In Japanese cinema, the samurai film can be many things. It can be a ghost story (Ugetsu, 1953), a rousing adventure (The Hidden Fortress, 1958), a tragic romance (Gate of Hell, 1953), a sweeping historical epic (Tales of the Taira Clan, 1955), a Shakespeare adaptation (Throne of Blood, 1957) or even a revenge saga (Chushingura, 1962). The latter is my favorite sub-genre in the category and the best samurai revenge films are usually driven by the avenger’s sense of honor being defamed and/or moral outrage at personal injustice. This is certainly the motivation behind the heroine of Lady Snowblood (1973), played by Meiko Kaji, and its sequel, Lady Snowblood 2: Love Song of Vengeance (1974). It is also the central premise of Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (aka Seppuku, 1962), which is more doom-laden and brooding than the kinetic action of the Lady Snowblood films but nevertheless explodes in a bloody, sword-wielding finale. But if you want to go deeper, darker and crueler, it is hard to top Toshio Matsumoto’s Demons (aka Shura aka Pandemonium, 1971) for pure malice.

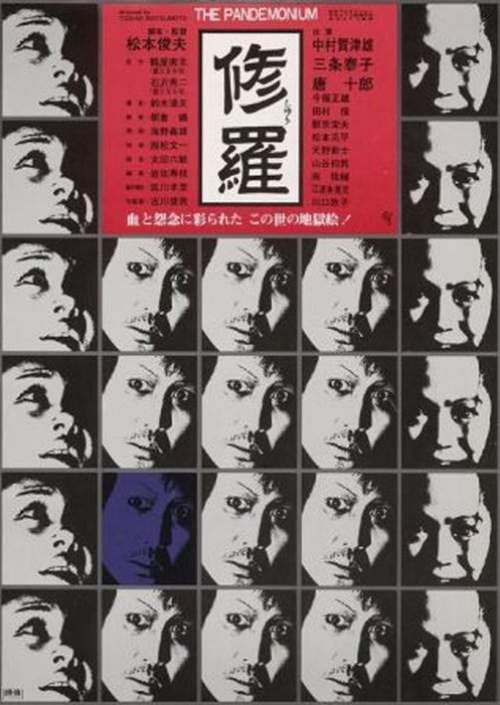

A scene from avant-garde filmmaker Toshio Matsumoto’s offbeat samurai tragedy, Demons (1971 aka Shura aka Pandemonium).

Relatively unknown compared to more famous samurai revenge films, Demons is a remarkable exercise in nihilism that is so breathtakingly grim that it becomes undeniably compelling. Unusual lighting effects, the stunning black and white cinematography of Tatsuo Suzuki and an unsettling sound design add to the film’s cumulative power along with Katsuo Nakamura’s haunting performance in the lead role.

The sun sets and takes all of the color with it as Toshio Matsumoto’s Demons (1971) plunges you into a world of darkness.

Demons opens with the sun setting beneath a crimson sky. It is the only time you see any color before the movie descends into total darkness punctuated by sparse usage of theatrical lighting effects. Right from the start, a sense of paranoia pervades the film as Gengobe (Nakamura), a Ronin warrior who has fallen on hard times, flees a group of shadowy lantern bearers. He takes refuge in his home and is greeted by Koman (Yasuko Sanjo), a geisha who has been his lover for several years. He sends her away and welcomes Hachiemon (Masao Imafuku), his faithful servant, who brings his master good news. The 100 ryo Gengobe desperately needs to join the 47 Ronin in a vendetta that will restore his and his clan leader’s honor has been raised by former allies of the currently impoverished samurai. This change in luck is soon thwarted by Koman’s unexpected return – or was she listening outside? – and her confession that she is to be married to a suitor who intends to buy her from her brother Sangoro (Juro Kara) for 100 ryo.

Koman (Yasuko Sanjo, left) and Gengobe (Katsuo Nakamura) in a rare moment of intimacy in Toshio Matsumoto’s horrific revenge drama, Demons (aka Shura aka Pandemonium, 1971).

[Spoiler alert] Gengobe is torn between his passion for Koman and the more honorable obligation but he ultimately makes the wrong decision and is betrayed. His reaction seals his fate and sets him on a course of bloody vengeance that ends with a bitterly ironic sting in the tail. We’re not talking about a noble figure here but someone who has already fallen from grace. Once known as a respected samurai named Soemon Funakura, he is now living under a false identity in impoverished circumstances. Gengobe is the epitome of an anti-hero, a wastrel whose vices have landed him in his current predicament. What’s worse is his impulsive nature which is easily manipulated by his enemies.

Hachiemon (Masao Imafuku) is the only character in the samurai tragedy Demons (1971) that is not deceptive or traitorous.

Almost every character in Demons is unsympathetic and devious with the possible exception of Hachiemon, who is so selfless in his sacrifices for his master that he becomes annoyingly obsequious. You could even blame Hachiemon for the tragedy that unfolds because his procurement of the 100 ryo is the trigger for a maniacal plot masterminded by Koman and Sangoro. Not only are they not brother and sister, they are married with a baby.

Koman (Yasuko Sanjo) with her baby and husband Sangoro (Juro Kara) are fearful of unexpected visitors in Demons (aka Shura aka Pandemonium, 1971), directed by Toshio Matsumoto.

These cynical opportunists exploit anyone to achieve their means and their true intentions are suspect as soon as they make their appearances in the story. Koman, in particular, is memorably heartless. When Sangoro asks her if she ever felt a smidgen of affection for Gengobe, she laughs and says, “Don’t be silly. A geisha lives a life of lies.”

Koman (Yasuko Sanjo, center) begs her dfamily to release her from an arranged marriage to a man she doesn’t love in Demons (aka Shura, 1971).

Koman and Sangoro’s accomplices in crime, including Koman’s brother, are equally contemptible and you long to see all of them suffer horribly for orchestrating Gengobe’s ruin, even if he brought it on himself. But when the revenge begins – and it is slow, painful and bloody – the result is not pleasurable in the ways of a popular genre thriller like Taken (2008) where Liam Neeson decimates, one by one, the Albanian sex traffickers who kidnapped his daughter. Instead it is nightmarish and unnerving and crosses over into extreme horror territory at times, conjuring up the anxiety-producing dread of something like Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left (1972). Yet this is no exploitation film but a brooding, artfully designed cautionary tale which might be the most effective indictment of revenge ever made.

A severed hand is first seen as a foreshadowing hallucination but later becomes a reality in Demons (aka Shura, 1971), directed by Toshio Matsumoto.

Grim it may be but there is a hypnotic quality to the fatal trajectory and part of the fascination is due to Matsumo’s tautly constructed narrative which is accented by startling visual flourishes such as scenes that begin as reality, only to be revealed as premonitions of future events envisioned by Gengobe. Gruesome images like a severed hand or head are more typical of the horror genre and there are supernatural touches as well such as a trek through a graveyard in which the ghosts of Gengobe’s victims call out to him. And in the course of the film, Gengobe loses his humanity and becomes a stalking wraith, his face hidden beneath a straw hat, until he chooses to reveal his malevolent face.

The ghost of a slain woman taunts the samurai who murdered her in a graveyard in Demons (aka Shura, 1971).

The death scenes (including the shocking murder of a crying baby) play out as gruesome tableaus which are all the more unsettling because of the beautifully stylized black and white art direction. In the end, revenge devours everyone, even the perpetuators. There is no release or catharsis in payback, just a soul-crushing numbness.

Gengobe (Katsuo Nakamura) spies on his mistress and her family in a tense discussion about marriage which turns out to be a staged event in Demons (aka Shura aka Pandemonium, 1971).

Aptly titled, Demons is a unique one-off for Matsumoto who is better known for his experimental shorts and avant-garde video works. Funeral Parade of Roses (1969), a gay reworking of Oedipus Rex set against the backdrop of political unrest in ‘60s Japan, is probably his best known feature film and employs some of the “neo-documentarism” techniques he used in exploring post-war Japanese society in other works. On the surface, Demons may look like a classic samurai period piece but the film’s dark, deeply pessimistic tone and hallucinatory nature stand apart from other samurai dramas and even Kobayashi’s Harakiri looks conservative in comparison.

Koman (Yasuko Sanjo) pretends to be a helpless geisha trapped by circumstances but she is much more cunning and dangerous than that in the samurai revenge film, Demons (1971).

Last but not least, Katsuo Nakamura is unforgettable as the doomed Gengobe, managing to be both frightening and pitiable at the same time. Although not as well known in the U.S. as other samurai stars like Toshiro Mifune and Tatsuya Nakadai, Nakamura is a highly regarded actor in his homeland with numerous awards for performances in such films as Tomotaka Tasaka’s Lake of Tears (aka Umi no koto, 1966) and Seijun Suzuki’s Kagero-za (1981).

Even though the film was made almost 50 years ago, Demons has slowly acquired a well deserved cult following and it continues to be re-appraised as a key film in ‘70s Japanese cinema, which was not the case when it was first released. Vincent Canby of The New York Times panned the film in a tone-deaf review that dismissed it as “an expensive film school exercise.” He goes on to say it “wears the furrowed brow of a 10-year-old boy struggling to recite “Thanatopsis” without the vaguest idea what he’s saying…the tale of rage transformed to madness seems closer to farce than tragedy…The style is soft, bogus, essentially frivolous…” Frivolous? Hardly. A farce? Only if you have a really sick sense of humor.

Unfortunately, anyone interested in seeing Demons is not able to judge for themselves because the film is not currently available on any format in the U.S. If you are lucky, you might be able to catch a repertory screening of it someday at the Japan Society or the Museum of Modern Art in New York City or some similar venue. You can also try to find a bootleg DVD-R of it through various outlets (European Trash Cinema has an acceptable print) but Demons is a film that deserves a full restoration on Blu-Ray.

Two victims of a samurai warrior who was duped in an elaborate money scheme in Demons (aka Shura aka Pandemonium, 1971).

Other web links of interest:

https://www.fandor.com/posts/toshio-matsumoto-1932-2017

http://www.weirdwildrealm.com/f-shura.html

https://makeminecriterion.wordpress.com/2019/03/07/shura-toshio-matsumoto-1971/

http://lonewolvesandhiddendragons.blogspot.com/2011/03/shura-1971-review.html