Imagine a tunnel under the Atlantic that connected the United States with Europe and provided a high speed form of transportation between the two points. It’s certainly not an unrealistic expectation for the near future when you consider that the undersea rail known as the Channel Tunnel (aka the Chunnel) that currently connects Folkestone, Kent in England to Coquelles, France has been in operation since 1994. But that remarkable feat of engineering is only 50.5 km. compared to the 5,000 km. that would be the more likely distance of an undersea rail that connected New York City with London. Still, proposed plans for under-the-sea travel connectors between countries separated by water continue to surface in news reports and may happen in the near future. What’s most remarkable is the fact that Transatlantic Tunnel (aka The Tunnel), a 1935 British film, envisioned the same thing and some of that movie’s futuristic art direction and design is not that far removed from some of the models you can view on the interest today (just do a search for undersea rail systems).

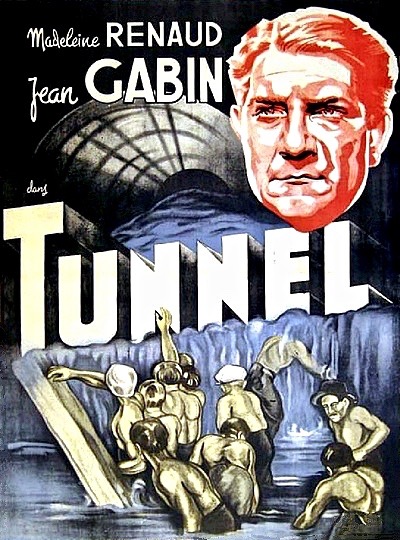

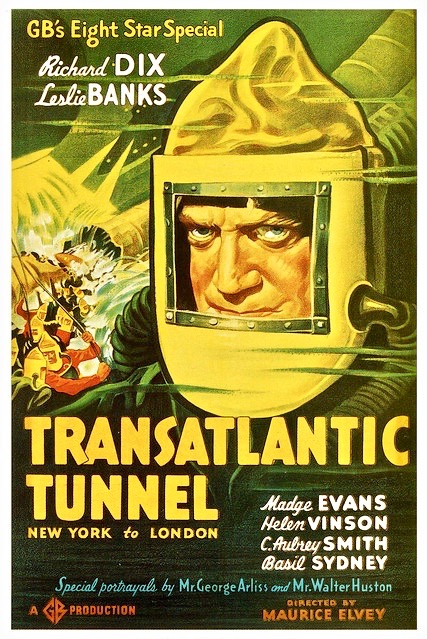

Set in some distant future beyond 1940, Transatlantic Tunnel is a fascinating, rarely screened science fiction fantasy that is a remake of both the German silent, Der Tunnel (1915), and a 1933 French version starring Jean Gabin entitled Le Tunnel, directed by Curtis Bernhardt. I’ve not seen those versions but the 1935 Gaumont British release that stars Richard Dix is a curious blend of utopian fantasy, soap opera, tragedy and disaster movie, all rolled into one.

The film’s mixture of British and American actors and the central plot of physically forging a connection between the U.S. and Great Britain is also evocative of a time when the two nations were much more demonstrative about a League of Nations-like brotherhood. George Arliss, that renowned star of the British stage and screen, even makes a cameo appearance as England’s prime minister (a character obviously modeled on his Oscar-winning role as Disraeli), proclaiming that the tunnel will be “an artery through which will course the life-blood of our two nations, flowing into the hearts of Anglo-American relations.” Supporting this idealistic venture 100 percent is the President of the United States, played by Walter Huston (also in a cameo role).

[Spoiler Alert] The real drama and interest is generated by the central premise in which Richard Dix’s engineer hero, Richard McAllan, solicits international financing for his dream project and after getting the green light, risks his life and the lives of thousands of men, to accomplish the daunting task which takes a heavy toll on most of those who commit themselves to it. McAllan, however, is the type of driven, single-minded visionary that could truly be accused of “tunnel vision.” He puts his job before everything else in his life, including his wife, son, lifelong friends and even his own personal safety. As a result, his marriage falls apart and his wife Ruth (Madge Evans) loses her eyesight while volunteering as a nurse in the tunnel’s medical facilities; workers exposed to deadly gases in the tunnel transmit their toxic effect like a virus.

Richard McAllan (Richard Dix) addresses his tunnel workers on a TV monitor in the 1935 sci-fi drama, Transatlantic Tunnel, directed by Maurice Elvey.

Even worse, McAllan’s son Geoffrey (Jimmy Hanley), who is like a stranger to McAllan after spending most of his young life in boarding schools, becomes a casualty the first day he volunteers to help his father on the job. He is trapped and suffocated with hundreds of others in a horrible drilling accident involving an underwater volcano. The grim events continue with a bitter falling out between McAllan and his best friend and co-worker Robbie (Leslie Banks) over McAllan’s wife.

Richard McAllan (Richard Dix, center) has a disagreement with his friend Frederick Robbins (Leslie Banks) while socialite Varlia Lloyd (Helen Vinson) looks on in Transatlantic Tunnel (1935).

On top of this, Varlia (Helen Vinson), the beautiful, wealthy daughter of the project’s main millionaire investor (C. Aubrey Smith), is trying to steal McAllan away from his blind wife while some of the treacherous investors double cross each other for sole ownership; one even kills his business partner with a poisoned cigarette.

Helen Vinson plays “the other woman” in Richard Dix’s busy life in the sci-fi drama Transatlantic Tunnel (1935).

Sure, it’s excessive and occasionally laughable in the way it stacks the deck with one melodramatic incident after another. Admittedly, the soap opera aspects tend to stall the suspense and excitement built up in the spectacular tunnel segments. Yet, despite occasional pacing problems, Transatlantic Tunnel is surprisingly visionary at times.

An example of the futuristic set design in the 1935 sci-fi drama, Transatlantic Tunnel, directed by Maurice Elvey.

The opening sequence of the film is particularly striking with the camera pulling back from the conductor of a live orchestra to reveal that the musicians are not performing in a theater but in the living room of a millionaire’s mansion. Then we see the bored faces of the gathered guests – selected crown heads of international industry. One leans over to his wife and says, “Will this tune ever end?” “It’s Beethoven,” she replies, pausing one beat and then, “He’s dead.” “Good!” is his response. With a simple click of a switch the orchestra is soon hidden from view and silenced by the millionaire host who turns his attention to the matter at hand, a plea for money for a project that will benefit mankind.

An upper class gathering discuss investment opportunities in new technology in the sci-fi drama Transatlantic Tunnel (1935), directed by Maurice Elvey.

Of course, this crowd is only interested in profit margins and the film’s depiction of these potential investors is quite telling. They have no interest in culture – that was apparent in their bored response to a Beethoven symphony. And they have no shame in expressing their nihilistic worldview or class-conscious contempt for anyone not in their inner circle. One jaded guest comments snidely to Varlia on the visiting American’s project and personal character – “They’re such dull things – tunnels. Don’t try to analyze him my dear. He’s a kind of human mole. It’s all right if he’s underground but blast if he comes up in daylight! Besides, look at his clothes.”

While McAllan’s proposal is at first rejected, the businessmen are eventually talked into investing by their host who appeals to their simple greed. The munitions millionaire says with supreme confidence, “When your tunnel is built, all the other countries of the world will come to me for guns to blow it up.” We could just as well be witnessing a private meeting of Halliburton executives discussing how they are going to get even richer off the Iraq War.

Some of the futuristic design on display in Transatlantic Tunnel will bring a smile to your face such as the tunnel rail cars which look like something out of The Jetsons. But some of it looks forward to genuine technological advances such as the ‘televisor’ – a combination video screen/phone – or the ‘enunciator’ – an early form of wireless loudspeaker. And the large wall size TV monitors installed in people’s homes where you can enjoy face to face communication with the other party pre-date Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451 as well as other technologies developed in recent years.

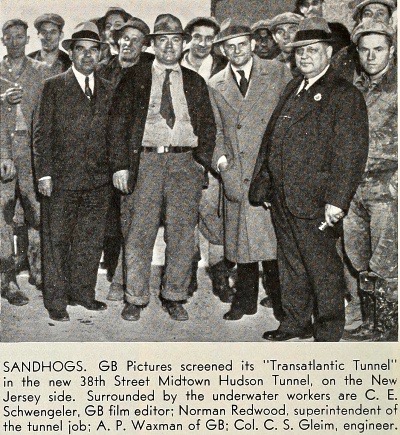

The most striking set design though is the actual tunnel set with its massive high ceilings and endless rail retreating into the distance. The huge radium drill is equally spectacular and so are the disaster sequences with masses of workers fleeing through fiery, smoke filled chambers and McAllan in his deep sea diver-like protective gear rushing to the rescue (Allegedly some of the special effects shots from the German and French versions of The Tunnel were rumored to have been reused in this film).

Which reminds me…there is some unavoidable and hilariously phallic exchanges in the film such as McAllan’s excited live broadcast to the public: “Down here, far below the Atlantic bed, strewn with the wrecks of centuries, men are working day and night from both sides of the Atlantic. They are driving their shafts nearer and nearer to one another. And one day far below the raging storms of the ocean they’ll meet and the greatest engineering dream the world has ever known will become an accomplished fact.”

Underground workers in the sci-fi drama Transatlantic Tunnel put their lives on the line and sometimes pay the cost.

There’s also a funny homoerotic male shower sequence that rivals the female one in Gold Diggers of 1933 with half-naked men splashing each other with water and telling jokes against a frosted glass background where we see the silhouettes of other men bathers.

If there is a lesson to be learned from Transatlantic Tunnel it is that ambitious projects that serve mankind like the Tunnel demand a sacrifice that men like Richard McAllan are willing to make. What’s more important, devoting your life to a humanitarian project or being a successful father and husband? Is it possible to do both? Not likely. When McAllan is asked at the end of the film if he would do it all again knowing the heavy price he would pay, he says yes because, “I believe my work will bring peace to the world.” Men like McAllan are essential in the progress of the human race – but good luck to their wives and children!

When one considers other British science fiction films from the same era, Transatlantic Tunnel easily stands out as one of the best. It was released the year before two H.G. Wells film adaptations, Things to Come (based on the H.G. Wells novel The Shape of Things to Come) and The Man Who Could Work Miracles, and holds up much better than either of those films, despite the stunning art direction of the former and enjoyable whimsy of the latter.

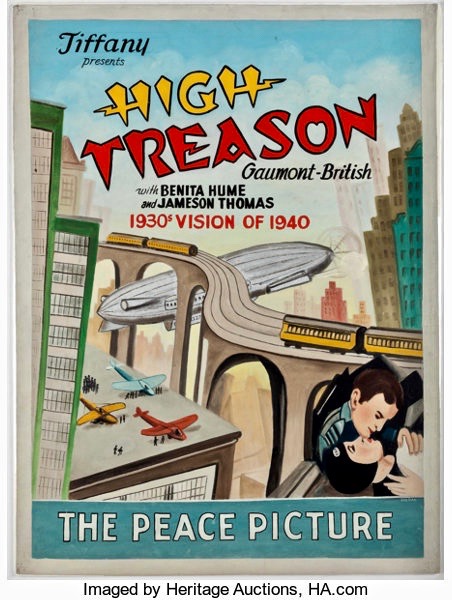

Maurice Elvey, director of Transatlantic Tunnel, had previously helmed another film entitled High Treason (1929) in which a tunnel linking England to Europe was a subplot. It was Gaumont’s first official “talkie” but was also released as a silent. Elvey would go on to direct The Clairvoyant aka The Evil Mind (1935) starring Claude Rains, but most of his films were not in the fantasy genre.

Transatlantic Tunnel was previously available on VHS and is available on DVD in various editions but the quality will be variable since the film is in public domain. A poor quality copy of it can also be streamed on YouTube. If the original film elements could be located for a restoration, a Blu-Ray would certainly be more than welcome but the chances of this happening seem slim to none.

Other websites of interest:

https://immortalephemera.com/52708/richard-dix-biography/

https://www.eetimes.com/author.asp?section_id=69&doc_id=1286366#

https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucedorminey/2016/04/29/the-case-for-transatlantic-undersea-trains/

http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/449112/index.html

http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/93824/Transatlantic-Tunnel/articles.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YFjJUcfyKqs