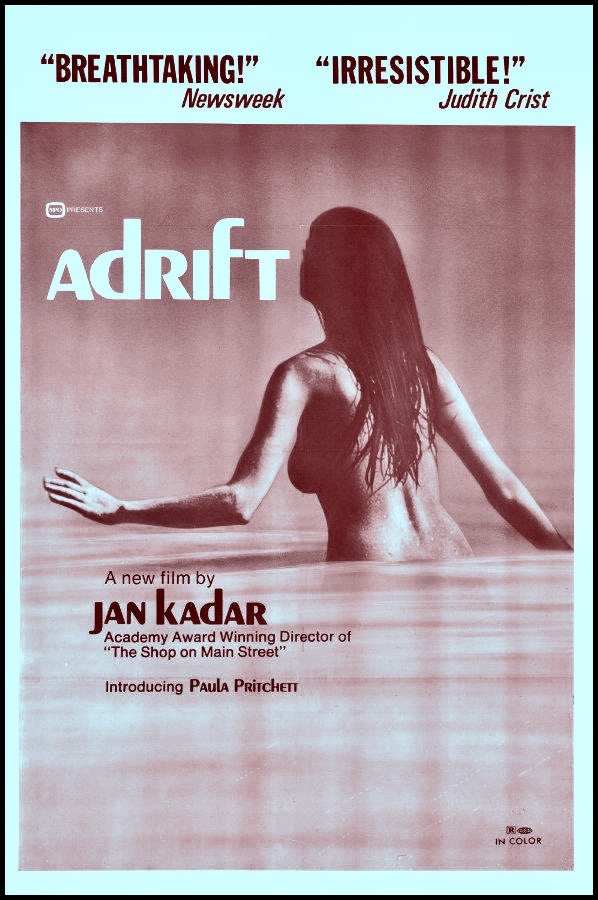

One of the most important Czech films to emerge during the Czech New Wave of the 1960s was The Shop on Main Street (Czech title: Obchod na Korze, 1965), which was awarded the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film of 1966 and snagged a Best Actress nomination for Ida Kaminska the following year. The important thing to note is that The Shop on Main Street was not really a part of the Czech New Wave. The film’s directors, Jan Kadar and Elmar Klos, were more than a generation older than the young upstarts of that movement that included Milos Forman (Loves of a Blonde), Ivan Passer (Intimate Lighting) and Jan Nemec (Diamonds of the Night), among others. And even though The Shop on Main Street made Kadar and Klos internationally famous, their other films are not as well known to most American filmgoers. That is a shame because their final collaboration, Adrift (1971), is one of their most fascinating features but the troubled production behind it is possibly one of the reasons it is almost unknown today.

Continue readingTag Archives: Czech New Wave

The Backward Life of Bedrich Frydrych

The cinematic concept of telling a story in reverse order might seem like a creative rejection of the traditional chronological narrative but it is nothing new. Polish filmmaker Jean Epstein experimented with this approach as early as 1927 with the avant-garde short The Three-Sided Mirror (La Glace a trois faces) but in recent years we have seen numerous examples of the reverse narrative in Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter (1997), Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) and two films by Christopher Nolan, Memento (2000) and Tenet (2020). Betrayal (1983), the brilliant screen adaptation of Harold Pinter’s 1978 play, is probably my favorite example of the backward narrative in terms of its cumulative emotional power but Happy End (1967) by Czech filmmaker Oldrich Lipsky might be the funniest and most visually inventive example of this novel gimmick.

Continue readingKarl Loves His Work

Popular Czech actor Rudolf Hruskinsky is the demonic central character in Juraj Herz’s The Cremator (1969).

One of my favorite movements of the 20th century in cinema was the emergence of the Czech New Wave. Out of this creative period, which lasted from roughly 1962 through 1970, the film world was introduced to such innovative filmmakers as Milos Forman (Loves of a Blonde, 1964), Ivan Passer (Intimate Lighting, 1965), Jiri Menzel (Closely Watched Trains, 1966), Vera Chytilova (Daisies, 1966) and Jan Nemec (A Report on the Party and the Guests, 1966). In recent years, other Czech directors have been reappraised and elevated in stature thanks to the proliferation of DVD and Blu-ray restorations of such movies as The Sun in a Net (1961) by Stefan Uher, Pavel Juracek’s Case for a Rookie Hangman (1970) and Valerie and Her Week of Wonders from Jaromil Jires (1970). We can now add to that list The Cremator (1969), Juraj Herz’s macabre fable, which is finally being recognized as one of the key films from the Czech New Wave. Continue reading

Ivan Passer’s Intimate Lighting

Krzysztof Kieslowski placed it on his Top Ten list for a Sight & Sound magazine poll. Dave Kehr, formerly of The Chicago Reader, called it “one of the finest works of the short-lived Czech New Wave.” The New York Times noted that Intimate Lighting (1965) was one of those movies that “loses none of its charm, to age or to repeated viewing,” and countless other critics who have seen it have championed this small-scale but beautifully observed character study about the brief reunion of two musician friends and their realization of how their lives have substantially changed since their school days. Continue reading

Krzysztof Kieslowski placed it on his Top Ten list for a Sight & Sound magazine poll. Dave Kehr, formerly of The Chicago Reader, called it “one of the finest works of the short-lived Czech New Wave.” The New York Times noted that Intimate Lighting (1965) was one of those movies that “loses none of its charm, to age or to repeated viewing,” and countless other critics who have seen it have championed this small-scale but beautifully observed character study about the brief reunion of two musician friends and their realization of how their lives have substantially changed since their school days. Continue reading