1940 after France had fallen to the German army, journalist Jean Bruller and his wife, who lived outside Paris, were forced to share their home with a Nazi officer for an extended period of time. That experience inspired Bruller to write the novella Le Silence de la Mer (The Silence of the Sea) under the pseudonym Vercors. The book was secretly published in late 1941 and became known as “the first underground book of the occupation.” It also became an inspiration to the French Resistance in its depiction of using silence as a weapon against the enemy when no other option was possible. It might seem like an unusual choice for French director Jean-Pierre Melville’s feature film debut when you consider that he is mostly famous for his crime and gangster thrillers like Bob le Flambeur (1956), Le Deuxieme Souffle (aka Second Wind, 1966) and Le Samourai (1967). Then again, many consider Melville’s 1969 WW2 drama L’armee des Ombres (aka Army of Shadows) about French underground fighters in Nazi-occupied Paris his masterpiece. Add to this the fact that Melville was also an active member of the French Resistance and The Silence of the Sea makes perfect sense as his feature debut.

Continue readingTag Archives: Jean-Pierre Melville

Don’t Act Cool, Just Be Cool

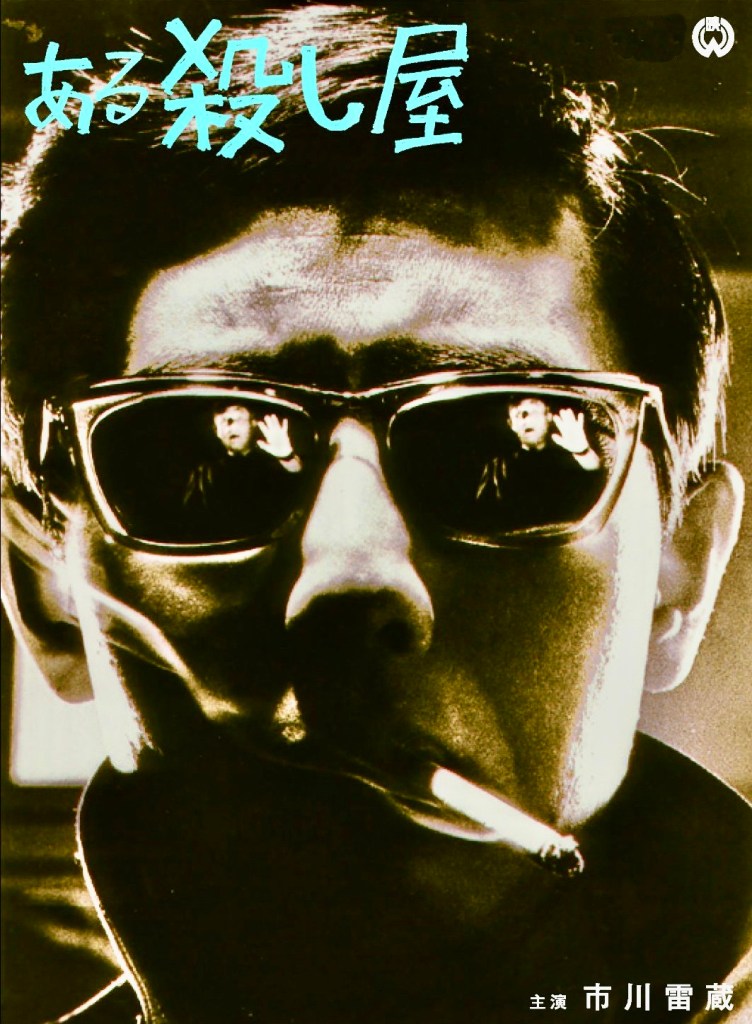

The yakuza thriller has been a prominent genre in Japanese cinema since the silent era when soon to be celebrated directors like Yasujiro Ozu dabbled in gangster melodramas like Walk Cheerfully (1930) and Dragnet Girl (1933). Once conceived as B-movies with low-budgets and rushed production schedules, the yakuza film graduated to A-picture productions in the 1970s but the genre really hit its stride in the 1960s with such stellar examples as Masahiro Shinoda’s Pale Flower (1964), Seijun Suzuki’s Tokyo Drifter (1966) and his more wildly stylized follow-up, Branded to Kill (1967). Still, there are so many superb yakuza films from this period waiting to be discovered by American audiences and one of my favorites is A Certain Killer (1967, Japanese title: Aru Koroshi Ya) from director Kazuo Mori.

Continue readingMoving Target

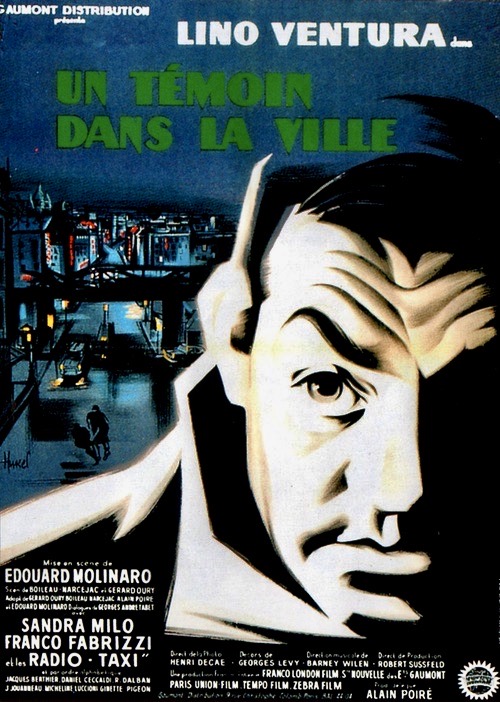

French director/screenwriter Edouard Molinaro may not be a household name in America but practically everyone knows his international breakout hit, La Cage aux Folles, from 1978. It spawned an equally successful sequel, La Cage aux Folles II (1980), but also became the basis for the smash Broadway musical La Cage aux Folles in 1984 and eventually was remade by director Mike Nichols as The Birdcage in 1996 with Robin Williams, Nathan Lane, Gene Hackman and Dianne Wiest. La Cage aux Folles was no fluke success and Molinaro was already renowned in France for his film comedies such as Male Hunt (1964) with Jean-Paul Belmondo, Oscar (1967) featuring Louis de Funes and the black farce A Pain in the…(1973), which was remade by Billy Wilder as Buddy Buddy (1981). None of this would lead you to believe that Molinaro launched his feature film career with several film noir-influenced thrillers and Un temoin dans la ville (English title: Witness in the City, 1959) is a near masterpiece, deserving to stand alongside Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows (1958), Claude Sautet’s Classe Tous Risques (1960) and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Doulos (1962). Continue reading

French director/screenwriter Edouard Molinaro may not be a household name in America but practically everyone knows his international breakout hit, La Cage aux Folles, from 1978. It spawned an equally successful sequel, La Cage aux Folles II (1980), but also became the basis for the smash Broadway musical La Cage aux Folles in 1984 and eventually was remade by director Mike Nichols as The Birdcage in 1996 with Robin Williams, Nathan Lane, Gene Hackman and Dianne Wiest. La Cage aux Folles was no fluke success and Molinaro was already renowned in France for his film comedies such as Male Hunt (1964) with Jean-Paul Belmondo, Oscar (1967) featuring Louis de Funes and the black farce A Pain in the…(1973), which was remade by Billy Wilder as Buddy Buddy (1981). None of this would lead you to believe that Molinaro launched his feature film career with several film noir-influenced thrillers and Un temoin dans la ville (English title: Witness in the City, 1959) is a near masterpiece, deserving to stand alongside Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows (1958), Claude Sautet’s Classe Tous Risques (1960) and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Doulos (1962). Continue reading

The Film Noir That Got Away

Ealing Studios. The name conjures up memories of the great British comedies such as The Man in the White Suit, The Ladykillers, The Lavender Hill Mob and Kind Hearts and Coronets. Film noir, however, is not the genre that usually comes to mind although Ealing rubbed shoulders with it occasionally in It Always Rains on Sunday (1947) and Pool of London (1951). Oddly enough, one of the studio’s final releases, Nowhere to Go (1958) was pure, unadulterated noir and a stylish, terse little thriller to boot. Sadly, it has been overlooked and unappreciated for years even though it marks the feature film debut of director Seth Holt and gave actress Maggie Smith her first major screen role. Continue reading