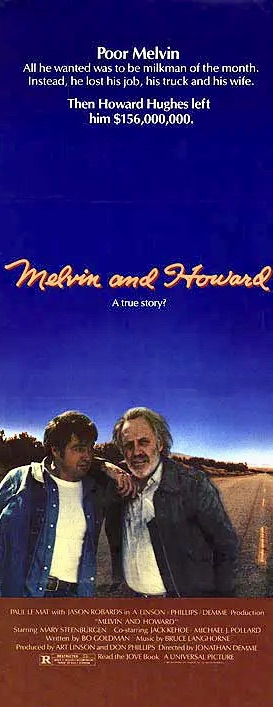

Over the years there have been numerous biographies written about aviation legend/studio mogul/eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes; everything from fake ones like Clifford Irving’s Autobiography of Howard Hughes to definitive accounts such as Howard Hughes: His Life and Madness by Donald L. Bartlett and James B. Steele. In contrast, there have been very few motion pictures about him. Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator (2004), based on the Bartlett & Steele biography, is the only feature film about his life to date. There was also a TV movie, The Amazing Howard Hughes (1977), with Tommy Lee Jones in the title role, and Jonathan Demme’s Melvin and Howard (1980), a quirky docudrama/comedy about Melvin E. Drummar (Paul Le Mat), a Utah man who claimed Hughes (Jason Robards Jr.) named him in his will after rescuing him in the Nevada desert.

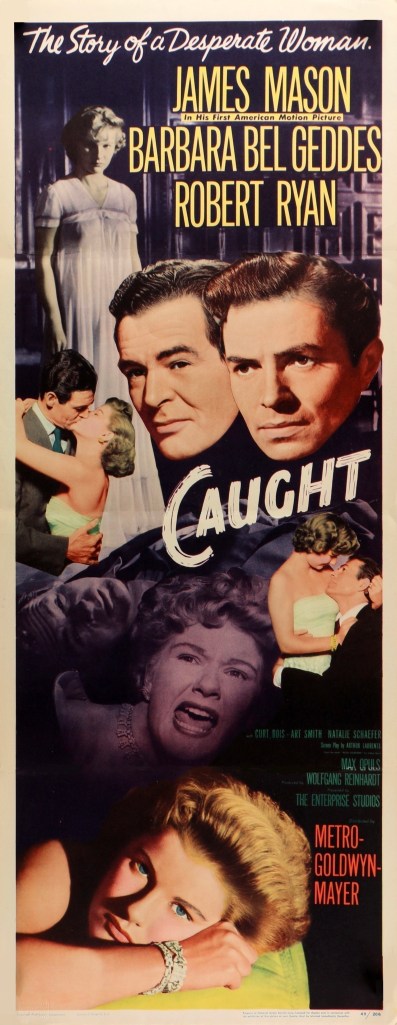

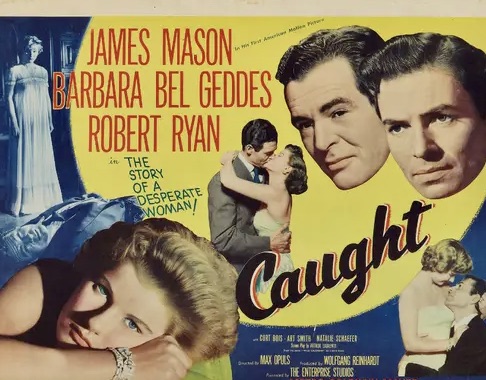

Strangely enough, my favorite film about Howard Hughes isn’t a biopic at all but a noir-like melodrama featuring a character who was clearly inspired by the megalomaniac tycoon – Caught (1949), by German director Max Ophuls. Smith Ohlrig, the business tycoon modeled on Hughes, may not resemble him in terms of a biographical profile but on a psychological level he is the epitome of Hughes in the way he interacted with women, his employees and industry rivals.

Initially, the project was planned as a debut feature for the independent production company Enterprise Productions, Inc., using Libbie Block’s 1946 novel Wild Calendar as the source material. Ginger Rogers was originally slated to play the female lead and several noted screenwriters such as Kathryn Scola, Abraham Polonsky and Paul Jarrico all tried their hand at penning a workable script. By the time, Max Ophuls was assigned to direct it, Paul Trivers was the screenwriter but one of the producers ended up tossing out the Trivers adaptation and hiring Broadway playwright Arthur Laurents to create a new screenplay.

Block’s original novel focused on Maud, a young woman from Denver, who ends up marrying a successful businessman, who has an unusually close relationship with his brother. The marriage is a disaster and Maud eventually divorces Smith Ohlrig and marries hotel manager Sonny Quinada. Yet, Maud continues to keep in touch with her ex-husband and secretly accepts money from him to buy a hotel for herself and Sonny to run. When Sonny finds out, their relationship falls apart temporarily and he goes off to fight fascism in Europe (The novel is set during WW2).

By the time Ophuls and Laurents collaborated on it, Block’s story had been severely altered with numerous characters and subplots dropped from the original narrative. In the final version, Maud becomes Leonora, a car hop waitress with a gold-digging roommate named Maxine. Determined to get a better job, Leonora budgets her meager salary so she can attend Dorothy Dale’s charm school. Upon graduating, she manages to get a better paid job modeling fur coats at a department store. One day, a suspicious man with an accent named Franzi Kartos invites her to a private party on a yacht owned by business tycoon Smith Ohlrig. She doesn’t have any desire to go until Maxine convinces her not to ignore what could be a golden opportunity.

In an unexpected turn of events, Leonora meets Smith Ohlrig at the dock while waiting for a ride to the yacht. He convinces her to join him while he conducts some business in the city and then takes her to his mansion for a drink. Although she is charmed by him and impressed with his affluent lifestyle, she refuses his advances and he takes her home. Leonora’s refusal to behave the way Smith Ohlrig expected triggers confusion in the tycoon and he consults his psychiatrist about it. The two men argue about Ohlrig’s belief that all women are after his money and nothing else. “Whenever I can’t get what I want, I have an attack. Is that your theory?,” the patient says to his doctor. As if to prove to the psychiatrist that he isn’t afraid of getting married, Smith Ohlrig rushes into matrimony and Leonora is soon leading a life of luxury in the millionaire’s East Coast residence on Long Island.

Unfortunately, Leonora rarely sees her husband between his constant travel and business meetings and, when she does, he treats her like a servant, expecting her to obey every command. The isolation and loneliness drive her to a desperate state and she begs Smith Ohlrig to let her go. Refusing to take his money, she finds a job as a receptionist at a doctor’s office in a poor neighborhood in the city. Over time she learns new skills and becomes confident in her work and Dr. Quinada, her employer, finds himself falling in love with her. Complications arise when the doctor proposes marriage to Leonora. Smith Ohlrig has been secretly tracking her in the city and re-appears at her apartment, pleading with her to give him another chance. Leonora gives in to her estranged husband but her troubles are just beginning.

Although Leonora (aka Maud) was the central focus of Block’s original story, Laurents and Ophuls give Smith Ohlrig and Dr. Quinada equal representation in Caught, with the former often threatening to dominate the story. In fact, Laurents integrated some of Ophuls’ own experiences of first working with Howard Hughes during his arrival in Hollywood in 1946.

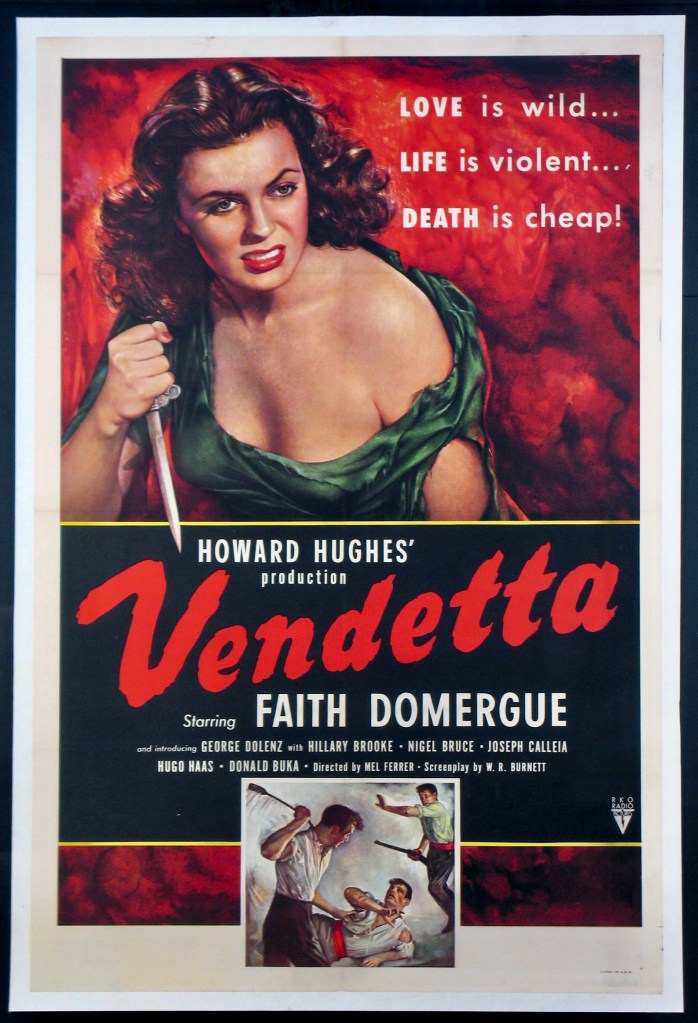

Ophuls was originally hired to direct Vendetta, a florid melodrama starring Faith Domergue, Hughes’s newest protégé. The director worked on Vendetta for eleven weeks – it was supposed to be his American film debut – before being fired by Hughes for his slow shooting process and his direction of the fledging actress (it was only her third film and she had the starring role). Hughes also disliked working with “foreigners” and he referred to Ophuls as “the oaf.” The film went through other uncredited directors such as Stuart Heisler and Preston Sturges before Mel Ferrer was brought in to complete the picture. As a result, Vendetta wasn’t released until 1950 but Ophuls’ experience of working with Hughes was such a nightmare for him that the Smith Ohlrig character in Caught became an avatar for the infamous mogul.

Caught is the most underrated of Ophuls’ four Hollywood productions – which includes The Exile (1947), Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948) and The Reckless Moment (1949) – but I find it a fascinating hybrid of soap opera and film noir. In fact, some admirers refer to it as a “noir romance.” All of the typical Ophuls’ trademarks are on display here – elaborate camera movements, lavish settings with elegant décor (juxtaposed against shabby working-class settings in this case), the use of musical motifs and a strong female protagonist. As film scholar Richard Roud once wrote, “What are Ophuls’s subjects? The simplest answer is: women. More specifically, women in love. Most often, women who are unhappily in love, or to whom love brings misfortune of one kind or another.”

It is interesting to note that when Enterprise Productions Inc. began finalizing the cast for Caught, both Barbara Bel Geddes and Robert Ryan were contract players at RKO, Howard Hughes’s studio. The mogul was well aware that Ophuls was basing the Smith Ohlrig character on his former boss but he didn’t interfere with or try to stop production. His only stipulation was that the tycoon not have a Texas background or be dressed in rumpled clothes (which was how Hughes usually looked in photographs).

Barbara Bel Geddes is an inspired casting choice as Leonora and is consistently convincing as a somewhat naïve working class girl with a strong moral compass. Yet she is completely overwhelmed by having to navigate a relationship with an emotionally volatile and manipulative partner. As her situation becomes more claustrophobic and confining, Ophuls accents the ominous mood with distinctively framed compositions that place Bel Geddes at the corner of the screen while Robert Ryan dominates the background, foreground or moves threateningly into the center.

In a role that was originally planned for Kirk Douglas, Ryan is magnificent as the malevolent, emotionally damaged husband. Some critics think his Smith Ohlrig character is in the same vein as his anti-semitic sociopath in Crossfire (1947) or his revenge-obsessed vet in Act of Violence (1948) but Ryan also manages to invest his tyrannical tycoon with vulnerability and a paralyzing self-pity. Notice his strangled voice and facial expressions as well as his body movements during his first big freakout scene in Caught where he frantically tries to take his panic pills before he collapses. The performance looks heavily influenced by the method school of acting, which hadn’t yet erupted on the screen until 1951 with the release of A Place of the Sun (Montgomery Clift) and A Streetcar Named Desire (Marlon Brando). But Ryan was never a proponent of ‘The Method,’ even though he had worked with Lee Strasberg on Broadway in a production of Clifford Odets’ Clash by Night in 1941. Ryan later admitted in an interview at UCLA that he consulted with Howard Hughes on his performance in Caught: “Howard knew all about it and even encouraged me to ‘play him like a son of a bitch.'”

As for James Mason in the role of Dr. Quinada, he was anxious to escape the dark, handsome brute stereotype that had made him a matinee idol in the U.K. in such films as The Man in Gray (1943) and Man of Evil aka Fanny by Gaslight (1944). He is certainly dashing and charismatic as the idealistic physician in Caught and is clearly the polar opposite of the maniacal Smith Ohlrig but the role feels underdeveloped. However, Mason would soon appear in a film that would more fully utilize his acting skills – as a seductive blackmailer in Max Ophuls’ 1949 noir The Reckless Moment opposite Joan Bennett.

In addition to the superb trio of Bel Geddes, Ryan and Mason are some vivid supporting performances from Curt Bois as Smith Ohlrig’s obsequious assistant/punching bag, Frank Ferguson as Quinada’s kindly, downhome fellow physician, Art Smith as a shrewd, observant psychiatrist and Ruth Brady as Leonora’s unsentimental, hard-nosed roommate.

Certainly, there are some problems with Caught, especially the ending which seems rushed – the result of some last minute meddling. It’s true there were plenty of problems behind the scenes such as Ophuls being fired as the director and being replaced by John Berry and then being brought back to finish Caught after Berry was fired. So, in a sense, the film is not completely Ophuls’ work and at least a third of Berry’s contributions remain. Nevertheless, Caught feels like an Ophuls film through and through and its reputation has improved considerably since its release in 1949 when it proved to be a critical and commercial failure.

David Thomson in his film reference work, “Have You Seen…?”, wrote, “Caught is a treat. Somehow all the mixed motives have conspired to make a love story noir in which the rawness of the material makes a rich contrast with the sophistication and warmth in Ophuls’s way of looking at people.” And Charles Taylor in his review for Salon stated, “It’s a coruscating portrait of American fantasies and the confines of class. Visually (the movie was shot by Lee Garmes) Caught is a succession of private traps. The sets are either cramped and dingy, like Leonora’s apartment and the doctor’s offices where she works, or, like Ohlrig’s mansion, so cavernous they seem unable to sustain human life. Still, the movie chooses the fetid air of the tenements where Leonora and her doctor work, over the stultified air of Ohlrig’s mansion. For Ophuls it’s an easy, unsentimental choice. He escaped the clutches of a crazy millionaire, too. He appears to have caught a whiff of genuine madness during his time with Hughes. This bitter little movie was Ophuls’ way of making sure he never forgot it.”

Of course, Ophuls would go on to make some of his greatest films following Caught such as Letter from an Unknown Woman. Most critics, however, rank his final four films that he made in Europe as his essential masterpieces – La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1952), The Earrings of Madame De…(1953), which was ranked at number 90 in Sight and Sound’s 2022 critics’ poll of the top 100 movies of all time, and Lola Montes (1955).

From Ophuls’ Hollywood period though, I still have an abiding fondness for Caught and will conclude with this quote from an interview in Wide Angle with the great Lee Garmes (Shanghai Express, Nightmare Alley), the cinematographer on the film: “Without a doubt, I think Max Ophuls was one of the greatest filmmakers we had…A sweet, sweet man, he got a very raw deal in Hollywood. But if you look at Caught you’ll feel that the camera was looking through a crack of a window or a crack of a door, or that the camera was never placed in a spot in the whole picture that was conventional, like most directors do.”

Caught was released as a multi-format offering (Blu-ray & DVD) from Olive Films in July 2014. It was a no-frills release (no extras) and is now out of print but you can still find copies for sale from online distributors.

Other links of interest:

https://www.theyshootpictures.com/ophulsmax.htm

https://www.hollywoodsgoldenage.com/actors/bel-geddes.html

https://theasc.com/articles/caught-a-lost-noir-classic