When most baby boomers think of actor Robert Young, they probably recall his popular TV medical series Marcus Welby, M.D. (1969-1976) where he was the epitome of the kind, compassionate doctor or they remember Jim Anderson, the perfect dad in the all-American family sitcom Father Knows Best (1954-1960). He was also typecast as “Mr. Nice Guy” in most of his Hollywood films, playing cheerful romantic leads or the leading man’s best friend or some other debonair, noble or well-intentioned character who rarely made a strong impression compared to more assertive male leads like Clark Gable, Gary Cooper or Spencer Tracy. But there were several occasions when Young discarded his good guy image by playing shadowy characters, outright villains, or damaged human beings. Among these atypical casting choices, Young is most memorable in Alfred Hitchcock’s Secret Agent (1936) as an undercover spy, a budding fascist in The Mortal Storm (1940), a shellshocked and physically maimed war veteran in The Enchanted Cottage (1945), a complete cad and accused murderer in the underrated film noir They Won’t Believe Me (1947), directed by Irving Pichel, and an architect who is suspected of being a dangerous criminal in The Second Woman (1950).

Robert Young made his first credited screen appearance in the Charlie Chan mystery thriller The Black Camel in 1931 and was then signed by MGM where he worked steadily as a contract player up through the mid-1940s. He often complained in later years that MGM often gave him roles that Robert Montgomery (a bigger star at the time) had turned down. For Secret Agent (1936), an adaptation of a W. Somerset Maugham short story, MGM loaned Young to Gaumont in the U.K. and it was quite a departure from the breezy romantic leads he had played in Hollywood. Since this was a Hitchcock thriller set in the world of espionage during WWI, no one is who they pretend to be and everyone could be a spy in disguise. While Young is charming and flirtatious on the surface, he is a master of deception with ulterior motives. [Spoiler alert] He meets his demise in a climatic train wreck but not before killing the true villain of the piece – Peter Lorre as a deadly German agent. The film was an unexpected change of pace for Young but he made an even stronger impression four years later in a disturbing melodrama about the rise of fascism in Germany.

The Mortal Storm (1940), directed by the great Frank Borzage, is a cautionary tale about the xenophobia that swept through Germany in the thirties and triggered the rise of the Nazi party. Though it is structured as a romantic drama set in a small German village, the film’s turbulent background eventually occupies the foreground and overwhelms the story. At the beginning of the film Young is the fiancé of Freya Roth, played by Margaret Sullavan, but as he becomes swept up in the ideology of the Nazi party, he slowly becomes a threat to the Roth family and all non-Aryan members of the community. Young’s transformation from the ardent suitor to a hateful oppressor may be melodramatic but it’s a side of Young you always knew was there. Nobody can be that nice all the time and in this film his conversion to fascism allows him to finally release all that pent-up anger for being stuck in drab romantic roles all those years at MGM. He’s a frightening character and you genuinely fear for Sullavan and James Stewart when they flee the town at the tragic conclusion. It was due to The Mortal Storm that all future MGM films were banned by the German government for the reminder of WW2.

Young had another unlikely role in John Cromwell’s version of The Enchanted Cottage (1945), where he plays a disfigured WW2 veteran who has retreated from the world to live in seclusion on a vast estate. While there he meets and falls in love with Laura (Dorothy McGuire), a homely but kind young woman who assists the caretaker of the property. Based on a popular 1922 play by Sir Arthur Pinero, the film, which was first filmed in 1924, is the kind of romantic fantasy where the two main characters “magically” appear to each other as the beautiful souls they really are – minus the physical defects. Despite the sentimental and fantastical nature of The Enchanted Cottage, however, it is a long way from the lightweight, romantic fare Young had appeared in previously such as The Bride Wore Red (opposite Joan Crawford, 1937), Rich Man, Poor Girl (opposite Lana Turner, 1938) and Maisie (opposite Ann Sothern, 1939). The Enchanted Cottage comes off as more of a gloomy, almost morbid allegory compared to those films but Young always cited it as one of his favorite movies.

Still, the most surprising Robert Young role was yet to come in They Won’t Believe Me (1946), which might be my favorite performance of his. It also has a terrific supporting cast (Jane Greer, Susan Hayward, Rita Johnson) and is produced by Joan Harrison (a screenwriter for Hitchcock on four features and his TV series Alfred Hitchcock Presents). Young plays Larry Ballentine, a married stockbroker who is also a compulsive womanizer and liar, capable of embezzlement and other illegal business transactions. Told in flashback from a courtroom murder case, Ballentine emerges as a weak, amoral and highly ambitious guy who attracts women who sense a similar hunger and drive for success. His wealthy wife (Johnson) is aware of his many flaws but clings to him anyway and tries to manipulate his behavior through her purse strings. It doesn’t work of course and he plunges into one adulterous affair after another leading to a chain of tragic coincidences that land him in court, facing the death sentence.

Bad luck comes in spades in They Won’t Believe Me, and Young, like Tom Neal’s character in Detour (1945), seems doomed from the start. The ending is over the top but somehow appropriate considering everything that has gone before. And Young is completely convincing as the spineless, callow and self-absorbed Ballentine. He’s such a loser that you feel real empathy for him by the end of his miserable tale. It’s a long way from Marcus Welby and Jim Anderson but somehow you always knew something dark and disturbing was behind Young’s kindly smile.

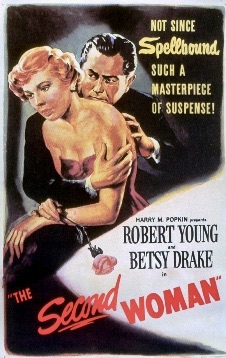

By the time, Young appeared in The Second Woman (1950), he was nearing the end of his film career and would only appear in three more features before transitioning into television. Once again, the actor plays against his genial stereotyped screen persona to portray a man who is becoming increasingly paranoid over a string of bad luck…or is he orchestrating incidents in preparation for a much worse crime? In this mostly forgotten psychological drama/mystery, Young is Jeff Cohalan, an architect suffering from depression. His spirits brighten considerably after meeting Ellen (Betsy Drake), a woman who is visiting his next door neighbor, but soon rumors about Jeff’s past begin to surface. And Ellen begins to wonder if Jeff had something to do with his late wife’s death from a car accident. The Second Woman, directed by James V. Kern, is full of red herrings like Hitchcock’s Suspicion (1941) or Spellbound (1945) and Ellen ends up playing detective to sort out the truth. While the suspicion that Jeff might be a dangerous criminal is teased throughout the narrative, the finale exposes the real culprit, leaving Jeff and Ellen free to go off together. Still, the film is much darker than the fluffy Robert Young comedies that preceded it – And Baby Makes Three (1949) with Barbara Hale and Bride for Sale (1949) starring Claudette Colbert – but it was Young’s last stab at a character that was the opposite of the wholesome, all-American leads he usually played.

In his entertaining reference tome The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson wrote this about Young: “So long on the slopes of the industry, he learned to take nothing too seriously, and that showed – as lightness, indifference, or amusement. King Vidor once called him “a director’s dream…Popular regard, which sets it idols aside in the awe-enthralling class, sometimes demands a quality of neuroticism which Bob healthily doesn’t possess.” The truth, however, is that Young often expressed his bitterness at being typecast or forced to do unwanted films and his unhappiness may have contributed to his lifelong depression and a problem with alcohol. At one point in 1991 he even attempted suicide but he bounced back from that to become a tireless advocate for mental health counselling.

Young lived to the ripe old age of 91 and left behind a legacy of more than 100 film and TV credits. He never received an Oscar nomination for any role but he was certainly worthy of one. 1942 was probably his peak year in Hollywood; that was the year he won the National Board of Review Best Acting award for his work in H.M. Pulham, Esq., Joe Smith, American and Journey for Margaret. Other career highlights include Northwest Passage (1940), an epic adventure directed by King Vidor, Claudia (1943) opposite his frequent co-star Dorothy McGuire, and Crossfire (1947), a controversial film noir directed by Edward Dmytryk. It is true that Young will probably always be associated with his upbeat, kindly father figures on TV but his rare forays into darker territory are impressive and highly recommended for the curious.

Other links of interest:

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3252/robert-young

https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/people/robert-young

https://loveletterstooldhollywood.blogspot.com/2020/09/ann-sothern-and-robert-young-cant-stop.html

https://www.outofthepastblog.com/2021/07/they-wont-believe-me-1947.html