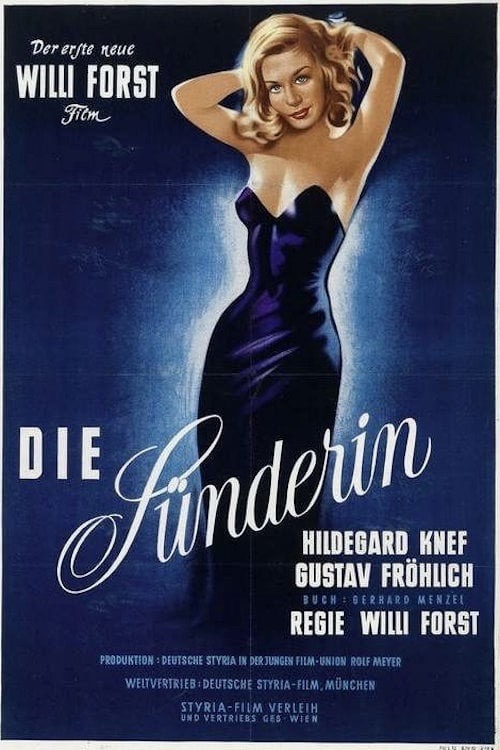

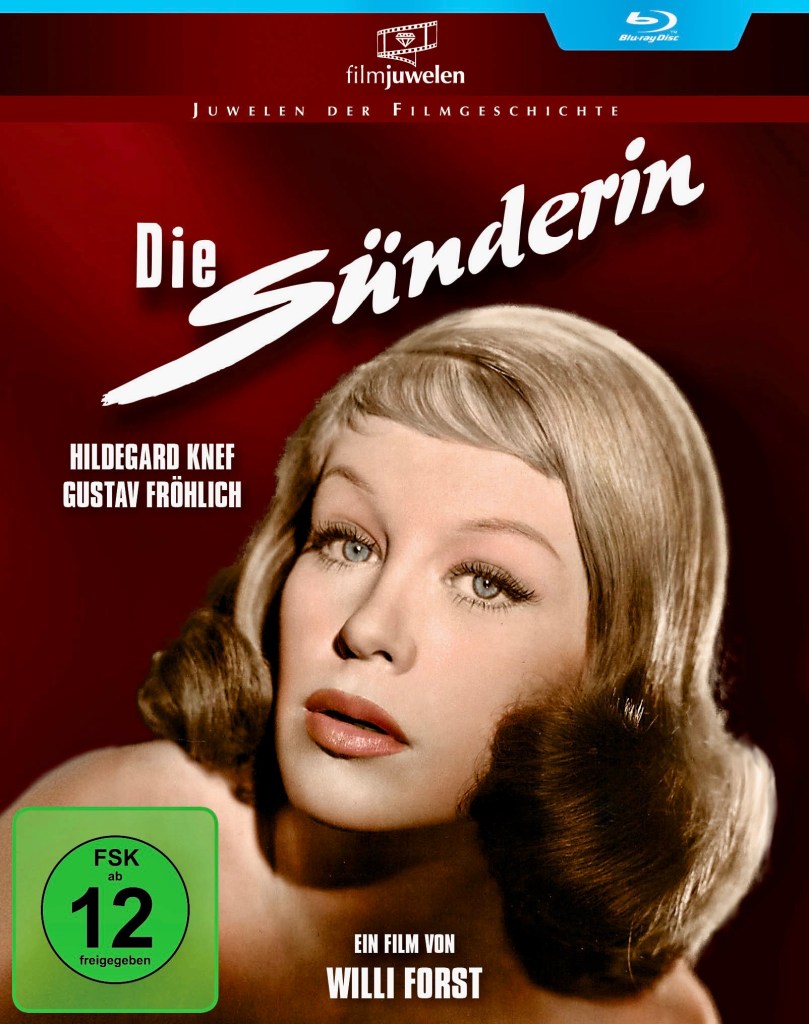

Sometimes an offscreen scandal can kill or severely hamper a career (Fatty Arbuckle, Ingrid Bergman, Rose McGowan, etc.) or help bolster it as in the case of Mary Astor, Hedy LaMarr or Elizabeth Taylor. But what if the scandal is the film itself as in The Moon is Blue (1953), Baby Doll (1956) or Last Tango in Paris (1972)? That kind of notoriety can play out in different ways affecting the careers of the featured stars in a negative or positive way. A famous example of the latter is Die Sunderin (English title: The Sinner, 1951), a West German melodrama from Viennese director Willi Forst in which two social outcasts embark on a love affair which brings them true happiness and spiritual redemption after years of misery. The film created a public outcry in Germany due to a nude scene featuring the popular female star, Hildegard Knef. It might seem much ado about nothing today but at the time the typically conservative German moviegoer was offended. More importantly, it didn’t hurt Ms. Knef’s career at all and may have helped launch her international career. She was invited back to Hollywood the same year (where she had previously been under contract), made a few high profile films, and then returned to Germany where she not only resumed her film career but also became a renowned chanson-singer in the style of Marlene Dietrich, a mentor and friend.

Knef’s brief nude scene in The Sinner is tastefully done – she is posing for a painting – but the movie’s plot might have been the real reason German audiences were shocked. Told in flashback, Forst’s tale is one of suffering, sacrifice and perseverance for Marina (Knef), a prostitute, and her lover Alexander (Gustav Frohlich), an alcoholic painter with a terminable brain tumor. Since Marina is narrating the story, the focus is mostly on her gradual descent from innocent 14-year-old to bohemian party girl to streetwalker but she is finally redeemed by her selfless love for a gifted artist whose physical pain has driven him to drink. Together they try to make a new life together with Marina financing Alexander’s career by hustling tricks but the painter’s alcoholic rages and suicidal impulses are a constant source of conflict. It soon becomes apparent that unless Alexander undergoes a risky brain operation, he will go blind and die.

The Sinner, which spans a time period from the early thirties to a few years after WW2, is a masochistic romantic fantasy, and is often as overwrought and preposterous as one of Douglas Sirk’s delirious soap operas like his 1954 remake of Magnificent Obsession. Unlike that film, however, The Sinner does not fade out on a note of spiritual uplift with the promise of eternal happiness for the main couple. [Spoiler alert] It does flirt with the possibility of a happy ending – Alexander does undergo the brain operation successfully and becomes a successful and famous painter. But Forst is more interested in depicting the kind of love that can transcend any obstacle, even death. When Alexander’s brain tumor returns and he goes blind, there is only one solution for the lovers. They celebrate their life-changing union with a champagne toast spiked with an overdose of veronal (a lethal sedative). A rollercoaster love affair that ends in a suicide pact is not what most audiences expect from a movie romance but The Sinner wallows in a kind of poetic fatalism and despair that was almost palpable in Germany in the immediate post-war years.

German audiences who were upset by The Sinner might have taken offense at Knef’s nude scene but they might have been more upset at being reminded of the demoralizing post-war years when people were starving, cities were in ruins, the black market was thriving and many unemployed women were forced into prostitute to merely survive. They were also probably upset that Marina and Alexander had both come from wealthy, upper-class backgrounds but had fallen into the lowest rung of society due to their own actions and this was unforgivable to moralistic viewers.

The Sinner certainly stirred up considerable controversy. Cardinal Frings of Cologne pointed to the film as “an example of the moral decomposition of Germany” and Catholic clergymen in some areas threw stink bombs into theaters that showed the film, creating problems for the theater owners. Nevertheless, it was a box office hit in Germany but it hasn’t aged as well as some other critically acclaimed films from the same era such as Peter Lorre’s solo directorial effort, The Lost One (1951) and Helmut Kautner’s The Last Bridge (1954).

At the same time, The Sinner is worth seeing for several reasons. The moody black and white cinematography of Vaclav Vich (Erotikon, The Mistress) has a velvety film noir look that captures the grim reality of post-war Munich and Hamburg. There is a wonderful sequence chronicling Marina and Alexander’s idyllic vacation in Italy where you get to see relatively deserted and tourist-free imagery of Venice and Positano. But the main reason to see the film is for Knef’s luminous performance as the self-sacrificing heroine. She can certainly rival Bette Davis or Joan Crawford when it comes to grand diva histrionics but she is even more impressive when she plays the seductive siren or self-destructive hedonist. Her mixture of vulnerability and hard-edged cynicism is just right for Marina and there are occasional glimpses of a bitter, self-deprecating sense of humor such as a scene where she returns to prostitution to raise money for Alexander’s operation, equating her indiscretion with “a stumble in the mud.”

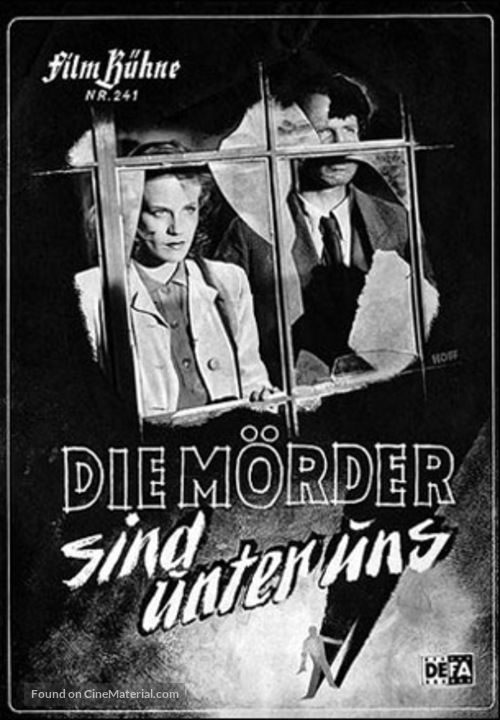

Knef was one of the most important female stars of post-war German cinema and her life story would make a fascinating biopic with so many improbable twists and turns that even a work of fiction couldn’t rival it. At age 17, she got her start with Ufa Studios as a painter and animator during WW2. Her personal relationship with Ewald von Demandowsky, who worked in Reich Propaganda at Minister Joseph Goebbels’s film office, helped Knef launch an acting career. During the closing days of the war, she followed von Demandoswky to the eastern front, disguised as a man. Although she was captured by the advancing Polish army, she escaped from prison and returned home, where she established herself as a rising film star. Her fourth feature film, Die Morder sind unter uns (English title: Murderers Among Us, 1946), for the East German film company Deutsche Film (DEFA) is considered her breakthrough film and still regarded as one of her finest performances, playing a concentration camp survivor who returns to her home in war-torn Berlin.

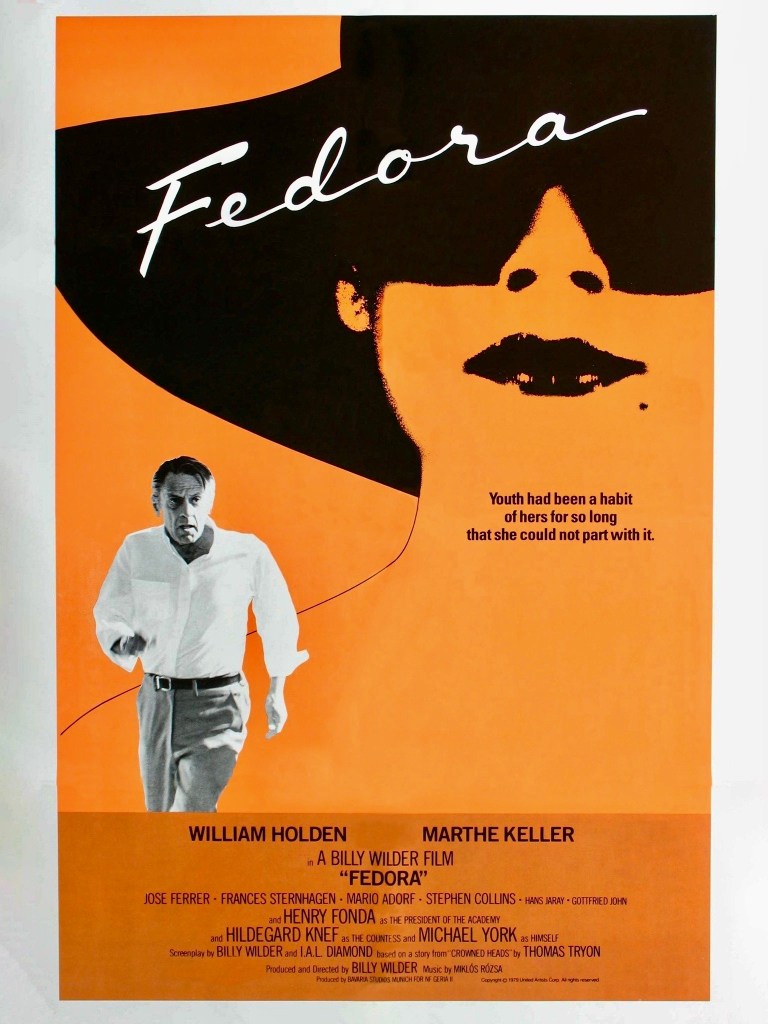

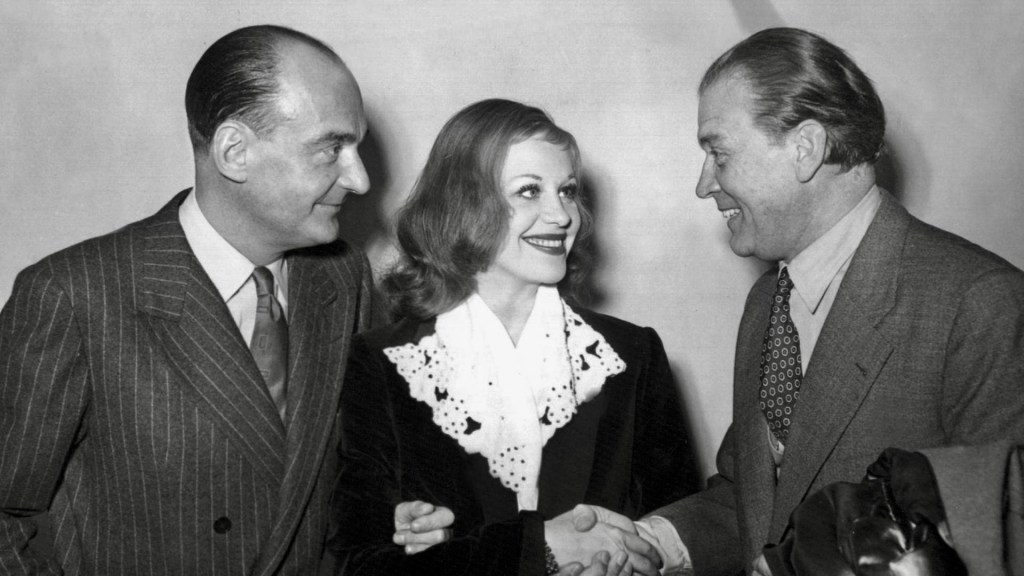

Movie mogul David O. Selznick lured Knef to Hollywood in 1947 and put her under contract, changing her last name to Neff. Unfortunately, she didn’t work for almost two years due to her constant rejection of unworthy scripts and the studio’s nervousness about her past association with Goebbels. An award-winning performance in Rudolf Jugert’s romantic comedy Film Without a Name (1948) and The Sinner helped revive her film career and Hollywood came calling again, casting her in Decision Before Dawn (1951), Diplomatic Courier (1952) with Tyrone Power and The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1952) featuring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Susan Hayward. Some of Knef’s more memorable roles after this include the sci-fi melodrama Alraune (1952), Carol Reed’s The Man Between (1954), Rolf Thiele’s Lulu (1963), Everyone Dies Alone (1976), a WW2 era anti-Nazi drama, and Billy Wilder’s Fedora (1978).

The actress’s parallel career as a stage actress reached a peak in the 1950s when Noel Coward cast her in a Broadway production of his musical Silk Stockings. It was a huge success that resulted in a run of almost 500 performances. Later in the early sixties, Neuf embarked on a singing career, writing her own songs and enjoying pop chart success with singles like “It Shall Rain Red Roses for Me,” “From Here On It Got Rough” and her rendition of “Mack the Knife.” Neuf even found time to pen two autobiographies, The Gift Horse: Report on a Life (1970) and The Verdict (1975), an account of her struggle with breast cancer. Her later years, in fact, were often plagued by poor health and a long series of surgeries (she had 56 in all!). She died in February 2002 at age 76 from a lung infection.

Like Knef, her co-star Gustav Frohlich also had connections to the Third Reich via the German film industry. He was multi-talented as an entertainer and could sing, dance, write screenplays and even direct but he was most famous as a stage and film actor. Most movie buffs know him as Freder, the hero of Fritz Lang’s masterpiece Metropolis (1927) but he was more popular in Germany for playing debonair-men-about-town in the Maurice Chevalier mode in musicals and romantic comedies. His career didn’t suffer during Hitler’s reign and he was one of the top male stars of his era along with Hans Albers, Heinz Ruhmann and Willy Fritsch. However, it was rumored that he was briefly blacklisted for slapping Joseph Goebbels in a jealous rage over actress Lida Baarova, to whom Frohlich was engaged, but there are no reliable sources to confirm this.

By the time Frohlich starred in The Sinner he had been relegated to supporting roles but his role as Alexander offered him a rare dramatic part. Even though his tortured artist/self-pitying alcoholic character was a well-worn cliché, he managed to bring some genuine pathos and disturbing intensity to his scenes, especially the touching finale when he realizes he has gone blind.

The Sinner also turned out to be a rare dramatic vehicle for director Willi Forst, who like Frohlich had been a popular singer and musical star in his early career. He moved into the director’s chair in 1933 and became one of the most significant directors of Austria in the 1930s, specializing in a type of light comedy and musical melodrama known as Wiener Filme. His most popular work was a trilogy consisting of his directorial debut, Leise flehen meine Lieder (1933), a love story about composer Franz Schubert and Countess Esterhazy, Wiener Blut (1942), a romantic comedy set in Vienna circa 1815, and Wiener Madeln aka Viennese Maidens (1949), a musical biography of Austrian composer Carl Michael Ziehrer. Like Knef and Frohlich, Forst was able to work within the Goebbels’ controlled film industry by avoiding political statements and focusing on light entertainments that nonetheless contained personal insights into Austrian culture and history which was worlds away from the Nazi propaganda machine.

Forst would later remark in an interview by Gertraud Steiner in Film Book Austria, “I never wasted much thought on the kind of films I was making. They came about by themselves, born of my relief at no longer having to “reproduce,” and of the growing pressure exerted by the Nazis. My native country was occupied by the National Socialists, and my work became a silent protest. Grotesque though it may sound, it is true that I made my most Austrian films at a time when Austria had ceased to exist. I hit upon exactly the things people yearned for: distraction, joy. What I began doing – I would again say, with almost unerring accuracy – turned into a program, was fashioned ever more consciously into a program. Of course, we couldn’t go looking for what we wanted in the present, which is why virtually all of my films are set in the past. I created films reviving the spirit of an age in which charm, sophistication, delicacy and courtesy were important qualities. I freely concede that this was the product not just of a mental attitude, but also and to a significant degree of the need to ward off the interference of the Reich Propaganda Minister.”

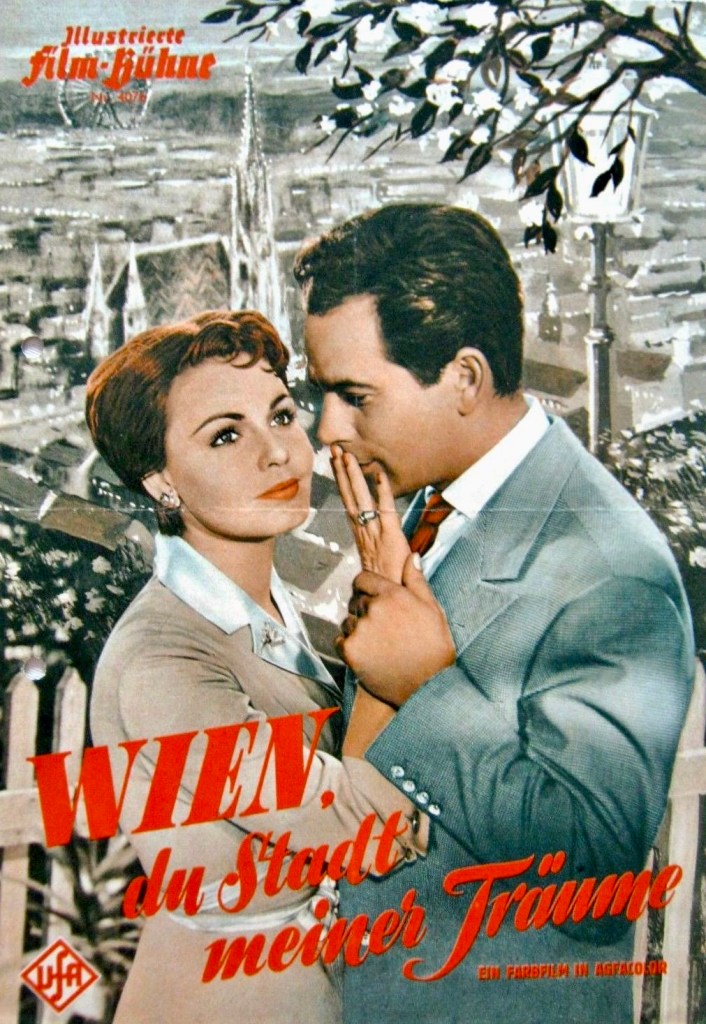

When The Sinner was released, Viennese audiences in particular were surprised, not only because it was a German production with a German star, but also because it was such an unexpected departure for a director who specialized in period pieces steeped in Viennese culture. The film was also unabashedly frank in its treatment of prostitution, suicide and euthanasia. Despite its financial success, The Sinner proved to be Forst’s solo foray into a form of neorealism noir and he returned to lightweight romantic comedies and musicals for his final films such as Miracles Still Happen (1951), The Three from the Filling Station (1956) and Wien, du Stadt meiner Traume (1957), the film poster is pictured below.

The Sinner is not available on DVD or Blu-ray in the U.S. but if you own an all-region Blu-ray player you can purchase the February 2019 DVD release of the film from Filmjuwelen (Alive AG) from online sellers (no English subtitles option). You can also stream for free a decent print of the film on Youtube (no subtitles) or even better, the restored, subtitled edition of the movie from Deutsches Filminstitut on the Cave of Forgotten Films website.

Other links of interest:

https://www.umass.edu/defa/people/2215

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2002/feb/02/guardianobituaries.filmnews

https://www.dw.com/en/goodbye-to-a-legend/a-433056

https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/cinema-rubble-movies-made-ruins-postwar-germany