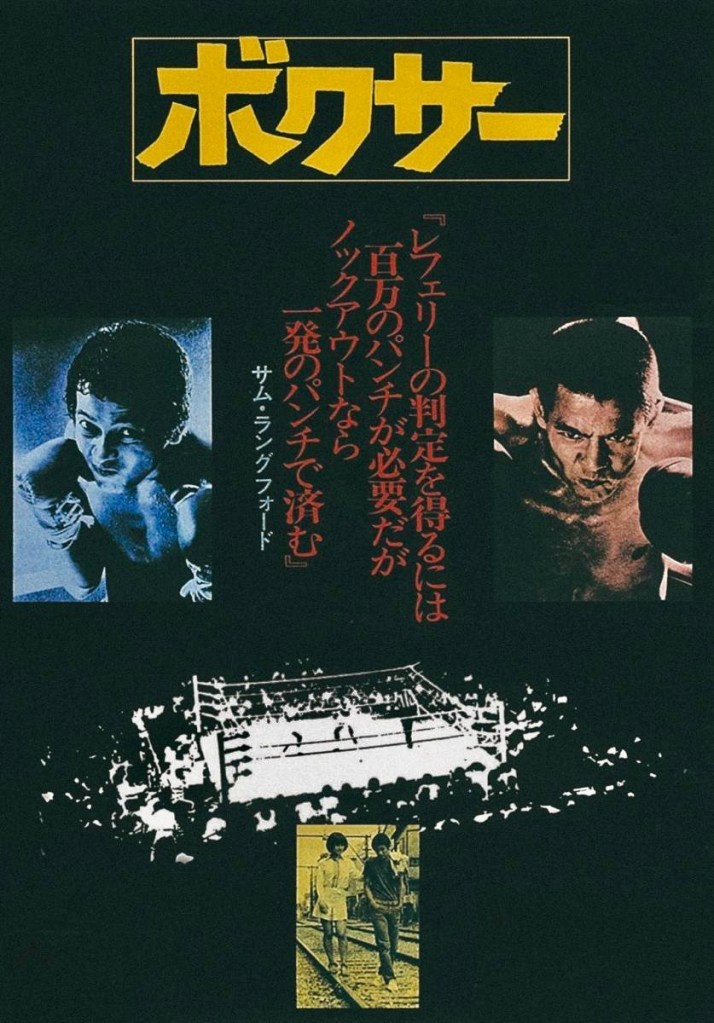

Movies about boxers often seem to break down into four categories; the most popular are the ones where the underdog fighter overcomes all odds to become a champion (Rocky [1976], Million Dollar Baby [2004], Cinderella Man [2005]). Then there are true-life biopics like Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), Raging Bull (1980) and Ali (2001), downbeat character portraits of boxers past their prime (Requiem for a Heavyweight [1962], Fat City [1972]) and noir dramas that highlight the corrupt aspects of the profession like The Set-Up (1949) or The Harder They Fall (1956). Bokusa (English title: The Boxer (1977), a Japanese film directed by Shuji Terayama, has elements of some of the above but it is decidedly different from any American film in the boxing genre.

You can tell from the first ten minutes of The Boxer that the director is merely using the basic outline of an underdog fighter training for a comeback to experiment with color and black and white cinematography, unusual camera angles, lighting, editing, offbeat narrative details and a wildly eclectic music score (by J.A. Seazer) to create something poetic and immersive about the world in which the main characters struggle to survive. In Terayama’s portrait, the boxing world is less important that man’s desire to either self-destruct or challenge himself and sometimes the most heroic thing you can do is simply endure instead of giving up and fading away.

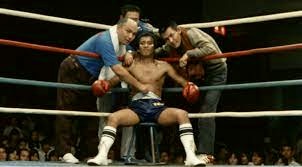

The storyline of The Boxer focuses on Hayato (Bunta Sugawara), an ex-boxer who abruptly left the profession in the middle of a bout. The reasons for his decision are never made clear but he does acknowledge the fact that most of the great boxers he admired are either dead or died tragically which didn’t bode well for his own future. He now supports himself by posting boxing flyers on walls around the city and lives in a shabby boarding house with his dog in a poor neighborhood. Hayato’s retreat from the world also involved abandoning his wife (Masumi Harukawa), who remarried, and his daughter Mizue, but he is jolted out of his aimless existence when his brother is killed in a work accident.

Enter Tenma (Kentaro Shimizu), a struggling boxer with a bum leg who works at a scrap metal junkyard where he operates a crane. When he drops a wrecked vehicle on a co-worker (Hayato’s brother), is it an accident or murder? The two had been feuding over a woman who ended up rejecting Tenma. Hayato is outraged at the news and confronts Tenma at his boxing club where he is forced out by the other boxers. But in a strange turn of events, Tenma ends up begging Hayato for forgiveness and asks him to be his personal trainer.

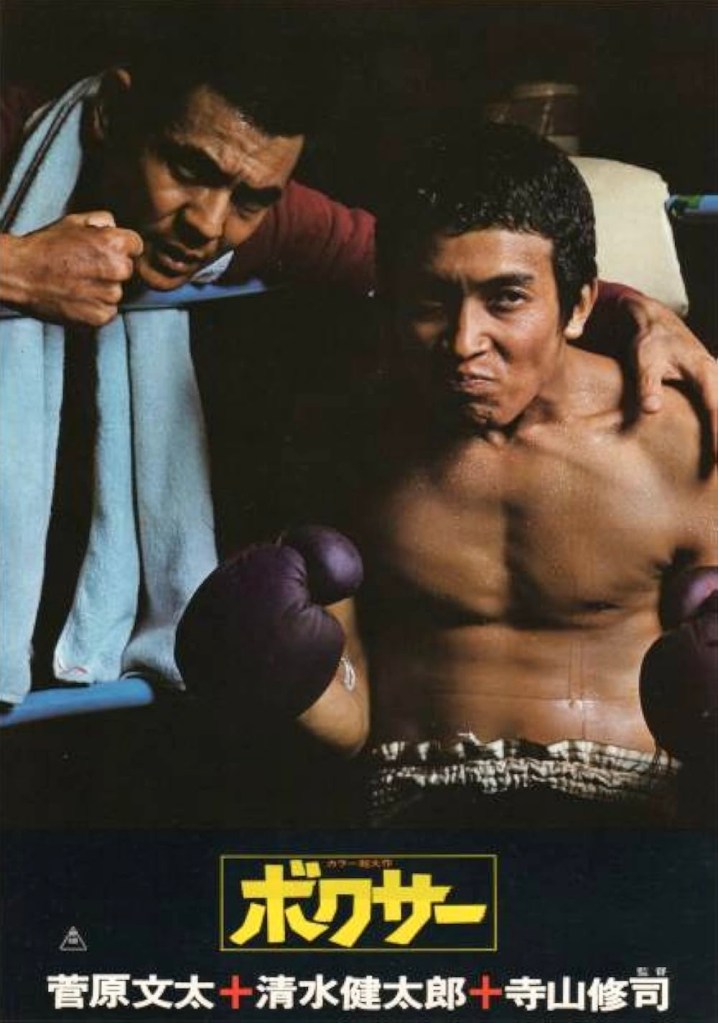

Hayato is antagonistic at first but sees something of himself in the scrappy but determined pugilist. He soon subjects Tenma to a series of punishing exercises to improve his performance in the ring while also encouraging him to use hate as a motivator. Tenma buys into the nihilist attitude and says he hates his parents, his siblings, and, as an afterthought, adds “Damn, I hate the whole world!”

The second half of The Boxer depicts Tenma and Hayato’s evolving relationship which goes from combative to mutual respect but never becomes sentimental unlike the Sylvester Stallone-Burgess Meredith fighter/trainer partnership in Rocky. As the film approaches the championship fight that could make or break Hayato’s comeback, however, director Terayama intentionally downplays the mounting dramatic tension, opting instead to spend time on Hayato’s relationship with his ex-wife and daughter and the losers and dreamers who hang out a local café where Tenma has his own fan club.

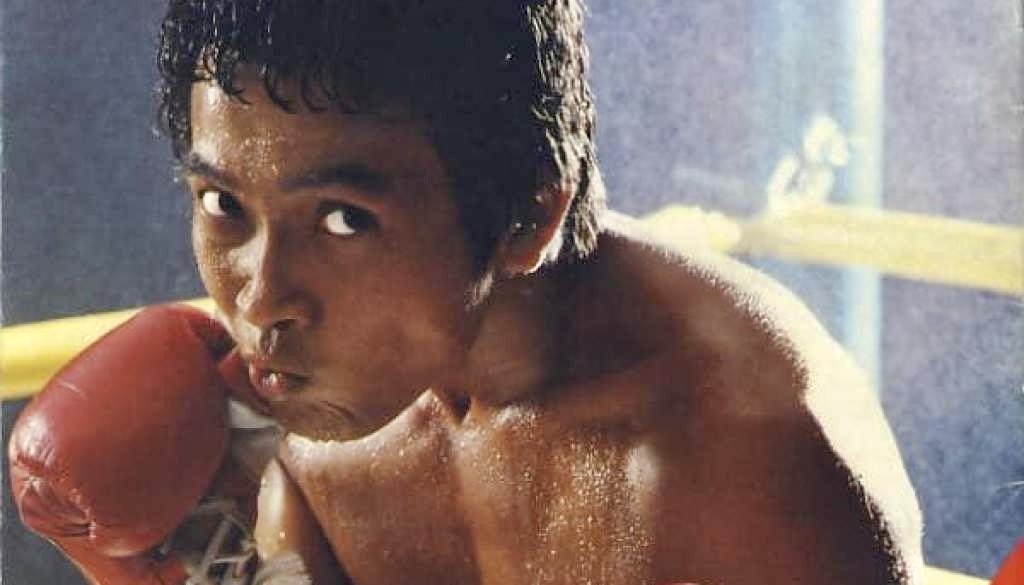

At times The Boxer looks and feels like an experimental film with its stylistic treatment of certain plot devices like a flashback to depict Hayato’s past (a brutal fight unfolds like a red-tinted nightmare). Instead of wide shots, the viewer is often subjected to intense close-ups of fists pummeling sweaty torsos which are mixed with cutaways to a boxer’s fancy footwork on the canvas floor. It is both disorienting and surrealistic and a balletic display of the physical movements that make boxing an endurance test for the human body.

An oddball sense of humor also emerges occasionally such as a scene where live chickens escape the cafe’s kitchen and create chaos in the serving room as patrons try to corral the runaway birds. Another brief sequence depicts Hayato’s dog, drunk on beer, running along the railroad tracks into the distance, never to reappear.

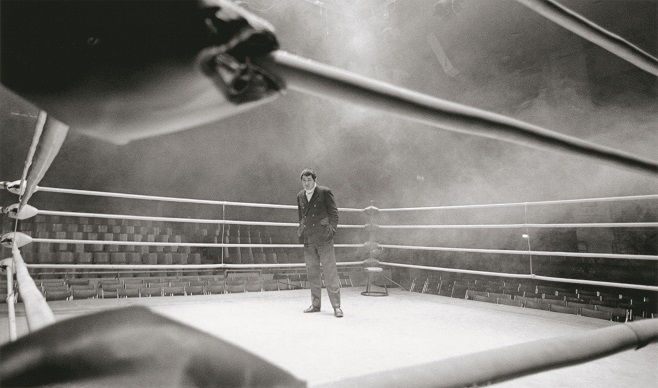

Probably the most inventive and subversive scene in The Boxer occurs during the championship fight. Tenma and his opponent have both collapsed on the floor of the ring and the referee is counting down to a double knockout unless one of them can stand up in time. Terayama decides to shoot this dramatic moment from Hayato’s point of view, who at this point in the story is losing his eyesight. What we end up seeing is a color muted, soft focus view of the ring where the human forms inside it are little more than indiscernible blobs. The only way Hayato realizes Tenma has won the fight is because he can hear the boxer’s fans cheering his victory. This would never be allowed in a Hollywood production but in Terayama’s film it becomes one more reason why The Boxer is in a category of its own – part art film, part genre exercise. And the movie is accessible enough to serve as a gateway film into Terayama’s filmography.

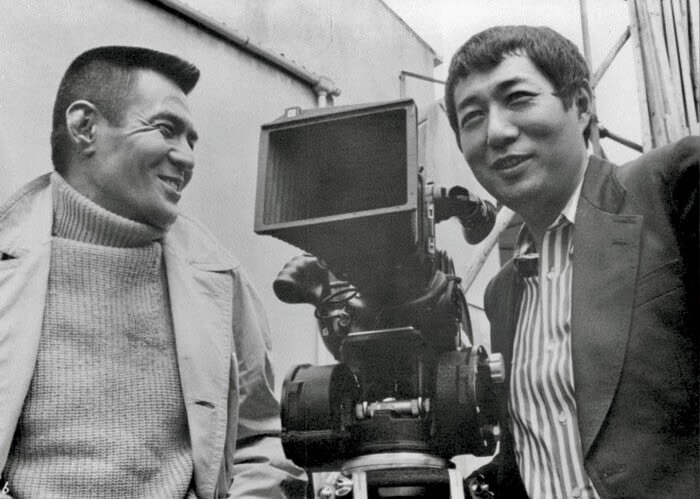

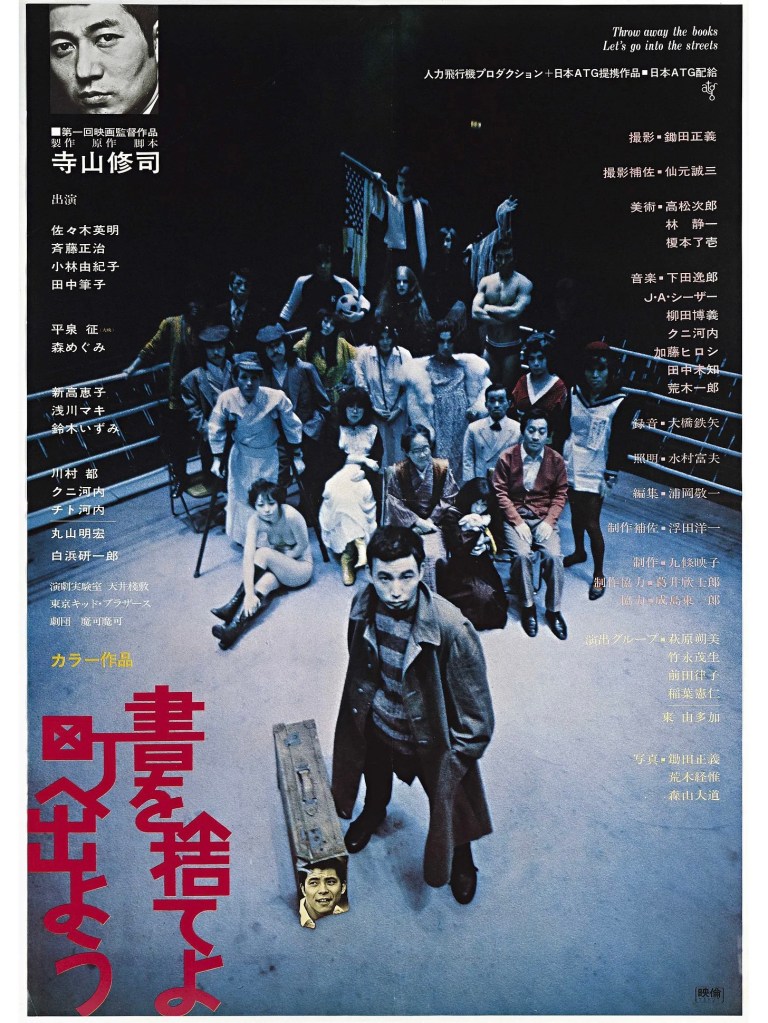

It is also Terayama’s rare collaboration with a major Japanese studio, Toei, and, as such he had to concede to certain commercial demands but still managed to invest The Boxer with his own sense of aesthetics and visual approach. The director’s other film work is decidedly avant-garde starting with his debut feature, Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets (1971), a radical attack on Japanese consumerism with a rebellious teenager and his dysfunctional family at the center of the story. Fueled by a soundtrack of Japanese garage rock, the film is an assault on the senses with its unconventional switching between black and white and color stock and different formats such as 35mm, 16mm and super-8. Terayama’s follow-up feature Emperor Tomato Ketchup (1971) is even more extreme and features a dystopian world of the future in which children, armed with guns and paint, create chaos. Alternating between the playful and the offensive (simulated sex between adults and children), the film was censored upon its release and banned in several country yet it seems like the work of an underground maverick like Jack Smith (Flaming Creatures, 1963). His third feature, Pastoral: To Die in the Country (1974) is a semi-autobiographical, coming of age story which has been compared to the work of Alejandro Jordorowsky (El Topo, 1970) and Fellini, especially the scenes featuring a traveling circus.

Terayama would go on to produce several other film shorts and features including The Boxer and Fruits of Passion (1981), a semi-pornographic tale starring Klaus Kinski, which is set in a brothel and based on a book by Dominique Aury, the anonymous author of The Story of O. But Pastoral: To Die in the Country and Farewell to the Ark (1984) are generally considered his two most critically acclaimed films and established his reputation on an international level (Both films were nominees for the Palme d’Or award at Cannes). What is most interesting about all of this is that filmmaking was not what made Terayama famous in Japan. He was a true renaissance man who worked as a poet, photographer, essayist, theater manager and playwright, and sports writer (he loved boxing and horse racing), among other interests. But it was his poetry, which he began writing in high school, that first attracted national attention and raised his profile in Japan. He also gained notoriety for his controversial advice to young people of his generation – break away from domineering mothers and flee all oppressive families to become your own person. Unfortunately, Terayama died young (at age 47 from liver failure) but his reputation as Japan’s most famous post-war counter-culture artist remains undiminished.

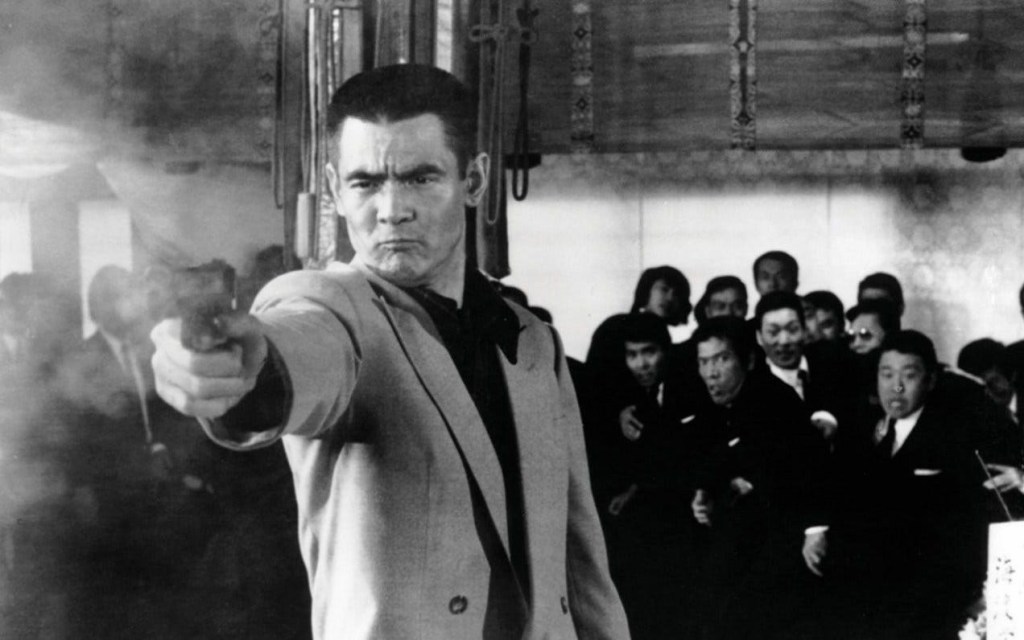

The Boxer remains a fascinating example of Terayama working within the strictures of the studio system but is also of interest to Japanese cinema fans for its casting. In the lead role of Hayato, Bunta Sugawara is completely convincing as an apathetic, burnt-out case who becomes re-engaged with life after losing his brother. At this point, Sugawara was best known for his roles as raging yakuza types in crime thrillers, many of which were directed by Kinji Fukasaku such as Street Mobster (1972), Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973), Proxy War (1973), and Cops vs. Thugs (1975). The Boxer, however, showcases Sugawara in a decidedly different milieu with a more introspective and sympathetic portrayal.

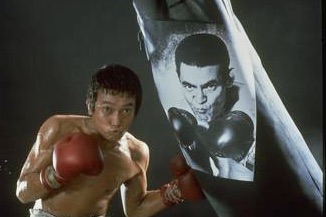

Kentaro Shimizu is also effective in his role as Tenma, displaying an unpredictable mixture of vulnerability and cockiness, such as the scene where he tells his trainer, “I want to be a champion, be seen on TV. I want to make a fortune, to surprise everyone.” But there is also a sense of self-loathing beneath it all, which is obvious in the sequence where he pastes his own self-portrait on his punching bag and decimates the image with his furious punches. Shimizu had a modest career as an actor, making less than forty feature films (he has been inactive since 2004), but he is quite memorable as a villain in the over-the-top female revenge thriller Mermaid Legend (1984).

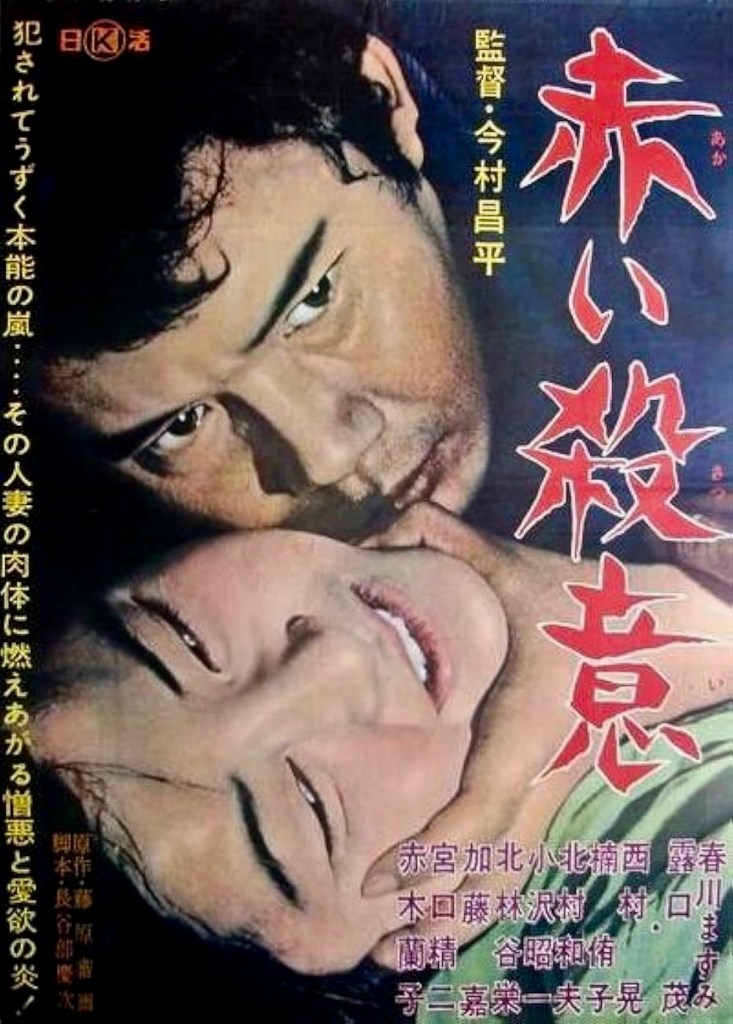

Another familiar face in The Boxer is Masumi Harukawa as the ex-wife of Hayato. Her versatility as an actress is on display in such iconic Japanese films of the 60s & 70s as The Insect Woman (1963) and Intentions of Murder (1964) – both directed by Shohei Imamura, the delightful black comedy The Glamorous Ghost (1964), the supernatural thriller House of Horrors (1965), Kinji Fukasaku’s The Threat (1966), and Terayama’s Pastoral: To Die in the Country (1974).

Among the few reviews of The Boxer that I have found, the majority have recommended the film. Josh Slater-Williams of the BFI stated that the film “is still among the most surreally visualised boxing films ever made, where fused rainbow colours seem to constantly bleed from the sky. You have the more standard training montages and thwarted dreams, but Terayama’s greater focus is on the punishment and dedication of the body in combat: on what someone can and can’t achieve when pushed to physical limits.” And Scott Meek of Time Out wrote “Terayama has here brilliantly fused the elements of his previous film and theatre work – surrealism, a sense of the essential anarchy of relationships, and a flair for startling and beautiful images – with a compulsively exciting Hollywood-style narrative about a young man’s relentless ambition to be a champion boxer. The film synthesises these seemingly disparate approaches while allowing them separate existences, and through this evokes not only a poetic vision of modern industrial Tokyo and the fading dreams of the city’s losers, but also a tense and realistic portrayal of the sheer brutality of the world of boxing, in its inexorable attraction and its heroic despair.”

The problem facing U.S. cinephiles who are interested in exploring the director’s work is lack of access to his filmography. He is practically unknown here since few, if any, of his movies have ever received theatrical distribution in America. And so far no Blu-ray/DVD distributors show any signs of acquiring and restoring his work such as Radiance Films, Vinegar Syndrome or other cult labels. The good news is that you can currently stream The Boxer in a serviceable print with English subtitles on Youtube (although it could be removed tomorrow so act now!).

Other links of interest:

https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/where-mountain-meets-street-terayama-shuji

https://www.coeval-magazine.com/coeval/shuji-terayama

https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/sleek-guide-shuji-terayama-films/

https://harvardfilmarchive.org/programs/shuji-terayama-emperor-of-the-underground