When you consider movies made for children and/or family viewing, stories about horses constitute a large portion of the genre, especially in American cinema. My Friend Flicka (1943), Black Beauty (1947), The Story of Seabiscuit (1949), Snowfire (1957), The Sad Horse (1959) and The Black Stallion (1970) are just a few of the more famous titles and some of these have inspired remakes or sequels. Still, one of my favorite films in this category comes from France and is often overlooked today – Crin Blanc: Le Cheval Sauvage (English title: White Mane, 1953), written and directed by Albert Lamorisse (1922-1970).

This was only the director’s third effort (Banlieue [1947], a documentary short, was his first and was followed by the 1951 family drama, Bim, the Little Donkey) but it proved to be a critical and commercial success and launched his international film career. It was also the first Lamorisse film to explore some of his recurring themes and interests: the innocence of children, man (adults) as a destructive force, and the beauty and wonders of the natural world.

An offscreen narrator informs us at the start of White Mane: “In the south of France where the Rhone spills into the sea, there is an arid land called the Camargue.” This vast wetlands area is famous for its more than 400 species of birds but also for the wild Camargue horses which roam the marshes and sand dunes. It is here that the story of White Mane unfolds as he and his untamed companions roam free while avoiding capture by gardians (local herdsmen).

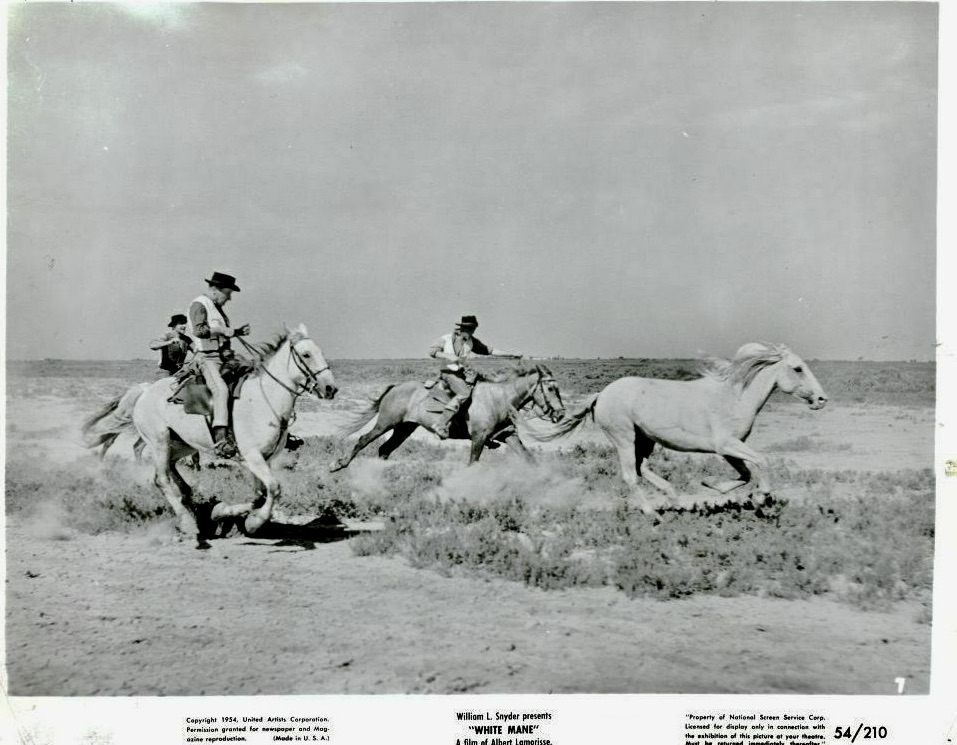

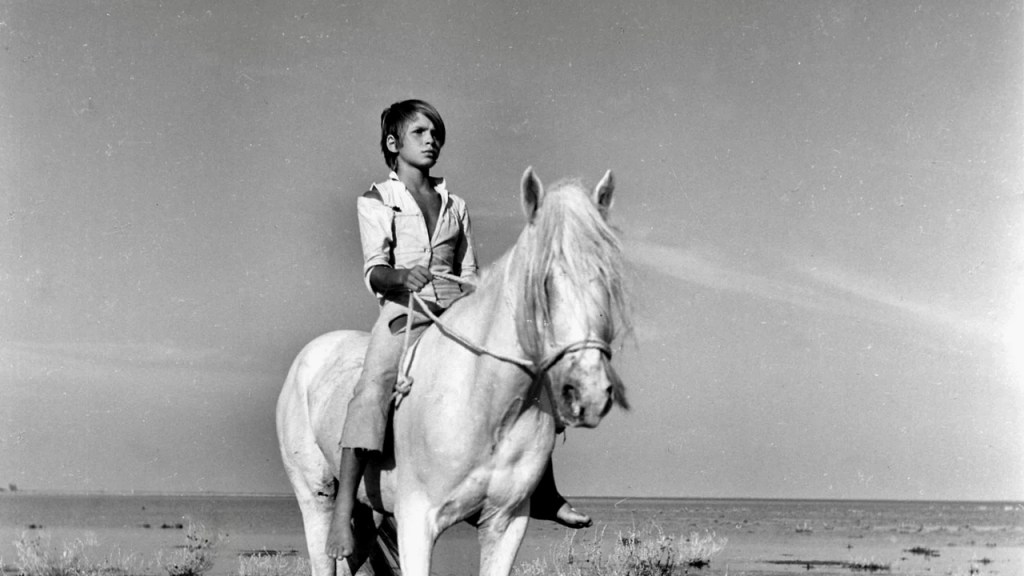

Folco (Alain Emery), a young fishermen who lives with his three-year old brother (Pascal Lamorisse) and grandfather (Laurent Roche), witnesses White Mane being hunted by four gardians one day and decides to befriend and protect the stallion. But Folco’s fantasy of taming and riding the white horse requires a great deal of patience, trust and physical endeavor.

White Mane is accompanied by minimal dialogue and narration (the French narration is by Albert Lamorisse, the English narration is written by James Agee) and a stirring dramatic score by Maurice Leroux with gypsy flamenco guitar accents. Yet, the most vivid and memorable portions of the film are purely visual and achieve a poetic lyricism that is grounded in reality by the documentary-like treatment of the characters and the Camargue region.

Unlike Walt Disney family-friendly fare, White Mane is not sentimental or formulaic and presents a world where children and animals are able to form a bond despite the corrupting influences of the outside world – in this case, the local herdsmen are a constant threat to the Camargue horses. A unique balance between a kind of magical realism and gritty documentary detail puts White Mane in a category of its own. Carroll Ballard’s film adaption of The Black Stallion comes close to this quality at times but Lamorisse’s film has a darker, underlying tone that is revealed in the ambiguous ending.

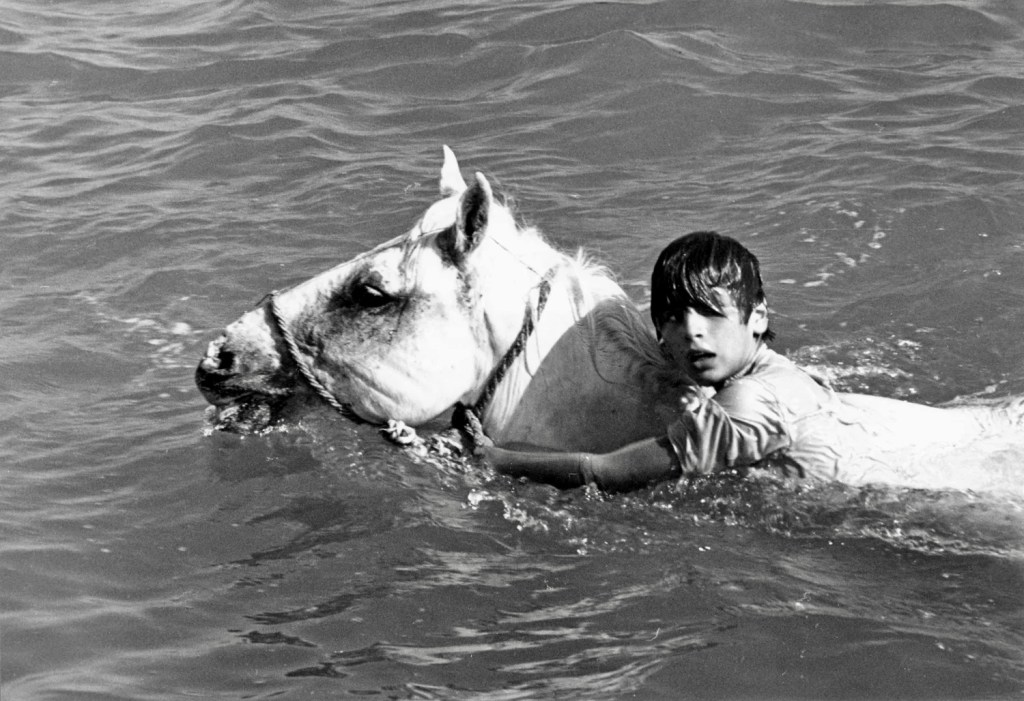

When Folco mounts White Mane at the finale, the duo try to escape the pursuing cowboys by plunging into the river and are swept out to sea. The narrator informs us: “…the young fisherman didn’t listen to the wrangler and his herdsmen who had lied to him before. He and White Mane vanished in the waves before their eyes. They swam straight ahead, straight ahead. And White Mane with his great strength carried his friend who trusted him to a wonderful place where men and horses live as friends, always.” As we see Folco and White Mane swimming into the distance, the viewer can either believe that the two reached a magical land or perished together in the sea – free at last.

One of the most impressive aspects of White Mane is the film’s pictorial beauty (the stunning black and white cinematography is by Edmond Sechan [That Man from Rio, 1964]) and the action sequences involving the horses. Alain Emery didn’t know how to ride a horse before filming began but you would never know it from watching him ride White Mane bareback in the second half of the film. Although a stunt double was used for Emery in some of the long shots of Folco being dragged across the marshes and mud plains by the horse, the young actor is clearly present in the astonishing scene where he and White Mane are trapped in the middle of a burning marsh and manage to escape. The sequence where White Mane battles another stallion for dominance of his herd is also intense and brutal as the two horses savagely bite each other, drawing blood.

If there is an American equivalent of White Mane, it would probably be Misty, the 1961 movie based on Marguerite Henry’s 1947 novel, Misty of Chincoteague. Set on an island near Virginia’s eastern shore, Misty has a setting very similar to White Mane with its sand dunes, marshes and abundant wildlife. The story, in which two children try to capture and tame Misty, also has an ending in which freedom is the only alternative for the wild horses. But Lamorisse’s film is the better movie due to its artistry and innovative editing (by Georges Alepee).

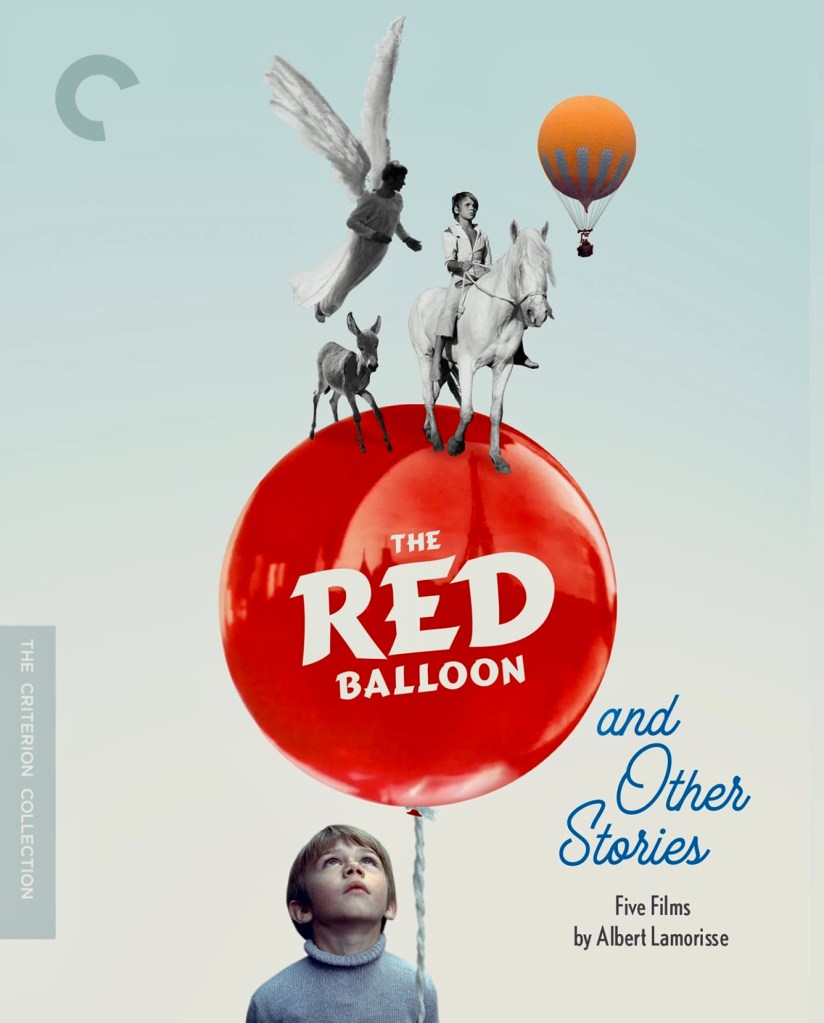

Lamorisse would go on to even greater success with his next film The Red Balloon (1956), which won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. Once again a lonely youngster develops an unlikely friendship (with a balloon) and at the end he is carried away from the world of uncomprehending adults by dozens of balloons. The Red Balloon is easily Lamorisse’s most famous movie but some critics and cinephiles prefer the director’s less whimsical White Mane, which has elements of a mythic fable.

Pauline Kael wrote that White Mane was “one of the most beautiful films ever made…a tragic fairy tale – about a boy’s love for a horse he alone is able to tame….The filmmaker was Albert Lamorisse; his intentions were clearly to achieve a piece of visual poetry – unlike most filmmakers who head that way he succeeded.” The film went on to win Best Short Film at the Cannes Film Festival and to garner a Best Documentary nomination from BAFTA.

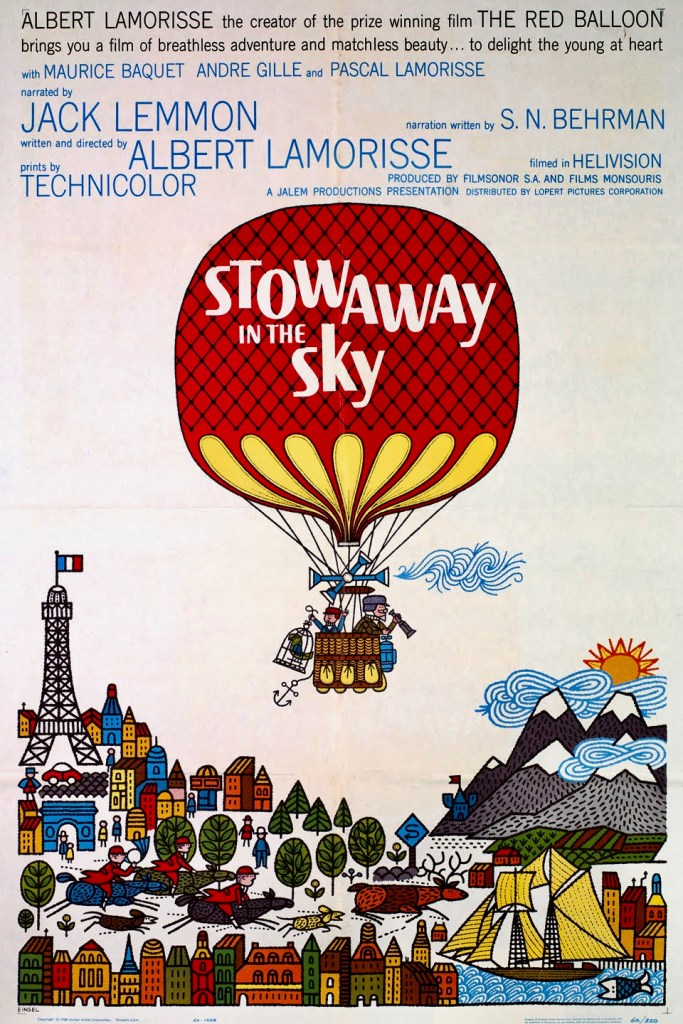

Director Lamorisse would continue to make shorts and features after the success of The Red Balloon such as the 1960 family adventure Stowaway in the Sky. And his expertise at using helicopters for cinematography efforts highlighted much of his later work but it also led to the director’s early demise. He died in a helicopter crash while filming Le Vent des Amoureux (English title, The Lovers’ Wind) in Iran in 1970. The film, an offbeat and poetic aerial documentary of the country’s landscape, was eventually completed by Lamorisse’s widow Claude and son Pascal and released in 1978.

White Mane has been released on various formats over the years including a stand-alone DVD from The Criterion Collection. A much better option is Criterion’s December 2023 Blu-ray release of The Red Balloon and Other Stories which includes White Mane along with Bim, the Little Donkey (1951), Stowaway in the Sky (1960), Circus Angel (1965) and numerous extra features.

Other links of interest:

https://vertipedia-legacy.vtol.org/milestoneBiographies.cfm?bioID=316

https://kids.kiddle.co/Albert_Lamorisse

https://antonalyptic.blogspot.com/2015/10/folco.html