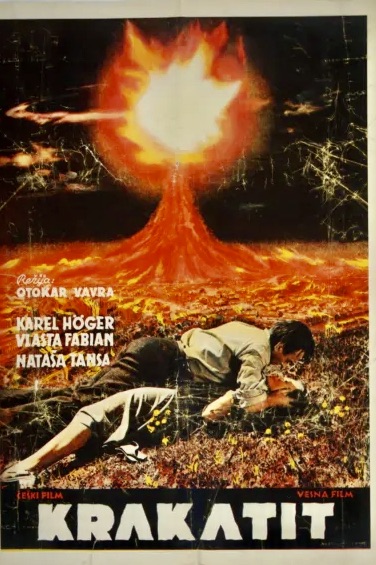

Why would a scientist create a weapon of mass destruction that was capable of destroying the planet and ending life as we know it? J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist who led the Manhattan project and is known as the “father of the atomic bomb,” would later become guilt-ridden over his invention but his original intention was altogether different. He wanted to create a weapon so powerful and dangerous that it would intimidate all world leaders into putting an end to war but, of course, that idealistic concept ended in failure because human beings are flawed creatures. This same scenario is mirrored in the Czech sci-fi drama, Krakatit (1948), in which an engineer named Prokop (Karel Hoger) creates a powder that can become explosive and release atomic energy when activated by radio signals or other means. Like Oppenheimer, Prokop quickly comes to regret his discovery but a case of amnesia caused by an accidental explosion complicates the engineer’s desperate search for an associate, Jiri Tomes (Miroslav Homola), who stole the formula.

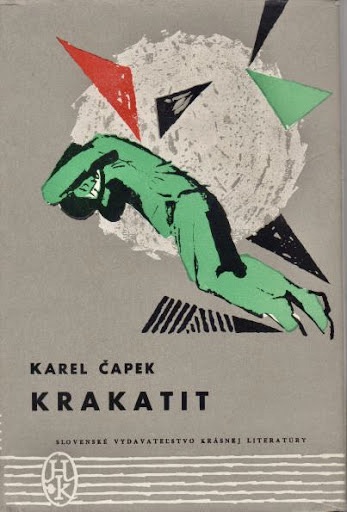

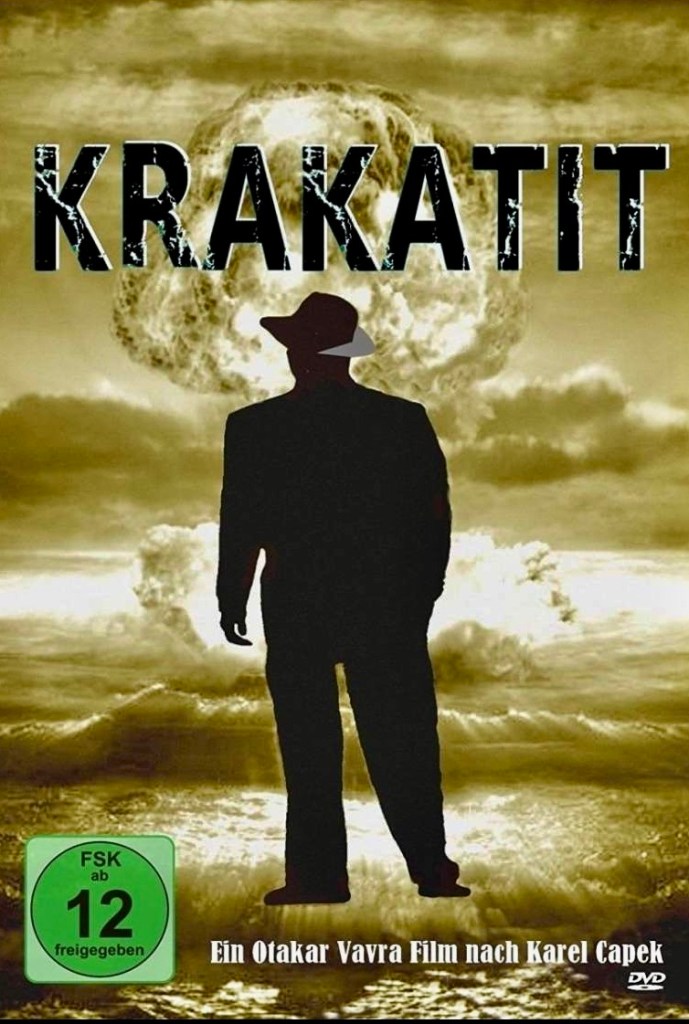

Krakatit, which was made between WW2 and the Cold War, was a timely reflection of its era when fears of a nuclear war were pervasive. What is surprising is that Krakatit was based on a novel by Karel Capek, which was written in 1922, just four years after WW1. The novel was so prophetic that it was even more relevant in 1948, more than 25 years later. (Capek’s original title was inspired by the 1883 volcanic eruption of Krakatoa in the Dutch East Indies and its destructive effects.) Thanks to Czech director Otakar Vavra, Capek’s tale was transformed into a stylish blend of allegory and grim fairy tale, which was filmed in the style of a film noir mystery.

The movie, which opens in a hospital room where Prokop is being treated for a high fever and chemical burns, is told in flashback as the protagonist drifts in and out of his temporary amnesia. We learn that Prokop is consumed with anxiety over his discovery and most of the film depicts his attempts to prevent the formula from falling into the wrong hands. His journey takes him from a brief idyllic stay with Jiri’s father, Dr. Tomes (Frantisek Smolik), and Anci (Natasa Tanska), Jiri’s sister, to a more sinister situation where he finds himself imprisoned by some power hungry aristocrats and military figures and ordered to create the explosive material for their purposes. Even though he rebels against his predicament, Prokop is temporarily distracted by his attraction to the seductive and beautiful Princess Wilhelmina (Florence Marly), who has her own secret agenda. She also appears to be sexually aroused by Krakatit’s lethal explosive qualities

[Spoiler alert] Krakatit builds to a literally explosive climax as a demonic entity known as Daimon (Jiri Plachy) tricks Prokop into igniting his creation around the globe (it has been spread everywhere by airplanes) and the engineer witnesses its lethal power but does the world come to an end? Much of Vavra’s film unfolds like a series of fever dreams in the mind of Prokop and the viewer has to determine what is real and what is fantasy. Yet, despite the doomsday tone, Krakatit ends on a positive note as our protagonist vows to only make scientific discoveries that aid mankind, not threaten it. This still doesn’t explain why a scientist would create a deadly pandora’s box and then forbid anyone to open it. That sort of contradiction is what drives the narrative of Krakatit and helps explain the main’s character’s tormented state of mind.

Some sources claim Krakatit was Czechoslavakia’s first film entry at the Cannes Film Festival and director Otakar Vavra would go on to remake the film in color in 1980 under the title Temne Slunce. Capek’s novel would also be adapted for two made-for-TV movies on Czech TV, one in 1961 and one in 2017. The film was generally well received by most European film critics but garnered mixed reviews in America where The New York Times called it “a strident preachment for peace and against destructive nuclear fission” and Variety, which observed that “Most of the villains (and the film is loaded with them) look like Germans, and many of the top connivers either are of the elite or royalty in the mythical land depicted. And in some of the attempts at propaganda against the bomb, the story becomes confusing.”

Barely seen in the U.S. since its initial premiere in 1951, Krakatit is rarely cited by sci-fi fans in discussions of apocalyptic fantasies such as Things to Come (1936), Five (1951), The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959) and On the Beach (1959), due to its relative obscurity. Yet, it is still considered a sci-fi classic in Eastern European cinema and deserves a revival despite some obvious shortcomings. For one thing, Krakatit is excessively verbose, the pacing is often slow and the flashback structure can be confusing but there are some major compensations. The black and white cinematography by Vaclav Hanus is truly stunning and creates a fantasy world of fog, shadows and brief moments of natural beauty (Prokop gathering a bouquet of water lily blooms for Anci, the lush landscape of the Wilhelmina estate). Tilted angles in the hospital scenes and a drunken nightclub outing where Prokop experiences triple vision also add to the dreamlike visual design.

The art direction by Jan Zazvorka effectively conveys a sense of the fantastic in ways that rival the legendary William Cameron Menzies’s work on Things to Come, The Thief of Bagdad (1940) and Invaders from Mars (1953) such as the scene where Prokop first views Jiri Tomes’s elaborate research laboratory across a barren, checkered plain or the surreal flashback sequence with Prokop at the university in an enormous lecture hall where the students are rendered as cardboard cutouts in the background.

Just as distinctive is the dissonant music score by Jiri Srnka which utilizes unusual instruments like the Theremin and converts natural sounds like wild bird cries into mechanical sound effects. All of these would be enough to make the film memorable but the performances, especially by Karel Hoger in the lead role and Florence Marly as the Mata Hari-like Wilhelmina, help separate Krakatit from typical sci-fi genre fare and stand out as thought-provoking art house cinema.

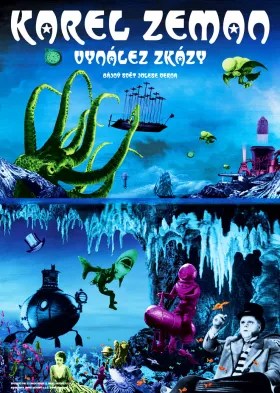

Hoger, who began his career as a teacher and ended up as a stage actor with the prestigious Prague National Theatre, made more than 100 films and TV shows during his more than 36 year career. American viewers might recognize him from his role as Cyrano de Bergerac in Karel Zeman’s outlandish fantasy, The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1962).

Marly, on the other hand, had a much more unusual career as a Czech-born actress. She got her start in French cinema appearing in such films as Pierre Chenal’s crime drama The Lafarge Case (1938) and Rene Clement’s war thriller Les Maudits aka The Damned (1947). Her leading role in Krakatit introduced her to international audiences and Hollywood quickly came calling, importing her as a mysterious Greta Garbo-like beauty for movies like Sealed Verdict (1948), her U.S. debut, and Tokyo Joe (1949) opposite Humphrey Bogart. Unfortunately, she never made much of an impact in American films but she did find occasional work in guest appearances on TV series like Dragnet, The Twilight Zone and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. It wasn’t until much later in life that Marly achieved cult status for her eerie but unforgettable presence in horror offerings such as Curtis Harrington’s Queen of Blood (1966) and Games (1967).

One reason Marly’s U.S. career never flowered is probably due to the fact that she was unfairly blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee, who got her confused with the Russian born singer Anna Marly. As a result, Hollywood moguls like Jack L. Warner of Warner Brothers refused to hire her.

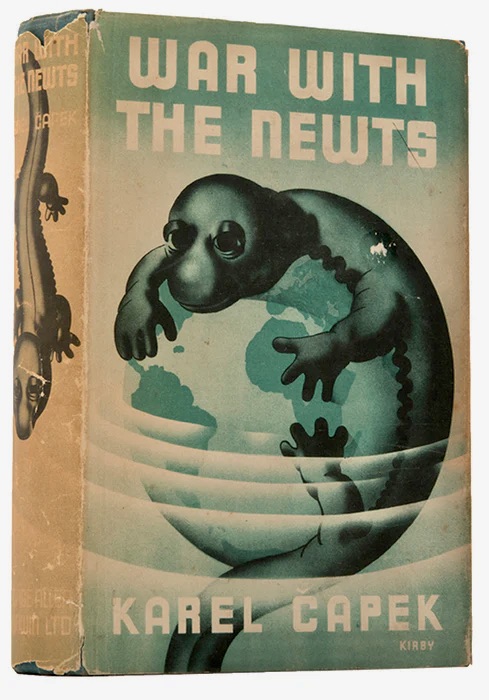

One thing viewers will notice about Krakatit is that in addition to the film being an anti-war allegory, it is also a cautionary fable about fascism and dictatorships. This is no surprise since Karel Capek, author of the original novel, was a witness to the suppression of democracy during his own lifetime with the Fascists’ coup in Spain in 1923 and the rise of communism in Russia. Look closely for the scene in the movie where Wilhelmina’s political allies at a private rally include a rabble-rousing pro-war speaker who looks and acts like a double for Hitler. Capek’s views were certainly noticed by the Nazi party and he was marked for certain death by the Gestapo but he died in 1938 before his enemies could capture and execute him. He is still recognized today as one of Czechoslovakia’s most gifted writers and a true science fiction visionary whose work impressed H.G. Welles and other masters of the form. Among his more famous novels are R.U.R. (1921), which first introduced the word “robot,” The Makropulos Affair (1922), a play about prolonging life through unnatural means, The Absolute at Large (1922), a satire about an invention that can produce cheap energy but comes with a destructive side effect, and War with the Newts (1936), in which a breed of highly intelligent salamanders (they can speak, read and write!) are exploited by humans.

One last comment on Krakatit concerns the director, Otakar Vavra, who taught at Prague’s renowned FAMU and is considered “the father of Czech cinema,” based on the landmark films he directed in the 1950s and 60s, including his Hussite trilogy (Jan Hus, Jan Zizka aka The Hussites, and Proti Vsem aka Against All Odds, 1954-1957), Zlata Reneta (1965), in which an elderly librarian discovers “you can’t go home again,” and Witchhammer (1970), a disturbing historical drama about the persecution of innocent people during the 1600s, especially women. As a member of the Communist party, Vavra was supportive of the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslavakia in 1968 and was allowed to continue to make films under their regime as long as he followed the party line. Still, none of his later work matched the artistic virtuosity of his sixties films with the possible exception of Dny Zrady (1973), a historical epic about the futile efforts of Czech president Edvard Benes to prevent the Nazi invasion of his country.

For those who are interested, Krakatit is available in different import DVD/Blu-ray editions from online sellers but you would need an all-region player to view them. This seems like the sort of title that might get the prestige film restoration treatment from The Criterion Collection or an indie outfit like Deaf Crocodile. That might never happen so, in the meantime, you can stream a beautiful print of Krakatit on Youtube. There are no English subtitles unfortunately but you can still follow most of the storyline on a purely visual level. (The restoration was sponsored by the National Film Archive in Prague in 2016 with the assistance of the Hungarian Filmlab in Budapest).

Other links of interest:

https://www.historytools.org/people/karel-capek-complete-biography

https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/capek-karel

Great review!