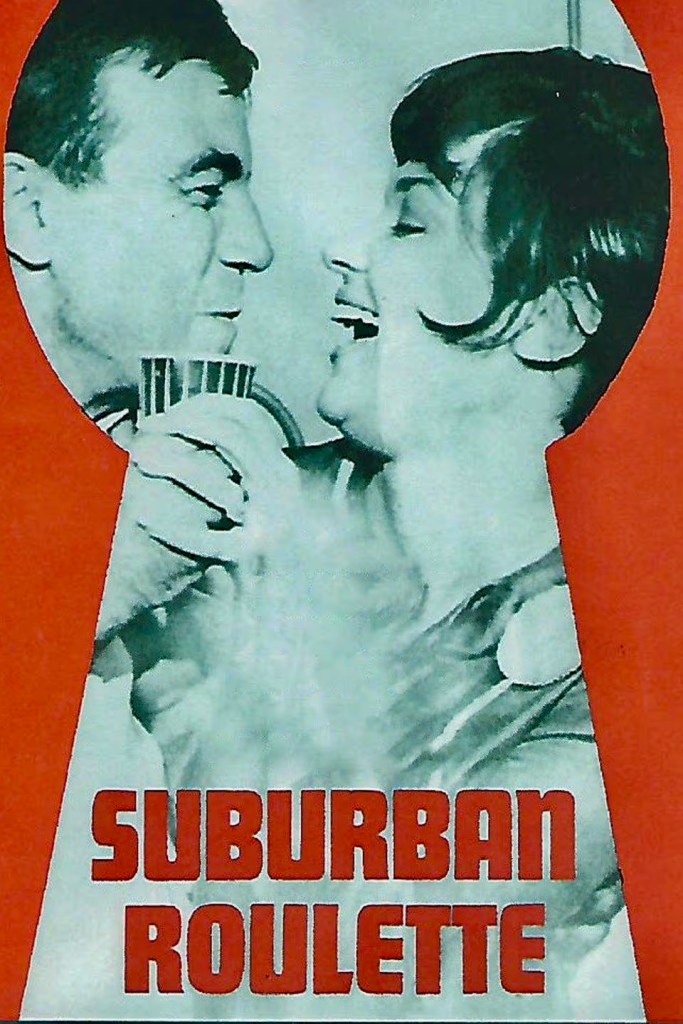

When did mate swapping parties and swinging singles soirees in suburbia in America become a social phenomenon? Some say it began during the Korean War (1950-1953) among married couples on army bases and then spread to the suburbs. One thing is certain: stories about such behavior began to appear in paperback novels, tabloid exposes and the media in the fifties and were common knowledge for most people by the time John Updike’s 1968 novel Couples was published (it focused on the lives of ten sexually active couples in a small town in Massachusetts). But even before Updike’s critically acclaimed work, sexploitation films in the sixties had been mining this subject matter in adult fare like Wife Swappers (1965), Unholy Matrimony (1967), Andy Millgan’s Depraved! (1967) and Suburban Roulette (1967), directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis.

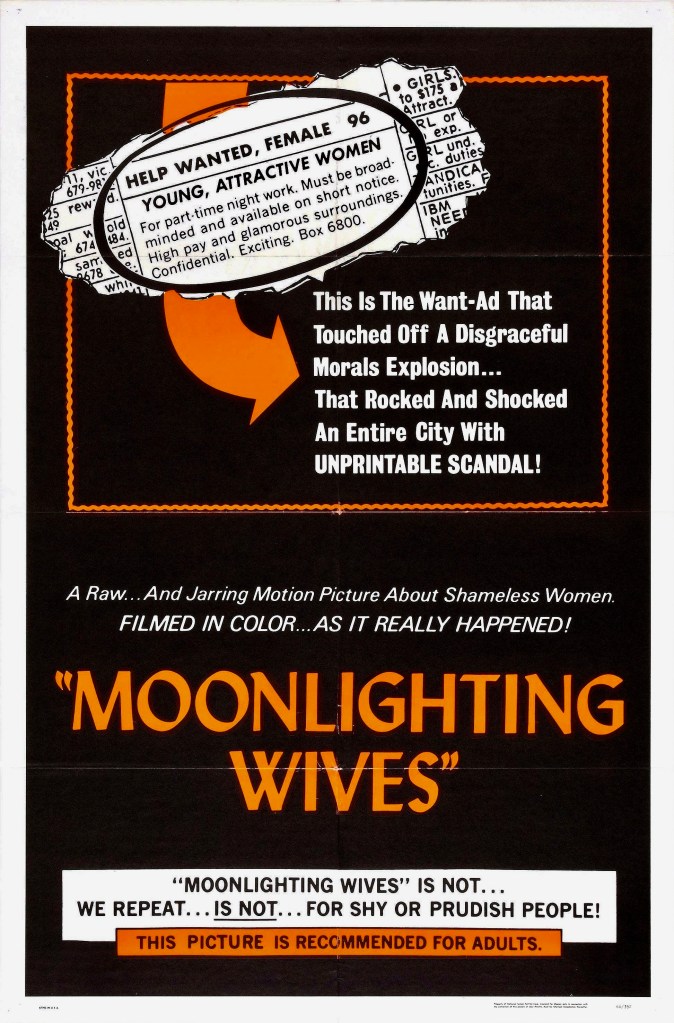

The often overlooked master of the form, however, was Joseph W. Sarno, who made his directorial debut with Nude in Charcoal (1961) and scored a drive-in hit with Sin in the Suburbs (1964), which delved into the secret sex orgies of masked participants in suburbia. Even more groundbreaking was Moonlighting Wives (1966), his first feature in color, which expanded on the swinging singles scene by combining it with a tale about a prostitution ring masterminded by a housewife in a middle class community.

Continue reading