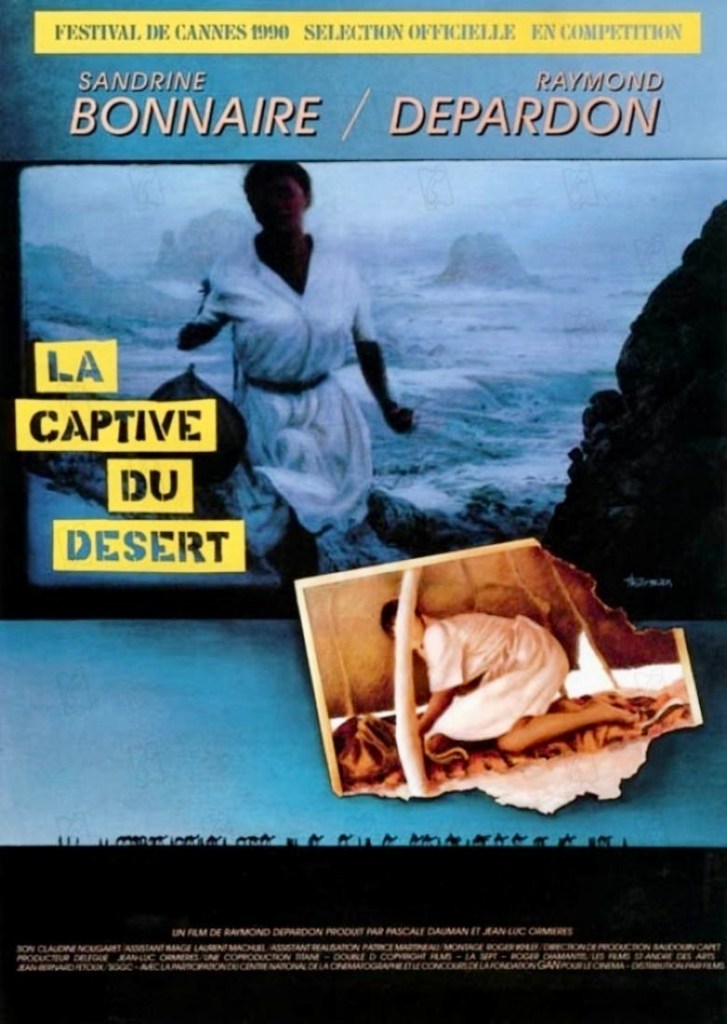

In the Spring of 1974, French archeologist Francoise Claustre along with a young aide and a German doctor and his wife were captured by rebel forces in Chad, Africa while exploring pre-Islamic tombs. The doctor’s wife was killed during the attack but her husband was quickly released after West German officials paid his ransom. The aide later escaped but Claustre remained a hostage of the Maoist rebel leader Hissene Habre and his clan for 33 months. During that time, her husband Pierre, a French official, tried to bargain with the rebels when his government proved inept at handling the situation but he too ended up being captured and held in a different camp in Chad. Renowned photojournalist and documentary filmmaker Raymond Depardon was allowed to interview Francoise during her ordeal for his non-fiction shorts, Tchad 2: L’ultimatum (1975) and Tchad 3 (1976), which were broadcast on French TV and provoked a major public outcry over the entire situation. Finally in January 1977 Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi brokered a deal with the Chad rebels and the French couple was released and returned to Paris. Interestingly enough, Depardon would return to this subject again in 1990 with La Captive du Desert (Captive of the Desert), a fictionalized account of the Claustre affair which remains one of his few forays into feature film making.

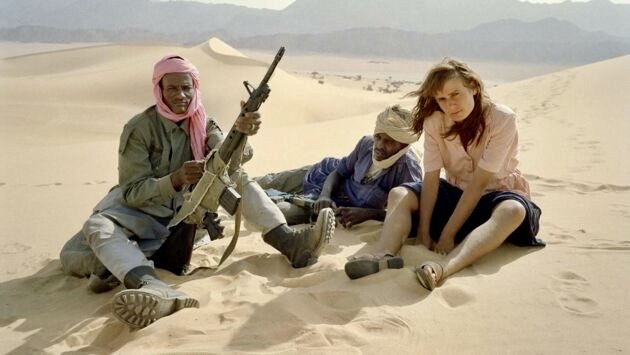

If you were to see Captive of the Desert without knowing anything about it in advance, you would have no context or understanding about what you were watching. Depardon drops the viewer into an extreme situation with no backstory in which the title character, who is never identified by name and is played by Sandrine Bonnaire, has already been captured by a nomadic tribe of African rebels (also unidentified) and is forced to march with them as they wander from place to place in the Chad desert, looking for food and water while hiding from their enemies.

Who is this woman and why is she their prisoner? The answer is never learned until the final moments of the film when a rebel leader informs the captive she is free to return to France but until then, she is at the mercy of her jailers and constantly in fear of her life. The captive is never mistreated cruelly or physically abused but the threat is always there, which gives Depardon’s film a constant underlying tension. But the director is not interested in creating a dramatic arc for his narrative, even though there are isolated moments of action here and there (Bonnaire’s character escapes from her captors during a musical ceremony but ends up getting lost in the desert until she is rescued by a young boy from the tribe).

Instead, Depardon is more interested in creating an immersive cinematic experience where the viewer is made to feel the same sense of ennui, anxiety, disorientation, loneliness and alienation experienced by the captive. Time becomes meaningless in her situation as days and nights blend into each other without any contact with the outside world. At one point she seems to realize she will never be rescued and burns all her personal belongings – photos, passport, etc. – in a small bonfire as if to erase her memory from the earth.

The only dialogue heard throughout Captive of the Desert is a few brief responses from the captive when she is being questioned by her captors but the conversations among the tribal people are not subtitled, which only amplifies the Bonnaire character’s complete disconnect from this group. There is a brief respite from her grim circumstances when the captive teaches some tribal women a French song and they laugh together but the sense of entrapment is as powerful as it is in other films that explore the same theme of isolation such as Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes (1964).

If I had to compare the style and tone of Depardon’s film to another filmmaker, I would say Captive of the Desert is closer to something like Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) with its minimalistic, repetitious nature which slowly reveals insights or subtle details about the character and story. And like Jeanne Dielman, the captive is someone who is trapped in a role she doesn’t want to play.

Admittedly, Captive of the Desert is recommended for adventurous film lovers but its slow, meditative approach rewards the viewer in the end, especially if you are lucky enough to see it in a theater with a big screen and first-rate sound system. There is no musical score (although there are some tribal singing sequences) but the sound design is one of the film’s most effective virtues. Camel cries, blowing wind, the sound of feet clomping across the desert sands, a gun shot in the distance, a guard playing a crude string instrumental, water flowing into a cup – all of these sounds conjure up a specific environment being experienced by the protagonist.

The cinematography, also by Depardon, is equally evocative like his photographs and conjure up the harsh beauty and punishing weather of a sun-baked landscape where nothing seems to grow or survive (the movie was filmed in the Chirfa, Djaba and Orida regions of Niger). Depardon would later comment on the making of Captive of the Desert in an interview with Artforum magazine. He worked with a crew of only ten people in making the film but for him, even that was excessive. “It’s true that I’m not interested in that kind of production,” he said, “but I’m glad to have done it. Having your own chair with your name written on the back and talking with the star—it was kind of romantic, like Cecil B. DeMille with his megaphone. So it’s something I wanted to do, and I don’t regret it, but I think it’s one of my worst films.”

Some viewers may agree but others will find it a fascinating experiment. The movie was even nominated for a Palme d’Oro at the Cannes Film Festival. It certainly presented acclaimed French actress Sandrine Bonnaire with one of her most challenging roles. She spent 3 and a half months in the desert filming the movie and Depardon refused to give her direction because he didn’t consider himself a film director. Nevertheless, she completely inhabits her character with a palpable sense of despair, fatigue, anxiety and passive/aggressive resistance. Overall, she still manages to project a steely inner core and only breaks down in tears at the end when she is told she is free.

Bonnaire has remained one of French cinema’s most compelling and adventurous actresses ever since her breakthrough role at age 16 as a sexually precocious schoolgirl in Maurice Pialat’s A Nos Amours (1983). Her wide range and attraction to edgy material is reflected in some of her most critically acclaimed work such as the apathetic drifter in Agnes Varda’s Vagabond (1985), the object of a man’s obsession in Monsieur Hire (1989), the visionary crusader of Jacques Rivette’s Joan the Maid (1994), a mentally unstable housekeeper in Claude Chabrol’s La Ceremonie (1995) and a Russian Revolution survivor in East/West (2000). It is no surprise that Bonnaire would welcome the challenge of appearing in a non-conventional, semi-ethnographic experiment like Captive in the Desert.

For cinephiles who would like to see a more representative example of Depardon’s work in the documentary field, 12 Days (2017), a portrait of French psychiatric patients, Journal de France (2012), which documents the director’s road trip across his country, and Modern Life (2008), about farmers in Southern France, are among his more critically acclaimed non-fiction films. Depardon did try his hand at another feature film in 2002 with Untouched by the West, a minimalistic epic about a young African hunter in the Sahara. Unfortunately, most of his work is rarely exhibited in the U.S. unless it is at a gallery installation or in conjunction with a museum exhibit.

Captive of the Desert was released on DVD in the PAL format from Arte Editions in February 2006. You might be able to still find copies from online sellers but you would need an all-region player to view it. A better option is to visit the website Cave of Forgotten Films where you can stream a very good copy of the movie with English subtitles.

Other links of interest:

https://www.artforum.com/features/direct-to-film-200782/