In 1969 French actor Jean-Louis Trintignant had three films in competition at the Cannes Film Festival, Costa-Garvas’s Z, Giuseppe Patroni Griffi’s Metti, Una Sera a Cena (Love Circle) and Eric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s, with the actor garnering critical praise for his performance in all three movies. When asked by an interviewer how it felt to be a potential prize recipient, Trintignant replied, “I’m not an award winner. I don’t have that affect to win Best Actor. You need a mad scene or a drunken scene or something like that. And in the films selected I don’t have any like that. All these roles are rather underwhelming. They’re ambiguous. They are complex but not remarkable. I’m not remarkable.” Typical of Trintignant, his response was self-deprecating but also shrewdly self-aware. The irony is that he did win Best Actor at Cannes for Z that year for playing the steadfast, non-partisan investigator of a highly political case. In fact, he built a career playing characters who were often hard to read, repressed or quietly self-possessed, and he made them endlessly fascinating for the viewer. This is just one of many insights shared by director Lucie Caries in Trintignant by Trintignant, an intimate documentary portrait of the actor that was made for French television in 2021, the year before he died. Even though the documentary is barely an hour in length, it pulls from more than 70 years of archival material, photos, interviews, TV and film clips and comments by fellow actors and directors to help dissect the enigma that is Jean-Louis Trintignant.

The actor was exceptionally handsome but he avoided being groomed as a French matinee idol and was drawn to complicated, often cerebral characters in serious dramas, thrillers and art house fare. Trintignant admitted that he was shy and introverted during his early years as an actor but in Caries’ documentary, you see what a chameleon he could be in interviews, going from being modest to wickedly funny to deeply philosophical in the course of a conversation.

Unlike many film documentaries on actors, Caries’s portrait is more interested in Trintignant’s approach to acting and his own thoughts on the profession and his career. It also takes a chronological approach to the major events in his life but keeps details about his private life to a minimum. Still, there is some little-known biographical information that is revealed along the way. For example, his mother raised him as a girl until he was five (she wanted a daughter, not a son). Trintignant was married three times but only his second wife Nadine is featured in the documentary and she often accompanied him with their children to his film sets. Of course, his image as a family man was of no interest to the tabloid press and is one reason he was able to maintain his privacy and low profile as a celebrity.

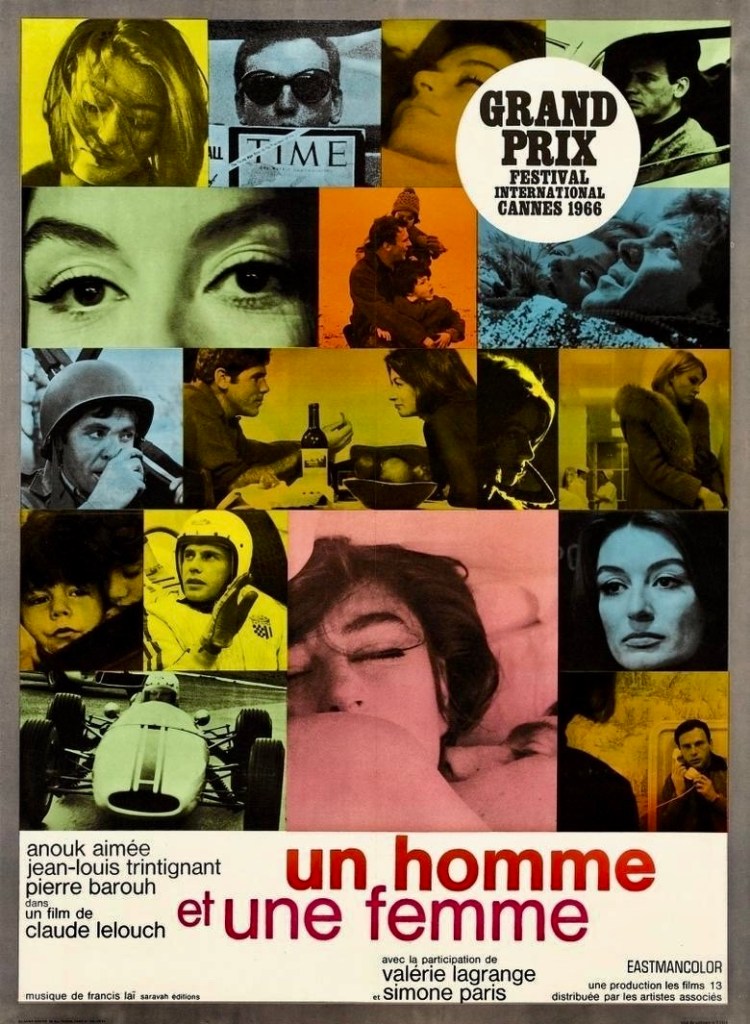

Trintignant also came from a family of race car drivers (on his father’s side). Although he had played the race car driver hero of Claude Leloach’s A Man and a Woman in 1966, Trintignant would actually start competing in car rallies later in life (not unlike fellow actor Paul Newman) and won second place at the 1981 24 Heures de Spa-Francorchamps event in Belgium at age 51.

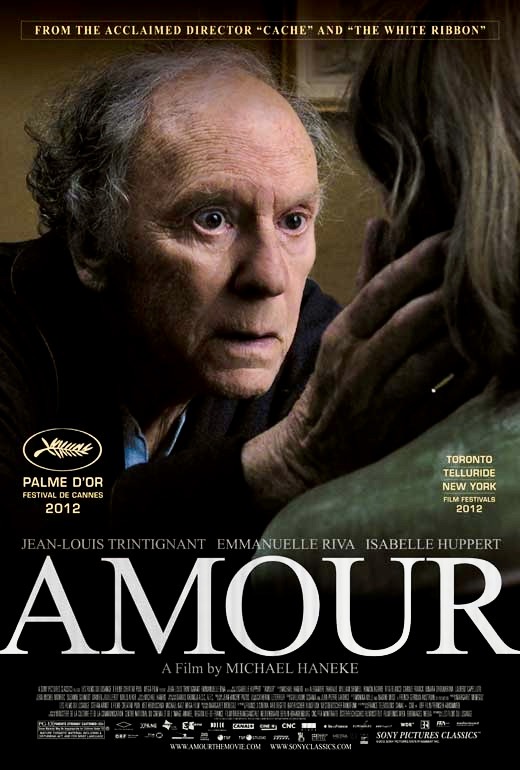

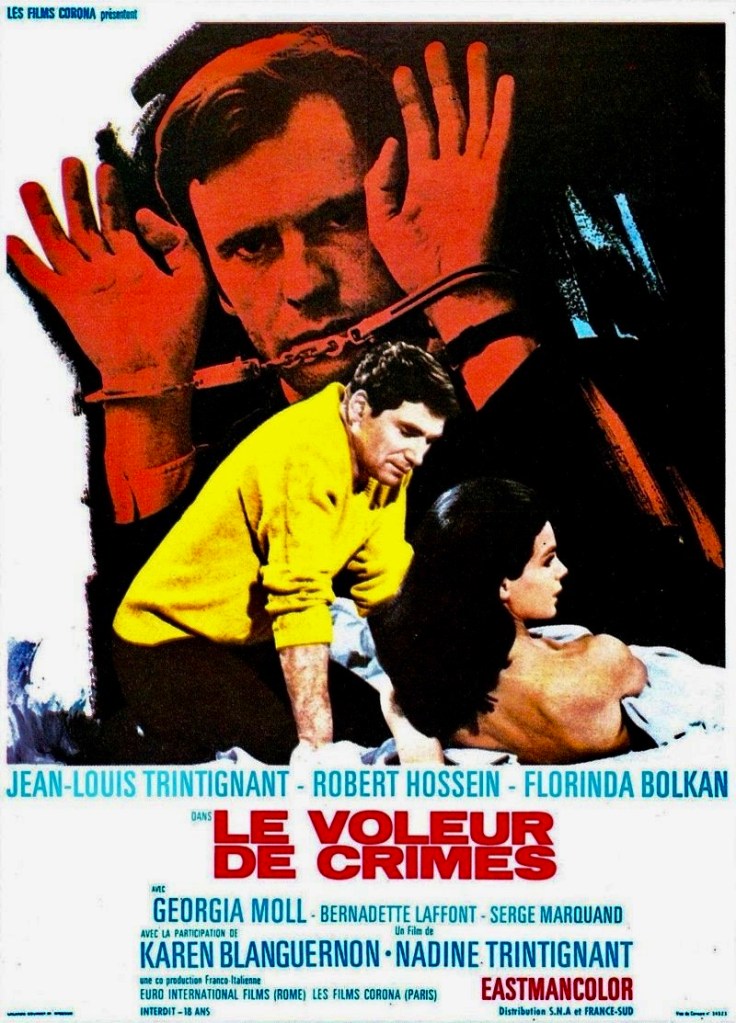

It is also worth noting that Trintignant made almost 150 movies in his lifetime (he died in June 2022 at age 91) but Caries only cherry picks a small but telling selection of clips to illustrate certain virtues and favorite roles of the actor. Among these are Z (1969), My Night at Maud’s (1969), The Conformist (1970), The Last Train (1973) opposite Romy Schneider, and Michael Haneke’s Amour (2012). There is also some rarely seen behind-the-scenes footage from A Man and a Woman (1966), Crime Thief (1969), directed by his second wife, Nadine Trintignant, A Full Day’s Work (1973), the actor’s first directorial effort, and Jacques Audiard’s crime drama See How They Fall (1994).

Of course, this only raises the question among fans of Trintignant about the absence of clips or focusing on high profile roles in Roger Vadim’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses (1959), Valerio‘s Zurlini’s WW2 drama Violent Summer (1959), Georges Franju’s murder mystery Spotlight on a Murderer (1961), Costa-Gavras’s The Sleeping Car Murder (1965), Trans-Europe Express (1966), the first of four film collaborations Trintignant would make with avant-garde novelist/screenwriter/director Alain Robbe-Grillet, Claude Chabrol’s Les Biches (1968) opposite his first wife Stephane Audran, The Outside Man (1972), a rare, underrated English-language crime drama with Roy Scheider, Ann-Margret and Angie Dickinson, Francois Truffaut’s Confidentially Yours (1983), Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colors: Red (1994), Patrice Chereau’s Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train (1998) and Michael Haneke’s Happy End (2017), the penultimate film of his career.

Trintignant’s first brush with fame was in his third feature film, Roger Vadim’s …And God Created Woman (1956) in which he played Brigitte Bardot’s shy, inexperienced husband. Offscreen the two actors had an affair and the press became more obsessed with that than the actual film. Trintignant’s immediate response was to sign up for military service which kept him off the screen for three years. “My memories of that time are terrible. My military service was very unpleasant, wretched. I was a little older…I did my military service at 26 while the rest were 20…six years isn’t a lot but it is at that age. The Algerian War was called the “Pacification of Algeria.” It’s something you can maybe accept when you’re 20 but you no longer do at 26…When I finished military service, I didn’t speak for six months. I was empty inside. It had broken me.”

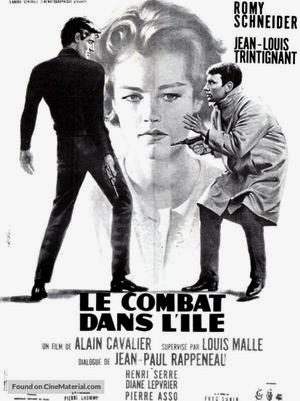

What Trintignant doesn’t reveal in the documentary is that he was constantly bullied by military officers because of his privileged background (he was the son of a wealthy factory owner) and he sided with the Algerian National Liberation Front. When he returned to acting, he would often be attracted to political themed subjects, regardless of whether he was playing a left wing radical or a conservative extremist as he did in Alain Cavalier’s Le Combat dans I’ile (1962), which is featured in a brief clip. “I’m interested in a film’s political scope,” Trintignant added, “I’d happily play a role contrary to my political stance. Politically I’m left wing. I’m very left wing at that.”

One of his first major critical triumphs was Mauro Morassi and Dino Risi’s Il Sorpasso (The Easy Life, 1963), in which he played an introverted law student who is befriended by an exuberant loudmouth (Vittorio Gassman) and comes out of his shell and starts to loosen up. It would also mark the beginning of Trintignant looking outside the French film industry for acting opportunities. By the mid-sixties, he was appearing regularly in a number of Italian productions such as Tinto Brass’s pop psychedelic thriller I Am What I Am aka Deadly Sweet (1967), Giulio Questi’s bizarre giallo Plucked (1968), the sex farce The Libertine (1968) and the cult spaghetti western The Great Silence (1968) in which he played a mute gunfighter.

Caries said in an interview that her intention in making Trintignant by Trintignant was to “create a dialogue between the Trintignant of yesterday and today.” It is certainly the first time I have ever seen the actor being so frank and candid in interviews. “By delving into his archives,” Caries said, “I realised that he had been interviewed countless times at different points in his career. It seemed natural to give him the floor and let his voice accompany the viewer. Of course, you never really know when he is being completely sincere and when he is just kind of pranking us.” At the same time, you realize how much personal tragedy has played a part in influencing the actor’s performances and world view. It was during the shooting of Bertolucci’s The Conformist that his infant daughter Pauline died.

In the documentary, Trintignant recalls “The film was being shot in Rome. While shooting I lost a child. One morning I got up and I was supposed to be on set. She was a year old. I found her dead in her cot. When a child dies, there’s no plan for that so I had to keep shooting, not that day but the next so I was hurting for almost the entire film….We’re actors. That’s what makes us great and at the same time, we’re worthless. It’s laughable because acting at times like that is just ridiculous, pathetic. But if you’re going to be an actor, you have to commit to it.”

Certainly the death of Pauline had a profound effect on Trintignant but the actor would suffer another tragedy in 2003 when his actress daughter Marie (Story of Women, White Lies) was beaten to death by her boyfriend Bertrand Cantat, lead singer and guitarist of the rock group Noir Desir. Trintignant later admitted he contemplated suicide for a while and retired from acting. He was eventually persuaded to return to the profession by Michael Haneke, who cast him in Amour, which became one of the crowning achievements of Trintignant’s career.

It is interesting to look at Trintignant’s career in comparison to the other two iconic French actors of his generation – Jean-Paul Belmondo and Alain Delon. Both of them were not just stars but mega celebrities, as famous for their off-screen lives as their screen personas. All three actors worked with some of the world’s most acclaimed directors during their early years but, as Belmondo and Delon grew older, they became more hands-on in terms of managing their own careers. Both became producers with a shrewd sense of their target audiences and concentrated more on making star vehicles and action/adventure/crime genre movies like Borsalino (1970) and The Professional (1981). They would still make the occasional art house movie but box office clout was more important to them. Trintignant, on the other hand, continued to challenge himself as an actor and, for my tastes, has a much more varied, eclectic and fascinating filmography in comparison.

Trintignant by Trintignant is highly recommended for fans of the actor and maybe someday it will be made available as a supplement or extra feature accompanying a Trintignant feature film on a disc, courtesy of The Criterion Collection or some similar prestige distributor.

Other links of interest:

https://www.newwavefilm.com/french-new-wave-encyclopedia/jean-louis-trintignant.shtml

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7835-jean-louis-trintignant-unshowy-and-unforgettable