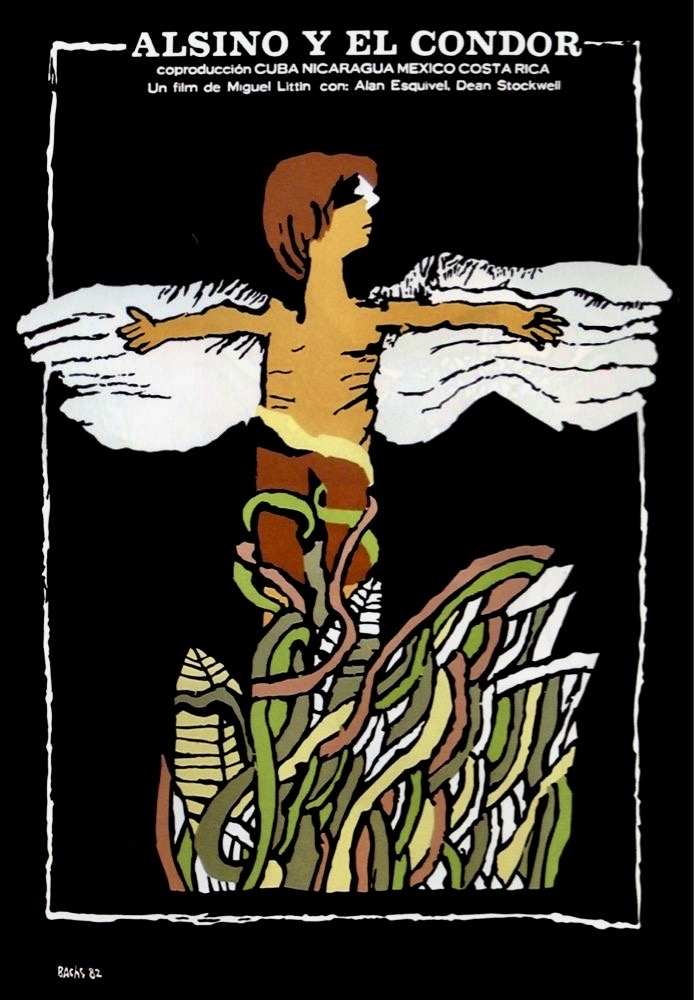

In 1979, the Somoza dictatorship of Nicaragua was overthrown by the FSLN (Sandinista National Liberation Front) and it led to a decades long war with the country’s National Guard and the U.S. backed Contras aligned against the left wing Sandinista forces. The conflict raged until 1990 and it was a terrible time for the people of Nicaragua, especially the peasants and native communities like the Miskito in rural areas. Although several documentaries have been made on the subject over the years such as Werner Herzog’s Ballad of the Little Soldier (1984), there have been few high-profile dramatic features about the conflict. One of the rare exceptions is Under Fire (1983), Roger Spottiswoode’s intense drama about three journalists (Nick Nolte, Gene Hackman and Joanna Cassidy) covering the final days of the corrupt Somoza regime. Another worthy contender is Alsino and the Condor (1982), directed by Miguel Littin, which was filmed on location in Nicaragua and was Oscar nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film. Unlike the more realistic approach of Under Fire, Alsino and the Condor functions more as an allegory and was loosely based on Pedro Prado’s famous 1920 novel Alsino about a young boy who dreams of flying like a bird.

Unlike the original novel, the young protagonist of the film (who is supposed to be ten years old), is trapped in the middle of a revolution but, at first, he is more absorbed in his own fantasies and inner thoughts than the reality of what is happening in front of his eyes. Alsino (Alan Esquivel) lives with his grandmother (Carmen Bunster) and she has filled his head with folklore and stories about his long deceased grandfather. The boy dreams constantly of flying and, during an encounter with Frank (Dean Stockwell), a U.S. army officer, he gets to ride in Frank’s chopper. The experience impresses him but he still fantasizes about using his own arms for wings as opposed to a man-made machine.

As a result, he scales a tall tree on a windy day and attempts to launch himself into the sky with disastrous results. He permanently injures his back in the fall and soon earns the nickname “Hunchback” due to his misshapen body. The experience transforms the dreamer into a more self-aware adolescent who begins to experience and react to the oppressive forces that are uprooting his family and fellow villagers. By the end of Alsino and the Condor he has picked up a rifle and joined the rebel forces against the military aggressors.

Inspired by the writings of Columbian novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, director Littin juxtaposes Alsino’s dreamlike state and moments of magical realism against the harsh realities of the Nicaraguan Revolution where most of the victims were villagers in rural areas like the jungle. Many of them were poor farmers and not political or well educated. As things begin to fall apart, the film veers back and forth from the lyrical to the horrific as Alsino transforms from a passive observer to an activist.

Alsino and the Condor casts a hypnotic spell from its opening scene set to the sound of whirling helicopter blades (that invokes Walter Murch’s sound design for 1979’s Apocalypse Now). Even if most of the characters emerge as little more than archetypes in an allegory, the narrative retains the viewer’s interest with vivid details about Alsino’s journey to self-awareness like his brief sojourn with a peddler who sells love birds and a visit to a brothel where a teenage prostitute cuddles with him like a mother. Alsino could very well be a modern-day Candide but his character often remains inscrutable and is not a fully developed protagonist. Littin’s film also treads a fine line between the subtle and the heavy-handed.

Dean Stockwell, for example, stands out as an exaggerated version of the angry, Pro-Hawk American officer with a scorched earth policy. When he describes his policy of aggression to his Nicaraguan allies and fellow troops, he represents the worst kind of ugly American, meddling in the affairs of a country he doesn’t understand. “To ensure efficiency,” he promises, “we have to have constant surveillance of the population by the police, by informers, by the installation of modern listening devices, by data processing, etc., etc., and this will be done.”

In a later scene, Frank’s unhinged psyche is exposed when he gets drunk and starts spouting things like “you’re either a communist or you’re not.” As he winds down into incoherence, he starts singing the Dean Martin pop hit, “Everybody Loves Somebody Sometime.” He perfectly represents the type of U.S. soldier and C.I.A. officer that was sent to help the Nicaraguan National Guard suppress and dominate the rural population of their country.

At the time he made Alsino and the Condor, Stockwell was on the verge of a career renaissance. He had just co-directed and starred in Neil Young’s bizarre, unreleasable musical fantasy Human Highway (1982) but his career was given a boost by his performance in Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984) and then director David Lynch turned him into a cult icon with his roles in Dune (1984) and Blue Velvet (1986). His winning streak continued with an Oscar nomination (his first and only) for Best Supporting Actor in Jonathan Demme’s Married to the Mob (1988). He also popped up in critic favorites like Francis Ford Coppola’s Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988) and Robert Altman’s The Player (1992) while reaching an even wider audience in the popular sci-fi TV series Quantum Leap (1989-1993). For his role in that, he received four Emmy nominations for Best Supporting Actor.

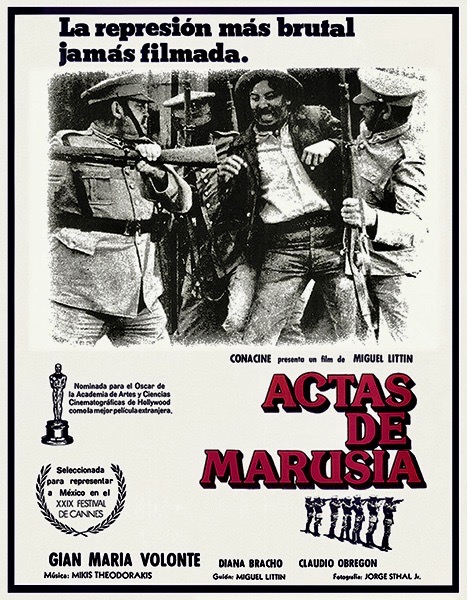

As already mentioned, Alsino and the Condor was Nicaragua’s official entry for Best Foreign Language Film for the Academy Awards (their first and only nomination to date). What is ironic is that most of the cast and crew were not from Nicaragua. Director Littin is from Chile but, like most of his fellow filmmakers from that country, had to flee elsewhere during the brutal military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. He was already considered a political subversive by Pinochet’s regime for Letters from Marusia (1975), his damning critique of the Chilean government’s suppression of a mine workers’ strike. Littin would go on to make such critically acclaimed works as El Recurso del Metodo (1978), Tierra del Fuego (2000) and La Ultima Luna (2005).

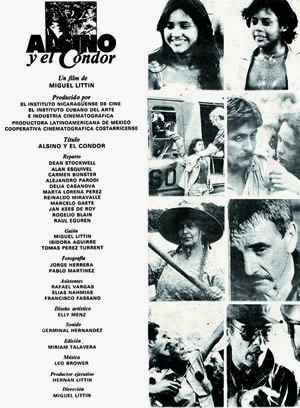

Most of the other cast and crew members of Alsino and the Condor were from countries like Mexico, Cuba and Argentina such as Carmen Bunster in the role of Alsino’s grandmother. The film’s evocative score is by Afro-Cuban composer Leo Brouwer and combines lush orchestration with strident dramatic passages. The movie’s main theme even seems influenced by the music of French composer Erik Satie. Brouwer is best known to most film buffs for his work on Like Water for Chocolate (1992) & several films for Cuban director Tomas Gutierrez Alea like Memories of Underdevelopment (1968) & The Last Supper (1976).

Alsino and the Condor received a number of glowing reviews upon its release in 1982 from critics like Roger Ebert and Francis Dickinson of Time Out who wrote, “The delightful Esquivel brings to the title role a fragile passion around which the Chilean film-maker Littin conjures an archetypal South American world of enchantment (the grandmother and her chest of secrets, the prostitute and the bird man, familiar from the writings of García Márquez and others) which can absorb intrusive realities as easily as the ever-present verdant jungle.”

Littin’s film is open to various interpretations but critic Sara Corben de Romero’s critique is quite revealing: “The very obvious allegories here are the illusion of liberty through flying, and real dictatorial oppression and North American aggression expressed by the helicopter. Cultural domination is expressed by Alsino’s wanting to possess the foreign object, the helicopter—even though it represents aggression. The film is full of symbols—in fact it could be said that there is not one real character in the film, merely symbols and emblems. There are birds unable to fly because their wings have been clipped, and Alsino becomes hunchbacked because he falls from a tree and only then begins to see things in a different light.”

Alsino and the Condor was a difficult film to see for many years but it finally appeared on DVD in September 2017 from the independent distributor Mr. Fat-W Video. It has no extra features and is certainly due for a Blu-Ray upgrade.

Other links of interest:

http://www.filmreference.com/Films-A-An/Alsino-y-el-Condor.html#ixzz1Pw6nthZA

https://screenanarchy.com/2010/02/psiff10-dawson-island-10-interview-with-miguel-littin.html

https://stockwellsassies.tripod.com/articles/Dean_Stockwell_Interview.html

https://stockwellsassies.tripod.com/articles/Dean_Stockwell_a.html

https://www.filmcomment.com/article/interview-dean-stockwell-blue-velvet-dune-patrick-mcgilligan/