Svaneti is not a planet in the solar system or some alternate universe out of a science fiction fantasy but it might as well be. In truth, it is a remote region located in the northwestern part of the Republic of Georgia on the southern slopes of the Caucasus Mountain range. For centuries the area was cut off from civilization due to its inaccessible location in the mountains plus the extreme weather, that usually included eight straight months of snowfall, also made it unwelcoming. After Georgia was invaded and annexed by the Soviet Union in 1922, the region was subjected to Stalin’s five-year plan (1928-1932), which was created to spawn agriculture collectives across the nation and introduce large-scale industrialization. But Svaneti was so isolated from the rest of the world that it took a while for Soviet workers to reach the area and Jim Shvante (Marili svanets) [English title: Salt for Svanetia (1930)] is a portrait of the lives and traditions of the Ushkul tribe in that inhospitable domain before the Soviets arrived to develop it. The result is not a typical documentary but more of a folk culture microcosm as captured by some wildly creative ethnographic filmmaker.

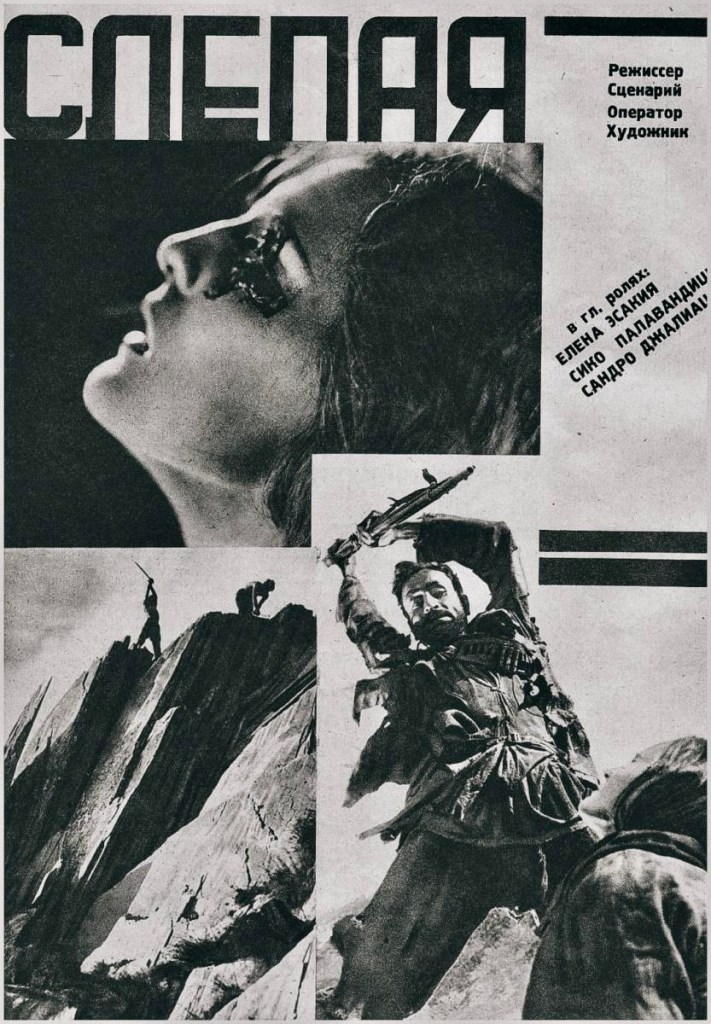

A quote from Vladimir Lenin, the first founding head of Soviet Russia, opens the film and sets the tone for what was intended as a propaganda film promoting the mandates of Soviet Russia leadership. Yet, almost everything that follows is an often bizarre depiction of unusual customs, tribal rituals and a punishing lifestyle that is eventually transformed in the final minutes of Salt for Svanetia by the arrival of progress as symbolized by a streamroller. Some critics have compared the film to Luis Bunuel’s Las Hurdes (aka Land Without Bread, 1933), a bleak portrait of poverty and hardship among peasants in a remote mountain village in Spain. Yet, some of the imagery is so surreal and disturbing that it could almost qualify as a precursor to Mondo Cane (1962) and other sensationalized films about aberrations of human behavior and cultural oddities from around the world. Like many films of that ilk, Salt for Svanetia was also scripted and several sequences were staged for the camera. In fact, the original plan was to film, produce and release a fictional drama about the region entitled Slepaia (English title: The Blind Woman), which focused on an orphan girl’s relationship with a wealthy family in Svaneti.

Poet, journalist and playwright Sergei Tretyakov was fascinated with the Svaneti region and wrote the screenplay for Slepaia, which was filmed and directed by Mikhail Kalatozov. Soviet authorities, however, withheld the film from release due to charges of formalism and a muddled thematic viewpoint. So Tretyakov and Kalatozov refashioned their concept as an ethnographical documentary about the Ushkul tribe of Svaneti utilizing their research and source material. They also used footage from an earlier documentary by Kalatozov and shots from another movie made in the region, Svanetia, or Serdtse gor (English title: The Heart of the Mountains, 1928) by filmmaker Yuri Zhelyabuzhsky.

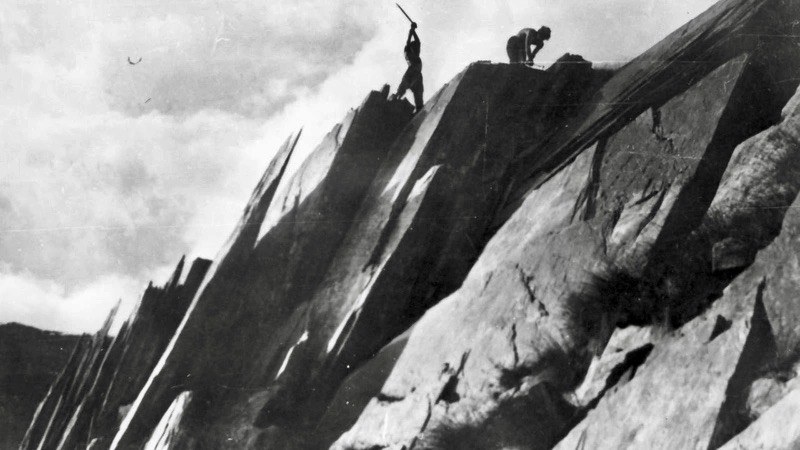

The bulk of Salt for Svanetia is an astonishing visual catalog of the hardships facing the lives of Ushkul tribal members. Most of the able-bodied men have left the region for better economical opportunities elsewhere so the remaining men, women and children are tasked with dawn to dusk physical labor – herding cattle and sheep, excavating slate from the rocky cliffs, harvesting the barley crop and defending the region from marauding land barons. The latter situation is dramatized in a montage where tribal members ascend the numerous stone towers created for defense and use rifles and hurl boulders at the invaders below.

Since Salt for Svanetia is a silent film, intertitles provide some context into what we are seeing but most of the Ushkul lifestyle revolves around the absence of salt and how they deal with that dilemma. Just as the tribal members require salt in their diet so do the cattle and sheep who represent their livelihoods. To remedy the situation, migrant workers from afar must carry bags of the precious mineral over treacherous terrain to reach Svaneti but it is never enough. The situation is so extreme that we see a cow licking up a man’s urine from the ground as well as a sheep consuming a few drops of salty sweat from a farmer’s neck.

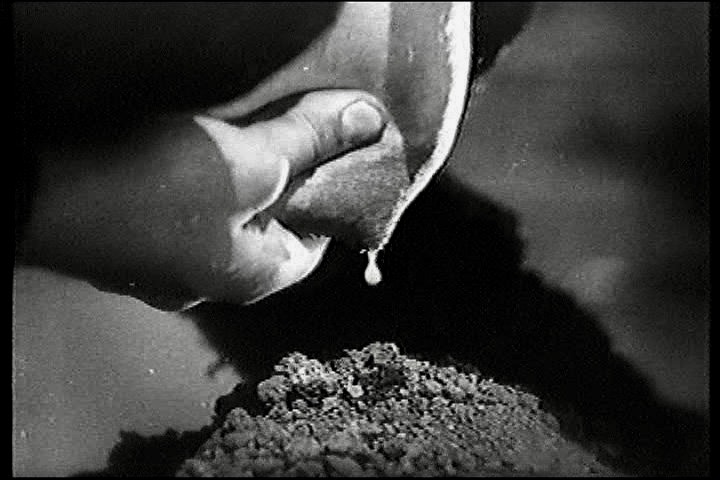

Although the salt crisis creates its own set of problems, the Ushkul tribe indulges in practices that often persecute members of their sect. For example, a funeral is a sacred ceremony that cannot be interrupted under any circumstances. As a result, a pregnant woman, who went into labor during the procession, is banished from the tribe. Later we see her grieving over her dead baby while squeezing drops of milk from her tit into the freshly dug grave.

Equally alarming is the treatment of animals in the Svaneti region. Oxen are slaughtered and their blood is spilled on the ground are part of the religious practices exercised during funerals. Likewise, a horse is forced to gallop at top speed until it dies from exhaustion – the purpose is also to honor the death of a villager.

One of the most distinctive aspects of Salt for Svanetia is the cinematography of Mikhail Kalatozov which, as noted in the Flicker Alley DVD program notes for the film, are a “preponderance of unorthodox framing, Dutch angles, inventive tracking shots and subjective hand-held circular movements.” The kinetic musical score by Zoran Borisavljevic is also a major asset in bringing an intensity and excitement to Kalatozov’s images. You can see how Sergei Eisenstein’s dynamic montage techniques for 1925’s Battleship Potemkin have been effectively utilized here. There is also a sequence toward the end of the movie where the glorification of the male form is celebrated as shirtless workers are shown building a road to Svaneti. In some ways, the filming of these muscular young men looks ahead to Leni Riefenstahl’s idealized depiction of the human body in Olympia: Part One and Olympia: Part Two (both 1938).

Kalatozov, of course, would go on to become one of Russia’s most prestigious filmmakers, who reached his peak in the late 1950s with the release of The Cranes Are Flying (1957), a poetic and moving anti-war drama which won the Palme d’Oro at the Cannes Film Festival and garnered a special mention for actress Tatyana Samoylova for her performance. Other key examples of Kalatozov’s work include Letter Never Sent (1960) about an ill-fated trip into the wilds of Siberia by four geologists searching for diamonds. I am Cuba aka Soy Cuba (1964) is a four vignette panorama of pre-revolutionary life in Cuba before Castro came to power, and The Red Tent (1969), is an international production about a failed 1928 expedition to the Arctic that starred Sean Connery, Peter Finch, Claudia Cardinale, Mario Adorf, Massimo Girotti and several Russian actors such as future director Nikita Mikhalkov and Grigoriy Gay.

When Salt for Svanetia was released in Russia, reviews were mixed with some government officials criticizing the film for focusing too much on the Ushkul tribe and not enough on the heroic efforts of Soviet Russia to bring progress to the region. These criticisms actually hindered Kalatozov’s career and it wasn’t until after Stalin’s death in 1953 that the filmmaker began to enjoy more creative freedom in his work. Yet, Salt for Svanetia is now recognized as a masterpiece by film scholars and critics. Here are just a few samples:

The Oxford Companion to Film: “Kalatozov’s documentary depicts with almost surrealist intensity the cultural conflict between pagan and Christian, and the social conflict between primitive and modern.”

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian: “This ballet of strangeness was Kalatozov’s natural response to the unknowability of a closed society, deeply different from his own. It was a creative reaction offered in good faith, and spoke unconsciously of the Soviet coloniser’s feelings in the face of the vast reach of the Soviet empire and all the peoples who were very different from the secular urban proletariat on whom the October Revolution was founded. A cine-poem of awe.”

Richard Brody of The New Yorker: “The film is a work of overt political propaganda, yet Kalatozov gives the impression of filming in a state of horror and shock.”

Geoffrey O’Brien of The New York Review of Books: “[A] sublime contemplation of Central Asian isolation and unforgiving folkways.”

For many years, Salt for Svanetia was largely unknown outside of the Soviet Union. The original negative was destroyed during the German invasion but copies were later found in Russia which were essential for the restoration efforts. The film can be seen in various formats today (there are even versions streaming on Youtube) but one of the best presentations is from Flicker Alley, which released it in July 2012 in their 4-DVD collection, Landmarks of Early Soviet Cinema, alongside such classics as Lev Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) and Dziga Vertov’s documentary Stride, Soviet! (1926).

Other links of interest:

https://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/cinema-and-theater/mikhail-kalatozov/index.html

Discover The Svaneti Region, Georgia’s Best Kept Secret