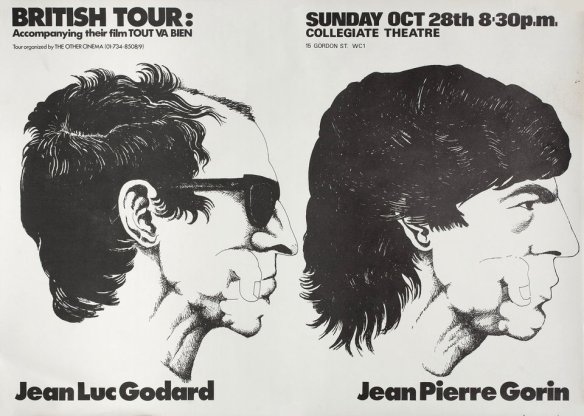

With more than 100 feature films, shorts, video and TV work to his credit, Jean-Luc Godard is surely the most audacious, groundbreaking and prolific filmmaker from his generation. Even longtime admirers and film historians have probably not seen all of his work and some of it like the political cinema he made with Jean-Pierre Gorin under the collaborative name Groupe Dziga Vertov is tough going for even the most ardent Godard completist. Weekend (1967) is generally acknowledged as the last film Godard made before heading in a more experimental, decidedly non-commercial direction which roughly stretched from 1969 until 1980 when he reemerged from the wilderness with the unexpected art house success, Sauve qui peut (Every Man for Himself). But most of the work he made during that eleven year period prior to 1980 championed social and political change through ideological scenarios and leftist diatribes that were overly cerebral and static compared to earlier career milestones like Breathless (1960), Contempt (1963) and Pierrot le Fou (1965).

With more than 100 feature films, shorts, video and TV work to his credit, Jean-Luc Godard is surely the most audacious, groundbreaking and prolific filmmaker from his generation. Even longtime admirers and film historians have probably not seen all of his work and some of it like the political cinema he made with Jean-Pierre Gorin under the collaborative name Groupe Dziga Vertov is tough going for even the most ardent Godard completist. Weekend (1967) is generally acknowledged as the last film Godard made before heading in a more experimental, decidedly non-commercial direction which roughly stretched from 1969 until 1980 when he reemerged from the wilderness with the unexpected art house success, Sauve qui peut (Every Man for Himself). But most of the work he made during that eleven year period prior to 1980 championed social and political change through ideological scenarios and leftist diatribes that were overly cerebral and static compared to earlier career milestones like Breathless (1960), Contempt (1963) and Pierrot le Fou (1965).

Yves Montand (center in raincoat) and Jane Fonda (lower right) star in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972).

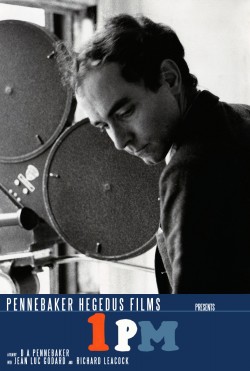

Of the films he made during the Groupe Dziga Vertov period, only Tout Va Bien (1972), which starred Jane Fonda and Yves Montand, attracted mainstream critical attention but most of the reviews at the time were indifferent or hostile to this Marxist, Bertolt Brecht-inflluenced polemic about a workers’ strike at a sausage factory. Much more interesting to me was the film he attempted to make in 1969, tentatively titled 1 AM (or One American Movie). A collaboration with cinema-verite pioneers D. A. Pennabaker and Richard Leacock, the project was abandoned after Godard lost interest during the editing phase but Pennebaker ended up completing his own version of the existing footage which he titled 1 PM (or One Parallel Movie). This is a brief history of the film’s journey from concept to screen.

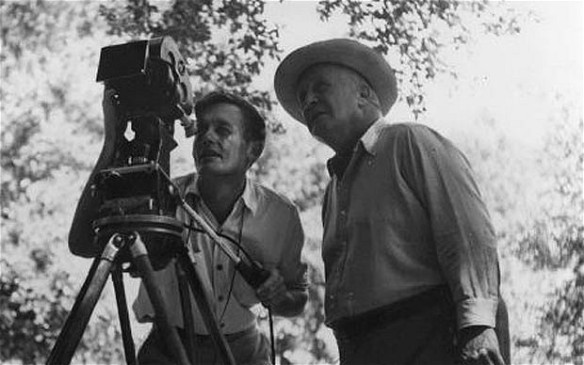

The genesis for 1 AM can be traced back to the early 1960s when Godard first encountered such cinema verite works as Robert Drew’s Primary (1960), which followed presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Hubert H. Humphrey as they campaigned during the 1960 Wisconsin primary. Richard Leacock and Albert Maysles served as cinematographers on Primary with D.A. Pennebaker serving as sound recordist and sequence editor; All three would go on to become major figures in the cinema verite movement but Godard was suspicious of this new approach to documentary filmmaking. In fact, he had criticized Leacock in print on aesthetic grounds for promoting the idea that you could capture reality in the raw without acknowledging the presence of the camera or a crew. Godard also attacked Primary for its inability or disinterest in shedding light on how the U.S. political process worked.

Cinematographers Richard Leacock (left) and D.A. Pennebaker in Monterey, California circa 1967. Courtesy: D.A. Pennebaker.

Despite this, Godard remained curious about the direct cinema movement (cinema verite) and when he met Pennebaker in the early 1960s at the Cinémathèque in Paris, he proposed a potential film collaboration with Pennebaker and Leacock. “The idea was that [Godard] would go to a small town in France,” Pennebaker recalled (in D.A. Pennebaker by Keith Beattie) and he would rig it with all kind of things happening: people would fall out of windows, people would shoot other people, whatever. We would arrive one day on a bus or something with our cameras and then film whatever we saw happening around us.”

Jimi Hendrix electrifies the crowd at the 1967 Monterey Pop festival, which was filmed by D.A. Pennebaker and released in 1968 as the concert film, Monterey Pop.

That project never materialized but a turning point occurred in 1968 with the release of Monterey Pop, directed and filmed by Pennebaker with contributions from Leacock, Maysles and others. This historic record of the 1967 three day concert event at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in California featuring Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and others was a resounding commercial success and enabled Pennebaker and Leacock to add a distribution outlet to their production company. As a result, they acquired the U.S. rights to Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) and brought him to America in 1968 to tour with the film at selected openings.

Juliet Berto plays a French student turned terrorist in Jean-Luc Godard’s absurdist political comedy, La Chinoise (1967).

It was during his U.S. visit that Godard became convinced that America was on the brink of a societal breakdown. With Pennebaker and Leacock employed as his cameramen, Godard began shooting footage for a new film tentatively titled 1 AM which would be both a portrait of contemporary America but also a meditation on documentary and fictional approaches to cinematic representations. Originally Godard planned to structure the film in ten sequences: “Five reality scenes, in which subjects recount their experiences, and five fictionalized counterparts in which actors would speak a transcript of the words spoken in the “documentary” scenes.” (from D.A. Pennebaker by Keith Beattie).

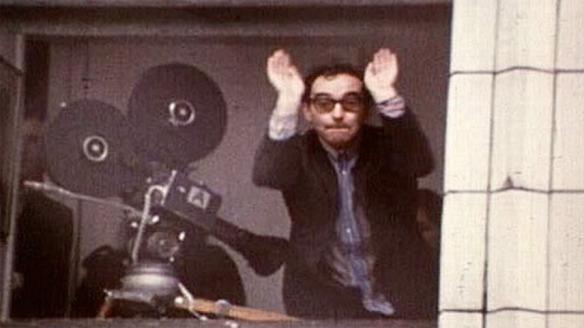

Jean-Luc Godard gives Rip Torn (off camera) instructions on what to do during a classroom visit with New York students in the film, 1 PM (shot in 1969, released in 1971).

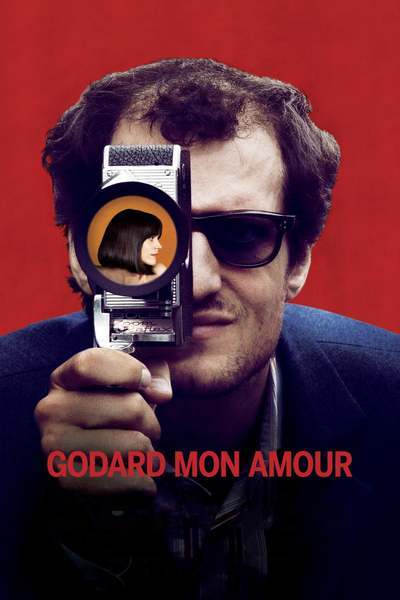

During filming, Godard begin to deviate from his original plan by replacing some of his original interview subjects with last minute improvisations. For example, Godard initially wanted to interview a woman who worked on Wall Street as a way to critique gender and social status in a location synonymous with U.S. economic power. Instead, he chose to interview Carol Bellamy, a lawyer for the Chase Manhattan Bank, who later became problematic during the editing process. Godard also dropped the idea of interviewing a young girl on the streets of Harlem and substituted it with a sequence shot in a predominantly African-American elementary school in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville neighborhood of New York. Other participants/interviewees in the film included actor Rip Torn, Black Panther party member Eldridge Cleaver, poet/playwright Leroi Jones (aka Amiri Baraka), former Chicago Seven defendant/political activist Tom Hayden and members of the Jefferson Airplane. There are also lots of candid and revealing shots of Godard, chain smoking and looking high strung and intense throughout the shoot, brief cameos by Pennebaker and Leacock and fleeting glimpses of French actress Anna Wiazemsky, Godard’s wife at the time, who was relegated to the background during the filming according to Pennebaker. A new film by Michel Hazanavicius, Godard Mon Amour, covers this same time period and is based on Wiazemsky’s autobiography Un an Apres, which goes into detail about the troubled marriage of Godard and his child bride. The filmmaking process for 1 AM was dictated by Godard’s specific technical instructions to his cinematographers. “We’d have these four-hundred-foot magazines, which would be ten minutes of film,” Pennebaker said in a 2011 interview for the A.V. Club. “We would shoot them continuously; we wouldn’t stop. We would figure out a scene that we were going to cover and we would shoot four hundred feet in one continuous roll, and we would never edit it…That was the plan.”

The filmmaking process for 1 AM was dictated by Godard’s specific technical instructions to his cinematographers. “We’d have these four-hundred-foot magazines, which would be ten minutes of film,” Pennebaker said in a 2011 interview for the A.V. Club. “We would shoot them continuously; we wouldn’t stop. We would figure out a scene that we were going to cover and we would shoot four hundred feet in one continuous roll, and we would never edit it…That was the plan.”

Alfred Hitchcock on the set of Rope (1948) with James Stewart (far right), Farley Granger (far left) and John Dall.

Although it sounds like the approach Alfred Hitchcock utilized for his 1948 thriller Rope, 1 AM quickly deviated from the dictates of the ten-minute magazine format. Pennebaker discovered that simply filming an interviewee was not interesting enough to engage sustained interest and he began to capture details of the milieu such as crew members on set, random close-ups and glimpses of friends and associates watching the filming or the odd detail like two young African-American girls singing along with a tape recorder as they skip along the waterfront.  Godard began to realize that the disruptive social revolution he anticipated in America was never going to happen and he moved on to other projects with a new collaborator, Jean-Pierre Gorin. Because Pennebaker had signed a contract with PBL, a forerunner of Public Television, which had provided the funding for One A.M., the filmmakers were obliged to deliver a completed film so Godard returned to the U.S. to review the footage in March 1970. Godard later remarked, “When [Gorin and I] first arrived [and looked at the rushes] I had thought we could do two or three days’ editing and finish it, but not at all. It is two years old and completely of a different period.” (from D.A. Pennebaker by Keith Beattie).

Godard began to realize that the disruptive social revolution he anticipated in America was never going to happen and he moved on to other projects with a new collaborator, Jean-Pierre Gorin. Because Pennebaker had signed a contract with PBL, a forerunner of Public Television, which had provided the funding for One A.M., the filmmakers were obliged to deliver a completed film so Godard returned to the U.S. to review the footage in March 1970. Godard later remarked, “When [Gorin and I] first arrived [and looked at the rushes] I had thought we could do two or three days’ editing and finish it, but not at all. It is two years old and completely of a different period.” (from D.A. Pennebaker by Keith Beattie).

1 AM was declared officially dead by Godard and Pennebaker recalled on his website phfilms.com that Godard went off with Jean-Pierre Gorin “to start a new leftist cinema and Leacock [went off] to teach at MIT. I was left to deliver something to Public Television or face severe contractual coercion. Thus, 1 AM became 1 PM (One Parallel Movie – or One Pennebaker Movie, as Jean-Luc has called it.)

“Ricky had filmed pretty much what Godard wanted, but I was the extra camera that nobody noticed, and I filmed whatever looked interesting. So when I began putting the sequences together as Godard had suggested, I saw a lot of stuff I’d shot that hadn’t been planned, and I was soon making a film of my own. I doubt it was the film Godard had in mind when we started, but then, it seldom works out that way anyhow. I found what happened entertaining and filled with surprises. It’s some sort of history. I’m grateful to Jean-Luc, Ricky and everyone who showed up to see what would come of this crazy idea, and I am continually amazed that such a film would ever get made.”

Cinematographer/director D.A. Pennebaker captures a live performance of street musicians in Harlem in 1 PM (1971).

Pennebaker’s creation, 1 PM, remains an unclassifiable movie that is a fragmented, crazy quilt of street theater, cinema verite reportage, concert film and radical agitprop. It can be maddening and self-indulgent but also fascinating and laugh-out-loud hilarious at times. And, most of all, it is an invaluable time capsule of America in the sixties as reflected through the polarizing presences of its on-camera participants. The final sequence, in which the Jefferson Airplane performs “House at Pooneil Corners” from the rooftop of the Schuler Hotel, is a fun, impromptu musical happening which prefigures the rooftop concert captured in the closing moments of The Beatles’ 1970 film, Let It Be. We see New Yorkers on the streets, looking out of office windows and driving by in cars clearly surprised by the unannounced open air concert. Then the cops arrive to shut things down. Singer Grace Slick would later remark, “We did it, deciding that the cost of getting out of jail would be less than hiring a publicist.”

Grace Slick and the Jefferson Airplane give an impromptu rooftop performance in New York City in the closing moments of D.A. Pennebaker’s 1 PM (1971).

Pennebaker opens 1 PM with this disclaimer: “This film was begun in 1968. However Godard never completed the editing of it. I have assembled the rushes of the scenes we filmed with as little editing as possible to fit the original plan. I have also added a few scenes that were really notes I filmed during the shooting. The Leroi Jones street mass was not meant as part of the film. This is not the film Jean-Luc intended as One American Movie (1 AM). Rather he called it a parallel movie (1 PM).”

Rip Torn goes Native American while spouting the political opinions of Chicago Seven defendant Tom Hayden in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1 PM (1971).

Considering the circumstances surrounding 1 PM, you wouldn’t expect it to be as entertaining as it is but Rip Torn as court jester/chief provocateur is a major asset. Whether he is wandering through the woodlands in Native American garb reciting bits of Tom Hayden rhetoric or trying to provoke African-American students into attacking him verbally or physically as he struts around a classroom dressed as a Confederate soldier, Torn is an undeniably flamboyant, showboating presence. And it is fascinating to see Godard giving Torn instructions on how to deliver excerpts from some of the interviewee speeches and what Torn does with them; the elevator sequence, in particularly, has a poetic flow to it as Torn shouts out non-sequitur phrases like “The university is a supply line!,” “People in Factories!,” or “People have no respect for the people who are demanding respect!” This is street theater for the ages.

New York classroom students are both bemused and suspicious of Rip Torn as he tries to prod them into reacting against his Confederate soldier costume in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1 PM (1971).

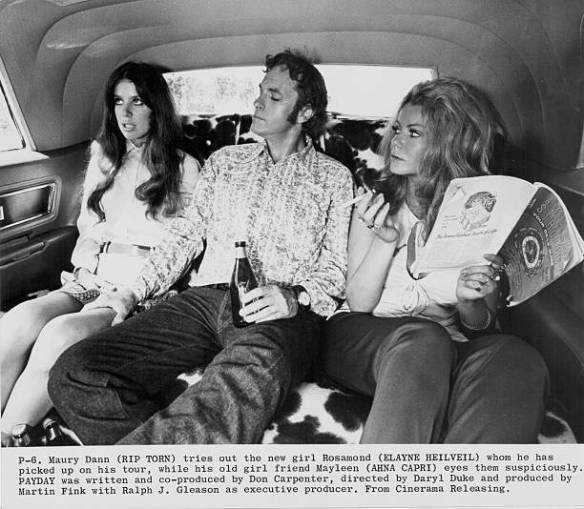

Torn is also capable of looking foolish and self-congratulatory as when he attempts to “school” African-American students on how corporate America is their enemy; candid shots of kids in the classroom clearly indicate that most of the students are hip to Torn’s manipulations and could probably teach him a thing or two about race and discrimination. Yet, Torn remains one of the most underrated and adventurous film and stage actors of our time and some of the movies he made between 1968 through 1973 show Torn in his prime in edgy, defiantly non-Hollywood indies like Norman Mailer’s Beyond the Law (1968), Agnes Varda’s Lions Love (1969), Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart (1969), Joseph Strick’s Tropic of Cancer (1970), where Torn plays controversial author Henry Miller during his Paris heyday, and Daryl Duke’s Payday (1973), which should have garnered Torn a Best Actor Oscar nomination as a lecherous, self-destructive country singer named Maury Dann.

Country singer Maury Dann (Rip Torn) puts the moves on Rosamond (Elayne Heilveil) while his mistress Mayleen (Ahna Capri, right) watches in disbelief in Payday (1973), directed by Daryl Duke.

Around the same time, Torn’s off-screen life seemed just as volatile as some of the screen characters he played. He was originally considered for the role that eventually went to Jack Nicholson in Easy Rider but lost the part after a heated confrontation with Dennis Hopper at a New York dinner party. Hopper’s allegation that Torn pulled a knife on him during the argument was later proven false as witnesses in a court case confirmed that Hopper was the one welding the knife. Torn ended up winning the lawsuit to the tune of $475,000 with the option of taking Hopper to court for punitive damages.

Rip Torn attacks Norman Mailer in a scene from Maidstone (1970) that crosses over from acting into genuine aggression.

Torn was back in the news again for attacking Norman Mailer on screen with a torn hammer in Maidstone (1968), another homemade Mailer indie about an arthouse pornographer who runs for President of the U.S. The scene exists in the script but Torn’s frustration and anger toward director/actor Mailer during production erupts into a real on-camera fight in Maidstone that gives the movie some needed frisson in the final moments. The two men later reconciled but Torn’s persona as an unpredictable force of nature is supported by documented incidents like the above.

Director Jean-Luc Godard and Tom Hayden at a speaking event in Berkeley, California is featured in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1 PM (1971).

As for the other participants in 1 PM, Tom Hayden is probably the least engaging although his political insights ring true to the times despite the dated rhetoric. While viewing some rushes with Godard in the movie, Hayden complains that he finds the filmmaking process distracting and partly to blame for his stiff, unnatural delivery of a speech in someone’s backyard in Berkeley, California. To his surprise (and possible regret), Hayden is informed by Godard that depicting the unnatural act of filmmaking was paramount to his vision and the need to make it completely transparent to viewers.

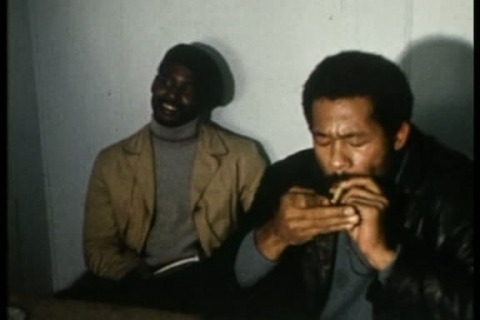

Eldridge Cleaver (smoking) is one of the famous featured interviewees in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1 PM (1971).

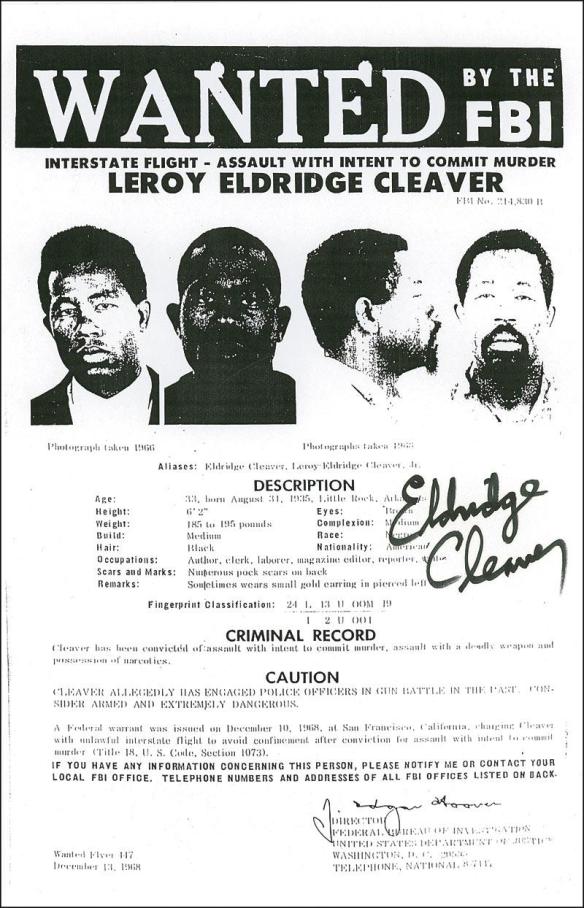

Eldridge Cleaver makes a more formidable interviewee and he exudes a laid-back but obvious contempt for the filmmakers, stating that the time has come to shoot guns, not film. Cleaver cites having bad experiences with previous media representatives and says point-blank, “You’re part of that mafia…all kinds of shark and cutthroats have come here [to the projects] with their fucking cameras and broadcasters and when we see the cameras we want to kick the cat’s ass and break his camera. That is why when you started asking around about that you ran into a stone wall. We don’t like to talk to the news media anymore…but we’ll see how we come out on this, you know.”  According to some sources, Cleaver, who was on bail for attempted murder, fled the U.S. just two days after this interview was shot and made his made to Algeria where he lived in exile until 1972 when he relocated to Paris. Cleaver eventually returned to the U.S. in 1977 to face the pending attempted murder charge.

According to some sources, Cleaver, who was on bail for attempted murder, fled the U.S. just two days after this interview was shot and made his made to Algeria where he lived in exile until 1972 when he relocated to Paris. Cleaver eventually returned to the U.S. in 1977 to face the pending attempted murder charge.

Director Jean-Luc Godard is captured on film by cinematographer D.A. Pennebaker during the making of 1 AM which was retitled 1 PM and credited to Pennebaker after Godard abandoned the film.

Of all of the interviewees, Pennebaker regrets the inclusion of Carol Bellamy as the Wall Street representative. “That she ever got put into the film really enrages me, because she is absolutely unnecessary to the film. We thought any business lady would have done, but we had to have this one, and somebody gave her a contract which allowed her to censor the whole film if she doesn’t like any part.” (source: a 1970 interview with G. Roy Levin). As a result, Bellamy was able to make Pennebaker delete a portion of her interview that made her inclusion in the film particularly relevant to Godard’s original intentions. The footage that remains of her in 1 PM functions more as a throwaway joke with the lawyer making some sweeping analogies about big business: “To ignore business [in society] is like treating a man for cancer and ignoring the fact that he has heart disease…In fact, I think business will play the largest role in the development of a new and better society in this country.” Easily the most interesting aspect of the Wall Street section is the scene where Godard and his crew are stopped by a Chase Manhattan security guard who is clearly suspicious of this dapper but nervous looking Frenchman and his cameramen. Miraculously, they get clearance to shoot in the lawyer’s office (Too bad they couldn’t end up using the good stuff.)

Anne Wiazemsky makes a fleeting appearance next to her husband, Jean-Luc Godard, in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1 PM (1971).

1 PM is currently not available on any format through an authorized distributor but you can view it for free on the internet. You can also find acceptable DVD-R bootlegs of the film from various sources. The film occasionally pops up at repertory screenings such as a recent February 2018 screening at NYC’s Film Forum as part of a cinema verite festival. The film is essential viewing for anyone interested in the cinema of Jean-Luc Godard, America in the sixties or the direct cinema movement. Richard Brody, film critic for The New Yorker, proclaimed 1 PM as an “exemplary, fascinating, and even intermittently iconic film.”

Rip Torn gets into a police car following a confrontation at an impromptu Jefferson Airplane concert in NYC as depicted in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1 PM (1971).

Other websites of interest:

https://phfilms.com/films/1-pm/

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/one-p-m-all-day

http://www.shockcinemamagazine.com/1pm.html

https://strublog.wordpress.com/2014/01/10/baraka-godard-and-the-lost-films-of-newark-1-pm-1972/

https://dangerousminds.net/comments/one_american_movie_jean_luc_godards_abandoned_sixties_manifesto

http://elshaw.tripod.com/jlg/One_AM.html

Pingback: Vitro Nasu » Blog Archive » RIP D. A Pennebaker a Pioneer Documentary Filmmaker

Pingback: The Origin of the Rooftop Concert: Before the Beatles Came Jefferson Airplane, and Before Them, Brazilian Singer Roberto Carlos (1967) – Fly Daily News