The following conversation with Peter Bogdanovich was conducted in April 2010 just prior to the first official TCM Classic Film Festival in which the director co-hosted a screening with Vanity Fair writer David Kamp of Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons. Bogdanovich, of course, was a close friend of Welles’ and is the creator of that indispensible interview collection, This is Orson Welles. Among other topics discussed are such films as Targets, What’s Up, Doc?, Paper Moon, Saint Jack, unproduced Welles’ projects like Heart of Darkness and Welles’s obsession with fake noses.

Jeff Stafford: The Vanity Fair article that David Kamp wrote on The Magnificent Ambersons made it sound like the search for the missing footage [from the film] has pretty much been exhausted and we should give up the matter. But from your own research do you consider it a lost cause at this point?

Jeff Stafford: The Vanity Fair article that David Kamp wrote on The Magnificent Ambersons made it sound like the search for the missing footage [from the film] has pretty much been exhausted and we should give up the matter. But from your own research do you consider it a lost cause at this point?

Peter Bogdanovich: Well, I hate to say that because I still have some kind of small shard of hope that someday I’ll get a phone call that says they found it in the depths of Rio or something.

JS: Which seems like the most logical place for it. If it does exist, it would probably be there.

PB: Yes, I know Orson tried to find it for years.

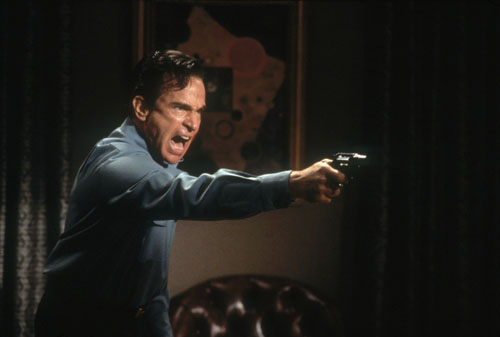

An example of the superb cinematography and set design from Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

JS: One of the stories that came out in the article – and maybe it’s a folk tale – but it was said the studios used to discard film footage and dump it in the ocean off of Santa Monica. And I’d heard that might have been the fate of the Ambersons footage. Was that a standard practice for studios then?

PB: Yeah, to make room for more footage.

JS: I just assumed they would burn it or something instead.  PB: They used to burn it when there was silver in it…silver nitrate. Actually Ambersons would have had silver nitrate so maybe they burned it but I had heard that Desilu Studios had dumped it sometime in the fifties. I did a lot of research myself for my book that I did on Orson and there’s an awful lot about Ambersons in there.

PB: They used to burn it when there was silver in it…silver nitrate. Actually Ambersons would have had silver nitrate so maybe they burned it but I had heard that Desilu Studios had dumped it sometime in the fifties. I did a lot of research myself for my book that I did on Orson and there’s an awful lot about Ambersons in there.

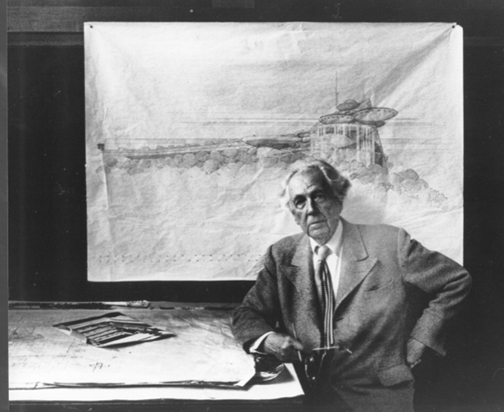

JS: Yes, there was something in your book This is Orson Welles that I wanted to ask you about. At one point you talk about Anne Baxter’s grandfather, Frank Lloyd Wright, who would come to the set occasionally and observe. I wondered if you had any further details about that or any conversations he had with Orson?

PB: Well, according to Orson, Frank Lloyd Wright was horrified by the sets and said they should all be burned and Orson tried to explain that he wasn’t trying to glorify the era but that this was the authentic facsimile of how the houses were and Frank Lloyd Wright couldn’t be mollified. He thought they were so horrible.

JS: I had heard originally that Orson wanted Mary Pickford for the Dolores Costello role. What do you think it would have been like if she had been cast? Would she have been good in that part?

PB: Yeah, it would have been great.

JS: I thought Dolores Costello was fine in the role….

PB: She was fine but Mary Pickford would have added an additional resonance because…people forget what a big star she was. She dwarves anybody today.

JS: This was toward the end of Pickford’s career so I don’t know if she still had a large fan base. Do you think if Pickford had been cast, the film would have been more popular?

PB: Well, it would have raised the curiosity level because Dolores Costello was never a big star.

JS: Today, looking at The Magnificent Ambersons, what are your impressions? What do you think are the strengths of it based on the existing cut?

PB: The first hour is – with the exception of a few annoying, little cuts here and there and some sequences that could be missed – is pretty much the way as Orson said. It’s quite close to what he had in mind. It’s this last half hour that’s a mess.

JS: Some questions about Orson Welles’ early career. I had talked to Norman Lloyd recently and he told me that originally Orson was going to do Heart of Darkness before he did Citizen Kane and I was curious if you had ever seen the script for that?

PB: Yes.

JS: Was the Heart of Darkness script going to be a departure from the Joseph Conrad novel in terms of the setting and period or was Welles going to do a faithful adaptation?

PB: It was pretty faithful. The biggest trick was that he was not going to appear himself; it was going to be completely from his point of view. And the only time you see him is if there is a reflection or a mirror or something which Robert Montgomery tried with Lady in the Lake and I think rather unsuccessfully.

JS: So that whole idea must have scared RKO.

PB: I don’t think they liked that idea on top of the fact that it was quite expensive. But there were a number of scripts that Orson almost did instead of Citizen Kane.

JS: What were some of those?

PB One was called The Smiler with the Knife. Another was called The Way to Santiago…they were both based on novels. He wanted Lucille Ball for The Smiler with the Knife and she wasn’t a big enough name. She ended up owning the studio.

JS: Sweet revenge. What are your feelings about Orson Welles as a film actor? He made so many films for the money but I was curious what films you admired him in when he was working for other directors.

PB: Well, I think first and foremost The Third Man. It was his best performance for other directors. It remains an iconic performance and one of his best. It’s the only one he ever did without any makeup. Yeah, no fake nose.

JS: What was the deal with the fake noses?

PB: He didn’t like his nose.

JS: It probably looked better than the fake nose though.

PB: Well, you tell that to an actor. If they have a thing about their nose, it’s hard to make them understand.

JS: One thing I love about This is Orson Welles is that you asked him about almost every single movie he ever made and he actually commented on just about all of them. But he did make one statement which I thought was curious. You were discussing The V.I.P.s with him and he said, “My claim that I’ve never seen a film I’ve been in breaks down there because I saw The V.I.P.s – couldn’t help myself. They ran it in a plane.” I thought it interesting that he stated that he wouldn’t see himself on screen. Do you think that he was exaggerating or that that statement was true?

PB: No, he couldn’t stand it.

JS: Even in his own films?

PB He had trouble with it. I know he didn’t like himself much. He was very self-critical.  JS: I had read where Welles had tried to buy the rights to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 after it was published and was unsuccessful. But then, ironically, he ends up being cast in one of the roles. And you interviewed him on the set of that film, correct?

JS: I had read where Welles had tried to buy the rights to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 after it was published and was unsuccessful. But then, ironically, he ends up being cast in one of the roles. And you interviewed him on the set of that film, correct?

PB Yes, in Guaymas, Mexico.

JS: What was that experience like for him?

PB: He was feeling miserable throughout. He didn’t like it. Everybody was quite deferential. And Mike [Nichols] organized an Orson Welles film festival for his arrival and Orson was horrified at things like that. It was not the way to his heart so it put him off. Also, he and Mike didn’t agree on how to interpret the character. Orson wanted to play him as so jaded that he was weak with exhaustion…from the nightmare he had been going through…where Mike wanted it more gruff and bullying and more in the McHale’s Navy-Sergeant Bilko kind of thing. Which Orson just hated. He played along with it but he didn’t like it.

JS: I haven’t seen it in years and barely remember him in it. Did you like it?

PB: It wasn’t what he wanted at all. It was pretty conventional. I saw him play it his way a couple of times and it was quite funny.

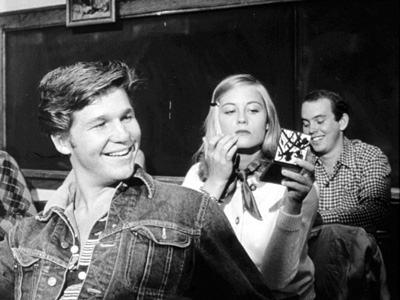

Chimes at Midnight (1965 France/Spain/Switzerland)

Directed by Orson Welles

Shown from left: Jeanne Moreau, Orson Welles

JS: Of Welles’ later period from say, 1950 on what do you think is his best film?

PB: Well I think Othello and Chimes at Midnight are great and Touch of Evil is a masterpiece. I think those are the three best films of that period.

JS: On the Criterion Collection release of F for Fake is a documentary about Orson Welles that includes footage from his One Man Band project where is playing different characters and different instruments. What was that? It looked fascinating.

PB: That was basically all there was of it. It was sort of him alone, a one man show. I think it was supposed to be a television special. There was a documentary made called The One Man Band, made in Germany and Showtime bought it and ran it on their cable network and asked me to do an English version of it. And it required quite a bit of editing – I recut it and recorded a narration that I did.

JS: I’d like to ask you about some of your own films now. It must be very gratifying to see Jeff Bridges win the Best Actor Oscar after directing him in his first Oscar nominated performance in The Last Picture Show.

PB: Yeah, it was really nice. I was really proud of him. Very happy that he’s finally won. He’s deserved it every time. He’s a brilliant actor and I loved working with him. I’m glad he finally got recognition from his peers. It’s about time. He was really great in Crazy Heart. It’s an extraordinary performance.

JS: The other thing I think is interesting about The Last Picture Show is that it was Larry McMurtry’s first screenplay and I know that, generally speaking, they keep the world of screenwriters and novelists separate in Hollywood but you decided to use him as a screenwriter for the film. Was that a difficult thing to convince the studios to do?  PB: No, because I said I would do it with him and since he’d written the book and the dialogue in the book was virtually all of the dialogue we used, I thought that was enough to give him credit. He didn’t really write the screenplay. He would write a location and then what happens without any thoughts. We did it together. He would write a few pages and do the dialogue…mainly the dialogue…and then send it to me. Then I would sort of make it into a screenplay.

PB: No, because I said I would do it with him and since he’d written the book and the dialogue in the book was virtually all of the dialogue we used, I thought that was enough to give him credit. He didn’t really write the screenplay. He would write a location and then what happens without any thoughts. We did it together. He would write a few pages and do the dialogue…mainly the dialogue…and then send it to me. Then I would sort of make it into a screenplay.

JS: Do you think he enjoyed that process?

PB: He didn’t particularly.

JS: It doesn’t look like he got involved in much screenplay writing after that if you look at his filmography.

PB: Not for some time. He sort of got into later.

JS: This brings me to another screenplay adaptation that you did with writer Paul Theroux for one of my favorite movies, Saint Jack. That was another first screen credit for him as well. Was that a similar situation?

PB: You know when somebody writes a book and you base the movie on the book…I don’t know, I feel if you don’t end up using their screenplay then you should give them some credit and the truth of the matter is…Paul did write a screenplay but we didn’t use any of it. I gave him credit anyway. He wouldn’t have gotten it if it went into arbitration. But I just feel that it’s his book and we used a lot of his book and he did try to write a screenplay but it wasn’t really usable.

The screenplay on that movie was really written largely on location while we were shooting. The construction for the screenplay was one of the big things we did get from the writer, Howard Sackler. In the book the Denholm Elliott character [William Leigh] only comes to Singapore once and everything that happens in the movie happens in the first visit that he makes to Singapore…everything, everything at this one time and then he dies. So Sackler, who was a good playwright – He wrote The Great White Hope and wrote a good deal of Jaws but didn’t take credit – came up with the idea that Denholm’s character should come to Singapore three times and that would give us our three act structure. And that’s what we did. And that was the construction we used but the actual scenes, the dialogue and all that were actually written while we were there.

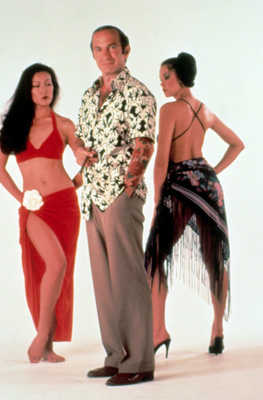

Peter Bogdanovich (far left) and Ben Gazzara (far right) appear in the film Saint Jack (1979), directed by Peter Bogdanovich.

JS: Was that stressful to be writing it while you were on location?

PB: It became easier because we were there and in the book there was very little stuff with women. It’s a story about a pimp and hookers and there was hardly any stuff with the hookers so we did some research – Gazzara and I – and found out a lot of interesting things. In fact, some of the working girls were actually in the picture. They were wonderful.

JS: You pulled together such a great group of people for that movie – Denholm Elliott, James Villiers, Joss Ackland and, of course, Ben Gazzara, who’s just fantastic in it and even George Lazenby and yourself.

Ben Gazzara and Denholm Elliott (right) star in the 1979 film, Saint Jack, directed by Peter Bogdanovich.

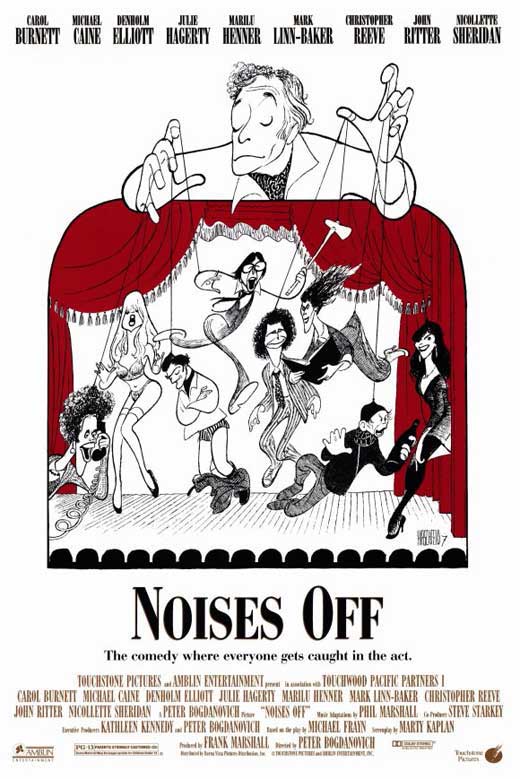

PB: Well, we got very lucky because originally I wanted Charles Grodin to play the part I played and he didn’t want to come all the way over to Singapore. So then he said, “Why don’t you play it?” and I said OK. That was a good idea. It might be fun. And Ben sort of directed me in my scenes and we needed someone to play the senator and we didn’t have a lot of money. Turned out George Lazenby was doing an episode of Hawaii Five-0 so he was halfway there because he was in Hawaii so we said, “Ok, have George come over,” and that was that. The other English actors we cast in London; it was a good cast. I’ve always been a great admirer of Denholm Elliott ever since Nothing But the Best. He’s a great, great actor. We used him again in Noises Off [1992], it was his last film.  JS: I was expecting Saint Jack to get nominated for Oscars when it came out because I thought the performances were so strong and was surprised when it was ignored. But weren’t the reviews positive from the critics in general?

JS: I was expecting Saint Jack to get nominated for Oscars when it came out because I thought the performances were so strong and was surprised when it was ignored. But weren’t the reviews positive from the critics in general?

PB: Yes, very positive except for The New York Times. [Vincent] Canby slept through it and when he woke up he said, “Oh, it’s a kind of Alan Ladd picture.” I mean he had no idea what it was. I was there while he slept through it. But the reviews were generally good but it wasn’t a big moneymaker. And it was also before this kind of independent movie culture was happening so it was a little bit ahead of its time. I think if Saint Jack had come out now, a few years ago or in this climate it would do much better.  JS: A few questions about What’s Up, Doc? After The Last Picture Show, you decided to do a screwball comedy, which hardly anybody in Hollywood had done for years. Was that a hard sell to the studios?

JS: A few questions about What’s Up, Doc? After The Last Picture Show, you decided to do a screwball comedy, which hardly anybody in Hollywood had done for years. Was that a hard sell to the studios?

PB: It wasn’t that I wanted to do it. It just sort of happened. What actually happened was….well, it’s a long story. I’ll try to tell it shorter but my agent had gotten Steve McQueen in to see an early cut of The Last Picture Show because he was looking for a director to do The Getaway. And Steve saw the picture and loved it and asked if I would do The Getaway and I agreed to do it. Then Streisand’s agent heard that McQueen had me for his next picture so she wanted to see the picture. So she saw an early cut. It wasn’t quite finished but it was finished enough to show. It was still a work print. So she saw it and she was doing a picture for Warners called A Glimpse of Tiger and wanted me to direct that right away and I didn’t like the script. It just didn’t interest me and they wanted Barbra to do a picture.

Barbra Streisand and Ryan O’Neal star in What’s Up, Doc? (1972), a screwball comedy by Peter Bogdanovich.

Warners had her but they couldn’t get a director for this thing so John Calley called me over to his office – he was head of Warners at the time – and he said, “Barbra really wants to do a picture with you. We both would like to do a picture with you. Why don’t you do this picture?” And I said, “I don’t like the script John. And he said, “Well, if somebody said to you, ‘Do you want to do a picture with Barbra Streisand, would you do it?’ I said, “Yeah.” Calley: “What would you do?” Bogdanovich: “I don’t know – a screwball comedy.” He said, “Whatdaya mean, what?” Bogdanovich: “Like Bringing Up Baby. You know, square professor, crazy girl, messes up his life and she marries him or something.” And he said, “Well, why don’t you do that?” And so I said alright and he said, “Who would you get to write it?” And I said “Well, [Robert] Benton and [David] Newman worked with me at Esquire,” and he said, “Good. They just did a picture for us. Call em.” I said, “Can I produce it?,” he said sure so I left the office producing and directing Barbra Streisand’s next picture with Benton and Newman writing the script. It was as arbitrary as that.

JS: I never knew it came together like that.

PB: That’s how it came together. And Bob and David said they only had three weeks because they had another assignment. I said, “Why don’t you guys come out here and we’ll hole up for three weeks. If Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht can write the scrip to Scarface in eleven days, we can get something done in three weeks.” So we did knock out a script in three weeks and it wasn’t really good enough. I did a quick pass on it that was still not good enough. But I got Ryan [O’Neal] and Barbra to sit down and read it with me and they were so busy trying to make sure that I liked them that they didn’t really notice that the script needed quite a bit of work. So they committed to it.

Then John Calley said, “Don’t you think the script needs some work,” and I said, “Yeah, definitely.” So he said, “How about Buck Henry?” and I said, “That’s a great idea,” and I met with Buck and he added some ideas and his opening line to me was, “You’re gonna hate me but I don’t think it’s complicated enough.” I said, “Do you think we need another suitcase?” and he said “Yeah,” so it went to four suitcases. So we said, what should the fourth suitcase be? – and The Pentagon Papers was all over the newspapers at the time – so we said let’s make it The Pentagon Papers. And we had somebody in the cast who looked a little like [Daniel] Ellsberg. And Buck wrote his draft based on our draft fairly quickly and we were in production before The Last Picture Show opened. We were shooting before Picture Show opened.

Kenneth Mars plays an egocentric critic modeled on John Simon in What’s Up, Doc? (1972), directed by Peter Bogdanovich.

JS: So the whole film took how long from the time you actually started filming?

PB: It was scheduled for 72 days and we did it in 71.

JS: The character that Kenneth Mars plays was said to be modeled on critic John Simon, I was curious if Simon ever reviewed the film or commented on it.

PB: He wasn’t very happy. He said to me once – very viciously – (imitates his voice) “I hope the next time you use somebody to play me you get a good actor!”

JS: I love Kenneth Mars in that.

PB: Oh, Kenny is so funny. I told him to watch John Simon on The Dick Cavett Show. That’s what he came up with.

Madeline Kahn & Austin Pendleton star in the 1972 screwball comedy, What’s Up, Doc?, directed by Peter Bogdanovich.

JS: Simon’s reviews always got so personal where he would stoop to criticizing someone’s physical flaws…

PB: Oh, he was awful that way.

JS: And I never really thought he was a gifted film critic.

PB: No, it always sounded like it was badly translated from the Croatian.

Madeline Kahn, in her first major film role, practically steals What’s Up, Doc? (1972) from her co-stars, Barbra Streisand & Ryan O’Neal.

JS: My favorite part of What’s Up, Doc? is Madeline Kahn. I think she’s one of the great unsung actresses of her era. And I was curious how you came to cast her because that was her first film role, right?

PB: We introduced her in the picture. She got an “Introducing Madeline Kahn” credit. I went to New York and I’m trying to remember the name of the casting woman – Nessa Hyams. She wanted me to meet a few people in New York and Madeleine was on Broadway with Danny Kaye in a musical called Side by Side, I think it was [It was actually Two by Two]. And I didn’t have time to see the musical and was only in New York two or three days and I met with Austin Pendleton and Madeline. And Madeline just came in and knocked me out. She didn’t read. We just had a talk. I just kept laughing and she said, “What are you laughing at?” I said, “You’re funny.” She didn’t know she was funny. She didn’t try to be funny. She just was funny. And we cast her from that conversation that we had.

I was very excited about her because she has that voice and she had this kind of funny quality. And she’s great in the picture. And I did Paper Moon with her too and then we did At Long Last Love and she was great in all three.

JS: A question about Paper Moon. I always thought it was a shame that she and Tatum O’Neal had to run against each other in the Best Supporting Actress category because I thought they both deserved to win. And I felt that Tatum really should have been in the Best Actress category because she was the main actress, even if she was a child.

PB: They [the studio] thought that she wouldn’t win Best Actress but they thought she would win Best Supporting. You know, for an eight or nine year old, you’re too young to win Best Actress so this was just too much for them. I wasn’t involved in that maneuver but I think the studio thought better to put her up for Supporting. It was surprising this year that Christopher Plummer, who plays the lead in The Last Station, was Supporting Actor.

JS: Yes, once again. Do you think that was because they thought he had a better chance at Best Supporting Actor?

PB: Yeah, I think so.  JS: I’d like to ask a few questions about your books. Who the Hell’s In It? In the Sal Mineo chapter, there’s a mention about wanting to cast him in a film about Bugsy Siegel that Howard Sackler was going to write.

JS: I’d like to ask a few questions about your books. Who the Hell’s In It? In the Sal Mineo chapter, there’s a mention about wanting to cast him in a film about Bugsy Siegel that Howard Sackler was going to write.

PB: Howard Sacker did write it. We were going to make it at Universal. And then he decided not to make it. It was a good script.

JS: So the Barry Levinson film Bugsy was not related to this project, right?

PB: Yes, it was a totally different script. The same basic idea but Howard’s script was very good.

JS: There’s another chapter on Anthony Perkins where you mention that agent Sue Mengers was the person representing you when you first started and Perkins, Anthony Newley and you were her only three clients at the time. And she was one of the few high profile female agents in Hollywood then. I was curious what enabled her to amass such a powerful client base so quickly.

PB: The success of The Last Picture Show and What’s Up, Doc?..particularly, What’s Up, Doc? Picture Show was already shot but hadn’t come out and I moved over to ICM or whatever it was called at that point. Ted Ashley was running it and [David] Begelman was representing Streisand but Sue Mengers really maneuvered the What’s Up, Doc? thing to Ryan and me and Barbra. She created that package really. And that was the second biggest grossing film of the year, you know, after The Godfather. So that was a huge thing for her and I became the hottest director in Hollywood and I signed with her so she started getting everybody in town.

The suspense thriller, The Last of Sheila (1973), features (from left to right) James Mason, Raquel Welch, Joan Hackett, Dyan Cannon and Richard Benjamin.

JS: She sounded like a real character. There’s that movie The Last of Sheila where I hear that Dyan Cannon was kind of doing an impersonation of her in the film.

PB: She was, yeah. Tony told me that. I don’t think it’s in the chapter [on Perkins] but she was doing Sue Mengers. She was a character.

Director Agnes Varda (center) stands next to Warhol star Viva on the set of the 1969 film, Lions Love.

JS: Agnes Varda. A question about her. I’ve seen Lions Love and wondered how you ended up in that.

PB I was at the bookstore when they were shooting and she said, “Would you be in it?” and I said OK.

JS: But you already knew her, right?

PB: No, I didn’t know her. I was just there. I had made one film I think and I was at Larry Edmunds bookshop quite often and she was shooting – as I remember, I’m only in it for a moment, aren’t I? I’ve never even seen it.

JS: Well, I don’t think it holds up very well but it’s totally a time capsule of Los Angeles in the late sixties.

JS: Do you still see movies in theatres or prefer to watch them at home now?

PB: Well, if I’m really interested in a movie I prefer to see it in a theatre. ![]() JS: What do you think about the current technology where you’re able to watch a clip from Lawrence of Arabia on your iPhone or some other mobile device? In some ways, it may be a way of preserving film history with younger generations into film culture but it also seems like such a desecration at the same time. I wonder what David Lean would have to say about that?

JS: What do you think about the current technology where you’re able to watch a clip from Lawrence of Arabia on your iPhone or some other mobile device? In some ways, it may be a way of preserving film history with younger generations into film culture but it also seems like such a desecration at the same time. I wonder what David Lean would have to say about that?

PB: Probably swiveling in his grave. The problem is – you’ve put your finger on what the big problem is with the younger generation. The reason they don’t appreciate older films is because they never see them the right way. So they’re used to seeing them on small screens, in black and white, which sometimes is too dark for the television, sometimes the pace is too fast because everything is harder to see on TV, even with the big screen TVs. It’s not the same as seeing it on the big screen. And the fact that you can stop the film and rewind it or put a bookmark in it as though it was a book and come back and see it again the next day…All that is awful. All that goes against the experience of actually seeing the movie. If you see a movie like Avatar in that kind of way, it wouldn’t be impressive either. The older films were always meant to be seen on the big screen. Nobody thought they’d be shown on a little screen – you know, postage sized. No, I think it’s really a tragic loss for younger people to not be exposed to films in the right way. That’s why I think it’s great that TCM is doing a festival where you’re going to see those films on the big screen.

JS: I wanted to ask you about a few earlier things you had done such as Targets because of Boris Karloff. I know you had a very rushed schedule on that and only had him for five days. But during that brief time, did you ever have an opportunity to talk to him about some of the people he worked with like James Whale or Bela Lugosi?

PB: Not really. We talked about Howard Hawks because we used a clip from The Criminal Code [in Targets that Karloff and Bogdanovich view together]….I said, “You know he really had a way with a story,” and Boris ad-libbed, “Indeed he does. He gave me my first really important part’…. And we talked about the monster. I said, “How do you feel about Frankenstein?” and he said (imitates Karloff), “The Monster?” And he felt that it had given him a niche and given him a career, really. And he was perfectly happy with it and never regretted it.  He was different than the character in the movie [Targets] who regretted a lot of crap he’d made. Boris never expressed that kind of attitude. He was a professional and he did his best with no matter what he was given to do. He was a lovely man. He worked really hard. We had very long hours. For example, we did everything with him at the drive-in [theatre] in one day and one night. I don’t know how we did all that.

He was different than the character in the movie [Targets] who regretted a lot of crap he’d made. Boris never expressed that kind of attitude. He was a professional and he did his best with no matter what he was given to do. He was a lovely man. He worked really hard. We had very long hours. For example, we did everything with him at the drive-in [theatre] in one day and one night. I don’t know how we did all that.

JS: It must have been hard on him because he was in such poor health at the time.

PB: He was. He had emphysema and he could hardly walk because he had braces on his legs. But he was a pro, right up to the finish. He was great. He liked the script of Targets a lot, he liked me and we got along well.

Mildred Natwick and Barry Brown star in Daisy Miller (1974), co-starring Cybill Shepherd in the title role.

JS: There was one actor you used in one of your films that I had seen in only a few things, mostly on television dramas, and in Bad Company opposite Jeff Bridges – Barry Brown. And he appeared in your film, Daisy Miller. He’s someone I thought was a really good actor and promising but just a few years after Daisy Miller he seemed to fall apart and then killed himself.

PB: Well, he had a drinking problem. He was very promising and I thought he was really good in Bad Company but his drinking problem came up in Daisy Miller and got me pretty upset with him. And he had an obsession with death. He would turn to the obituaries as soon as he got a newspaper. He was a strange cat. He was very unusual. He was very right for the part in a way. He was sort of winterborn. Cybill [Shepherd] and I used to kid around and say, “Well, he IS the part.” Which wasn’t really a compliment but he was a really good actor and he’s good in the picture. It’s just that he was his own worst enemy.  JS: Are there any film festivals that you attend on a regular basis?

JS: Are there any film festivals that you attend on a regular basis?

PB: I used to go to Telluride quite often because they’d invite me quite often. I’ve been invited to a lot of film festivals but I don’t go very often. And I’m not that keen on film festivals. There’s just too much movie talk. Of course I’ve been to lots of film festivals where there have been tributes to me but I don’t really like all that stuff.

JS: Are you working on anything right now for television or film that will be coming out soon?  PB: I’m hoping to shoot a picture this summer but there are three or four things swirling around and I’m not sure which one is going to be ready. I’ve got a comedy that I want to do very badly called Squirrels to Nuts…which, I hope is a comedy with that title. It’s kind of in the What’s Up, Doc?/They All Laughed family. It’s a screwball comedy, but it’s a little edgier because it’s about an escort.

PB: I’m hoping to shoot a picture this summer but there are three or four things swirling around and I’m not sure which one is going to be ready. I’ve got a comedy that I want to do very badly called Squirrels to Nuts…which, I hope is a comedy with that title. It’s kind of in the What’s Up, Doc?/They All Laughed family. It’s a screwball comedy, but it’s a little edgier because it’s about an escort.

JS: I loved They All Laughed. What a great cast. Colleen Camp and [Ben] Gazzara…it kind of reminded me of a Jacques Demy film.

PB: That’s my favorite of all my films.

JS: It’s got a very European flair to it that’s just so charming. Once again, I don’t really understand why it didn’t draw a bigger audience.

PB: That was a problem because Dorothy [Stratten] was murdered and that put a pall over the picture quite a bit. And I didn’t react well so I ended up trying to distribute the film myself which was probably one of the biggest mistakes of my life because I blew five million bucks and didn’t end up with the picture. You just can’t self-distribute. It doesn’t work, you just can’t do it. We opened in Westwood [in Los Angeles] and played fifteen weeks at Beverly Hills in The Music Hall..sold out performances, people loved it. And we went to the Mann Theatres to do the break and we outgrossed everybody in Westwood the first week of the release.

But they still pulled us out because Paramount wanted the theatre for Reds. So you just can’t do it. We got screwed left, right and sideways. I don’t mean personally screwed. It’s just business. So the picture didn’t get very good distribution but it got very good reviews. We played nineteen weeks in one theatre in Seattle.

JS: I have one last question. It’s about a role you were in. You played Bennett Cerf in Infamous, the film about Truman Capote. I was curious if you ever met Bennett Cerf and if you knew Capote?

This scene from the 2006 biopic, Infamous, about Truman Capote features Isabella Rossellini and Peter Bogdanovich as Bennett Cerf.

PB: Yeah, I knew Truman. I knew him, not well, but I’d met him a few times. I interviewed him when I was doing a piece about Bogart for Esquire. So I met him in 1963 and In Cold Blood hadn’t quite come out yet. Then I met him over the years numerous times. There’s a funny story I heard about Truman. It’s in my diary…I kept a diary for about five years during the Targets period. And somebody asked him if he knew Peter Bogdanovich and he said, “He directed Targets. How’s that for haut courant?”

I liked him very much though he was a sad figure toward the end. I’d meet him at parties and he’d be drunk and out of his mind and making no sense at all. Bennett Cerf I never met but I saw him repeatedly on What’s My Line? When I was cast in the part and Doug [McGrath] asked me to play it, I went to the Museum of Radio and Television and looked at some What’s My Line? episodes and made some notes about him and his accent. He had a very strange accent. He had kind of a high voice, a tricky voice – because I do Jerry Lewis and I do Cary Grant but his voice readings were somewhere in between. If I went a little too far it would sound like Jerry and I would have to pull it back and it would sound like Cary so it was tricky.

Other websites of interest:

https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/interview-peter-bogdanovich

https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2010/04/magnificent-obsession-200201

Who took the photo of Bogdanovich and Welles in the grocery store?

There is no photographer credited. This photo is all over the internet, on twitter and other media platforms.