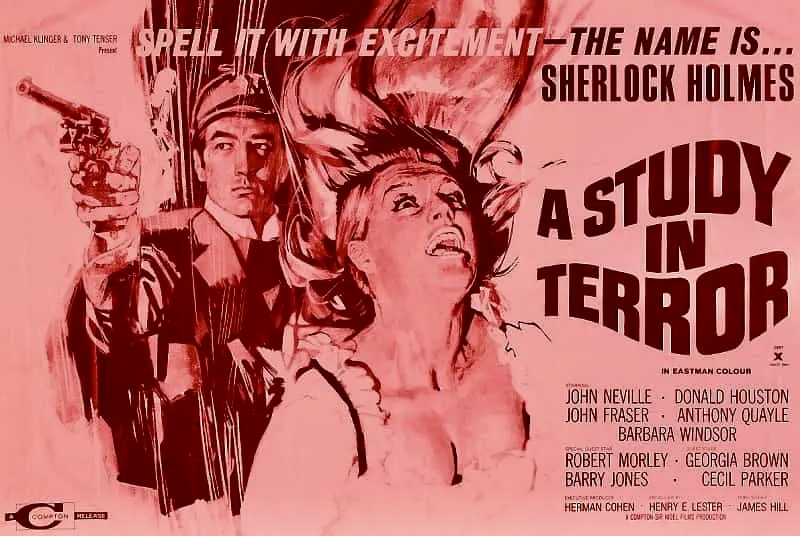

It seems surprising that Sir Author Conan Doyle’s most famous creation, Sherlock Holmes, and London’s most famous serial killer who stalked the Whitechapel neighborhood in 1888, were never brought together for one of Doyle’s novels. But the two were pitted against each other on screen for the first time in A Study in Terror (1966) and it’s one of the most underrated but entertaining entries among the Holmes-on-film mysteries created since the days of the Universal Basil Rathbone-Nigel Bruce series.

Since Doyle published his first Sherlock Holmes novel A Study in Scarlet in 1887, the year before the Ripper murders began, you’d think he would have incorporated this unsolved case into his Holmes novels at some point. It is possible that he used The Ripper as an inspiration for future villains in his detective fiction but there is something so intriguing about the idea of Sherlock Holmes emerging as a popular detective franchise at almost the same time the Jack the Ripper killings were happening. And one thing that distinguishes A Study in Terror is the mixture of fictitious characters with the real-life prostitute victims, some of whom like Annie Chapman, Catherine Eddowes and Elizabeth Stride are depicted on the screen.

Of course, anyone wanting to know anything about the real Jack the Ripper should look elsewhere because this mystery thriller is focused more on Holmes’ investigation and the many suspects that cross his path. The screenwriting team of Derek and Donald Ford (The Black Torment, Venom) take dramatic license with the known facts in the case, particularly in the depictions of the murders which become theatrical showpieces; the first victim has her neck skewered with a long knife, the blade protruding from one end, the knife handle from the other. Another prostitute is pushed into a drinking trough for horses and stabbed repeatedly while held underwater – we get different perspectives of the knifing above and under the water as the screen explodes in an almost psychedelic color palette of reds, pinks and blues (one of the telltale signs that A Study in Terror was made in the sixties despite the atmospheric period settings).

What makes A Study in Terror such a unique addition to the Sherlock Holmes filmography, besides the Jack the Ripper subplot, is the way it fuses the lowbrow with the highbrow. On one level, it has all the trappings of a sixties exploitation film with its emphasis on sex and violence in regards to the ill-fated whores. On the other hand, the film is a handsomely mounted production that rivals the best of Hammer Studios with its colorful art direction and evocative atmosphere. There is also a lush orchestral music score by John Scott complete with xylophone and bongos (another swinging sixties influence) and an impressive Masterpiece Theatre-like ensemble of award-winning British actors that reads like a “Who’s Who” of English cinema and is toplined by John Neville and Donald Houston giving new interpretations of Doyle’s Holmes and Watson characters. It’s an unlikely combination of elements that somehow jell.

Even more unlikely is the genesis of the project. By some accounts, Herman Cohen, the American screenwriter (How to Make a Monster, The Headless Ghost) and producer of such low-budget horror hits as I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957) and the grisly Horrors of the Black Museum (1959), claimed credit for coming up with the concept of Sherlock Holmes solving the Jack the Ripper case after meeting with Henry E. Lester, the legal representative for the Conan Doyle estate. Other sources credit the promising premise to Tony Tenser, who with his partner Michael Klinger, had produced a number of profitable exploitation pictures (The Yellow Teddy Bears, London in the Raw) under their company Compton-Tekli and were recruited by Cohen as independent producers for A Study in Terror. Tenser and Klinger had recently financed Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) and it was their first art house success and critically acclaimed feature so they envisioned their Holmes tale as a prestige production. Originally titled Fog (Columbia Pictures management didn’t like the title and forced Cohen to retitle it), the film was directed by James Hill, a rising young talent in the British film industry who got overlooked in England’s New Wave cinema movement despite his well received slice-of-life drama, The Kitchen (1961). Hill’s biggest success would occur immediately after A Study in Terror; he was tapped to direct Born Free (1967) which earned him a DGA nomination from the Directors Guild in America.

While the premise of Sherlock Holmes vs. Jack the Ripper is a swell one, it’s the cast that makes A Study in Terror required viewing for anglophiles. Not only do such veteran character actors as Cecil Parker (prominently featured in so many Alec Guinness comedies such as The Man in the White Suit [1951] and The Ladykillers [1955]) and Kay Walsh (the former Mrs. David Lean who played Nancy in his 1948 version of Oliver Twist) turn up in minor supporting roles but so do newcomers like Colin Redgrave (in a brief pub scene) and Judi Dench as Sally, an angel of mercy who assists her uncle, Doctor Murray (Anthony Quayle), in his work.

Horror film fans will recognize Chunky, the slaughterhouse worker played by Terry Downes as the same actor who played the hunchback servant in Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers (in real life, Downes was a former world middleweight boxing champion) and Adrienne Corri has been attractively showcased in The Hellfire Club, Moon Zero Two, Vampire Circus and is probably best known as the unfortunate gang rape victim in A Clockwork Orange (1971). John Fraser, who plays Lord Carfax, will be recognizable to many as the persistent, ill-fated suitor of Catherine Deneuve’s psychotic shut-in in Repulsion from the year before.

There are also scene chewing bits by Avis Bunnage (The L-Shaped Room, Tom Jones) as an irate landlady, German actor Peter Carsten (The Secret of the Black Trunk, Web of the Spider) as a surly bartender and possible murder suspect, Oscar nominated actor Frank Finlay (Othello [1965]) as Inspector Lestrade, and Georgia Brown (a former member of the jazz group Lambert, Hendricks & Ross and Broadway musical star of Oliver!) as the tavern singer belting out “These Hard Times” and “Tra-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-Ay,” one of those maddening beerhall numbers that lend themselves to naughty lyrics: “Did you get yours today? I got mine yesterday. That’s why I walk this way….” or “My knickers flew away. They went on holiday. They came back yesterday…”

Robert Morley turns up as Mycroft Holmes, Sherlock’s older brother, and it is one of the few times his character is depicted in screen versions. Anthony Quayle as Doctor Murray, the committed, workaholic slum surgeon, is one of the more compelling suspects and it’s a great role for him but the most conspicuous supporting player in the entire cast is John Cairney (The Flesh and the Fiends, Jason and the Argonauts) as Dr. Murray’s furtive, ghostly assistant Michael. Whenever he’s on screen, skulking or shuffling around the edges of the frame like David Bruce’s The Mad Ghoul, you can’t take your eyes off him. What is up with this guy? He upstages everyone without one word of dialogue because he is such a bizarre screen presence.

Of course, no discussion of A Study in Terror can exclude mention of John Neville and Donald Houston who are the real stars of the film. This was Neville’s only opportunity to play Holmes on screen and it’s an impressive portrayal once you warm to his slightly caffeinated rhythm. Neville plays Holmes like a clock that’s wound a little too fast but by the middle of the film his somewhat robotic manner has been tempered and humanized by a sly sense of humor and cynicism toward authority figures. Donald Houston is less memorable as Watson but, according to various sources, the actor was determined not to play Holmes’s friend and companion as comic relief in the manner of Nigel Bruce. While he avoids the bumbling, affectionate caricature of Watson in the Universal series and occasionally even displays ballsy behavior such as engaging in a back alley brawl or angrily confronting a murder suspect, he is still a man too easily awed by Holmes’ brilliance and rarely the initiator in any action that could lend to solving the case.

It is a shame that Neville didn’t return to the Holmes character on screen because he makes a dashing hero that has the same sense of style Patrick Macnee brought to his John Steed character in The Avengers TV series. Neville did, however, appear as Holmes again but on the stage in a production of William Gilette’s play Sherlock Holmes. Ironically, he had been the original choice to play Holmes in the Broadway musical Baker Street in 1965 but had to turn it down due to other commitments (Fritz Weaver won the part). For most of his career, Neville has been more active on the stage than in movies but is probably best known for playing the title role in Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchhausen [1988] and for numerous appearances on TV’s The X-Files.

A Study in Terror was not a box office hit when it was released – and the main reason the Neville-Houston pairing didn’t lead to a sequel – but it did manage to garner a number of positive reviews. In the British press, The Sun reported: “Directed by James Hill, with plenty of boozy, bawdy, beautiful period atmosphere, Study emerges as a vastly entertaining juggling act between truth and fantasy.” The Daily Express noted “…James Hill..has recreated the atmosphere of Edwardian London with uncanny success, so that not only does every Whitechapel scene look like the noisome slum it undoubtedly was, but also seems to smell of gin and cheap perfume…John Neville plays the supercilious and self-confident Sherlock Holmes with just the right touch of hauteur.” The Daily Worker added “The gruesome ripping up of bodies isn’t exactly Holmes’ cup of blood. But the two approaches to crime are entertainingly married in Study which is more in fun than in deadly earnest.”

The film also found favorable support in the U.S. press from Time which called it a “stylish send-up of costume chillers as well of that silly ass with the deerstalker and the magnifying glass…John Neville and Donald Houston play Holmes and Watson with a quaint and slightly stilted charm that defines them as exactly what they are: impressive pieces of Victorian bric-a-brac.” The New York Times reported that “the entire cast, director and writers, play their roles well enough to make wholesale slaughter a pleasant diversion,” and Films in Review added that “John Neville is a credible Holmes, and the direction of James Hill, the production design of [Alex] Vetchinsky, and the costumes of Motley, lift this inexpensive black-&-whiter [was it actually released in a black and white version in some markets?] above the level of routine entertainment.”

So why wasn’t A Study in Terror a success? It had all the necessary ingredients for a mystery thriller and was made long enough after the Basil Rathbone series not to invite immediate comparisons. The advertising campaign certainly didn’t help, trying to mimic TV’s campy Batman series: “Here comes the original Caped Crusader!” or adding exclamatory words to the poster such as “Pow! Crunch! Aiiieee!” Perhaps audiences in the sixties were too distracted by the current film fads of James Bond, the British invasion and more permissive contemporary films (I, a Woman, Inga) to care about a period thriller set in Edwardian times. The gimmick of Sherlock Holmes tracking Jack the Ripper didn’t end here though. The premise would resurface in Murder by Decree, directed by Bob Clark, which actually recast Frank Finlay as Inspector Lestrade and Anthony Quayle in the role of Sir Charles Warren with Christopher Plummer as Sherlock Holmes and James Mason as Dr. Watson. It was probably the most critically acclaimed and prestigious film by Bob Clark, the director most famous for Porky’s, Black Christmas and A Christmas Story and, like A Study in Terror, it wasn’t a box office success.

Like the James Hill film, Murder by Decree presented the theory that Jack the Ripper was an aristocrat with possible ties to the Royal Family. This popular idea first emerged in 1962 when biographer Philippe Jullian mentioned that a popular rumor at the time of the murders inferred that Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale was the Ripper. Producer Herman Cohen came up with a similar theory when he visited Scotland Yard’s Black Museum where he discovered that “Queen Victoria sealed some secret documents on the case of Jack the Ripper…it all points to a member of the the Royal Family. That’s why we did what we did. We didn’t want to get too close to the Royal Family, but we made the Ripper an aristocrat.” So, in this respect A Study in Terror was the first Jack the Ripper film to take this new suspect line.

A whole post could be devoted, of course, to Jack the Ripper in the movies and there have been countless films where he is either the main subject (the various versions of The Lodger [1927, 1932 or 1944], Man in the Attic [1953] or the self-titled 1959 release directed by Robert S. Baker and Monty Berman) or a supporting character (Pandora’s Box, The Ruling Class). I’m not even sure why I have always been fascinated by the case. If his identify had been revealed, would Jack the Ripper still interest me? Probably not. There’s something about an unsolved case that keeps the mind engaged, searching for clues, suspects or closure.

I will say that during a trip with my wife to London several years ago, one of the highlights was a late night, Jack the Ripper walking tour of the Whitechapel neighborhood conducted by Donald Rumbelow, author of The Complete Jack the Ripper and a former policeman and curator of London’s Black Museum. We even ended the tour in The Ten Bells pub where a few of the Ripper’s victims spent their final hours before being murdered. It was a fun but creepy crawl through a section of London that still feels deserted and unsafe on a foggy night and A Study in Terror brought all this back to me. Perhaps one day someone will make the ultimate Sherlock Holmes vs. Jack the Ripper movie. In the meantime, Sherlock Holmes vs. Jack the Ripper is better known and more popular as a video game.

Over the years A Study in Terror has been released on VHS and DVD but it wasn’t until April 2018 that a domestic release from Sony Pictures appeared on Blu-ray. It contains no extra features and is still your best option for purchasing the movie.

Other links of interest:

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Jack-the-Ripper/

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-james-hill-1442251.html

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8933087/The-Dam-Busters-star-John-Fraser-dies-aged-89.html