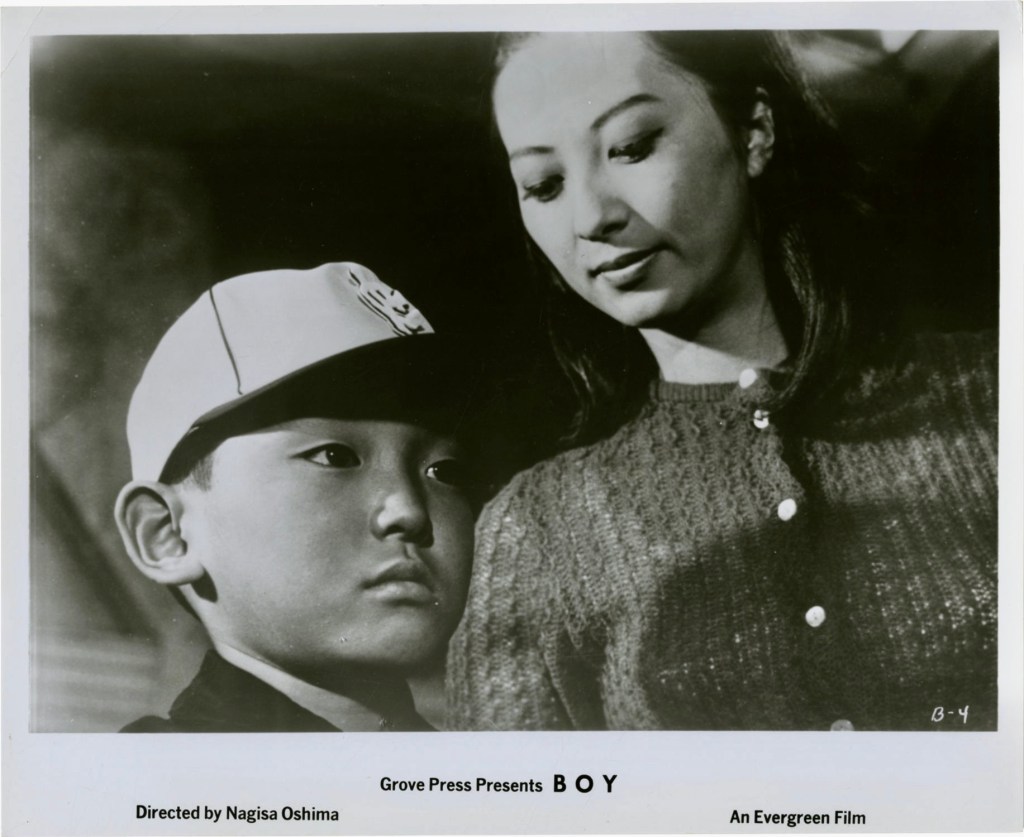

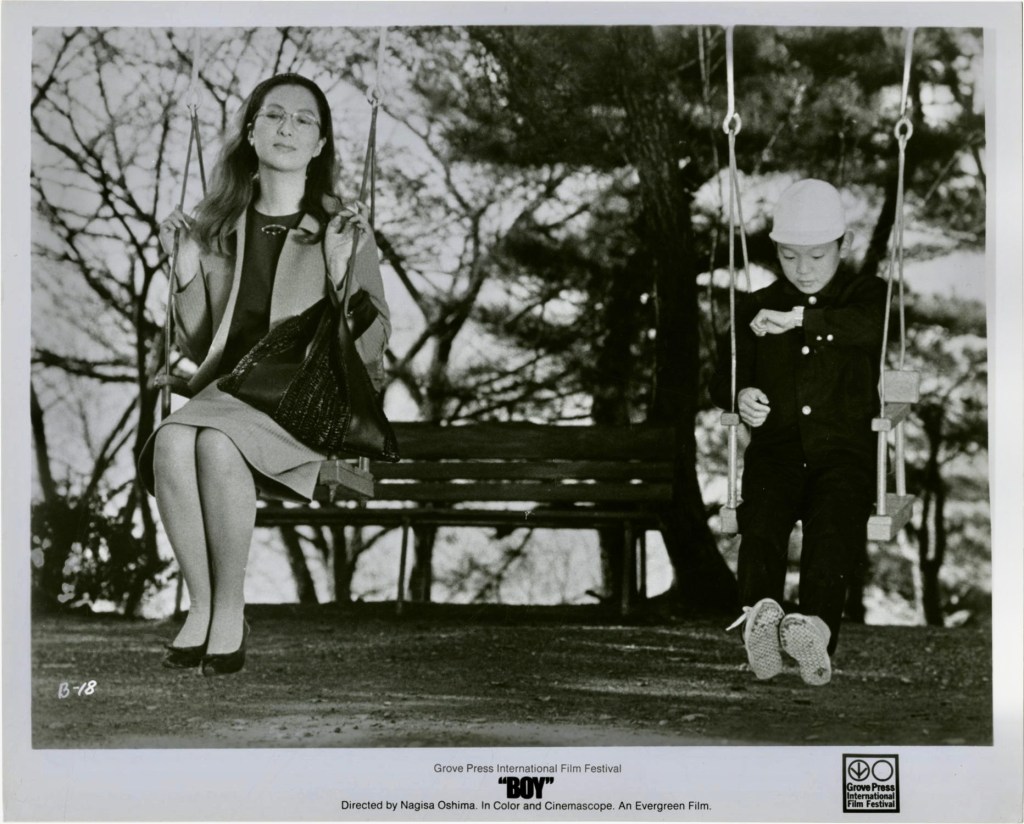

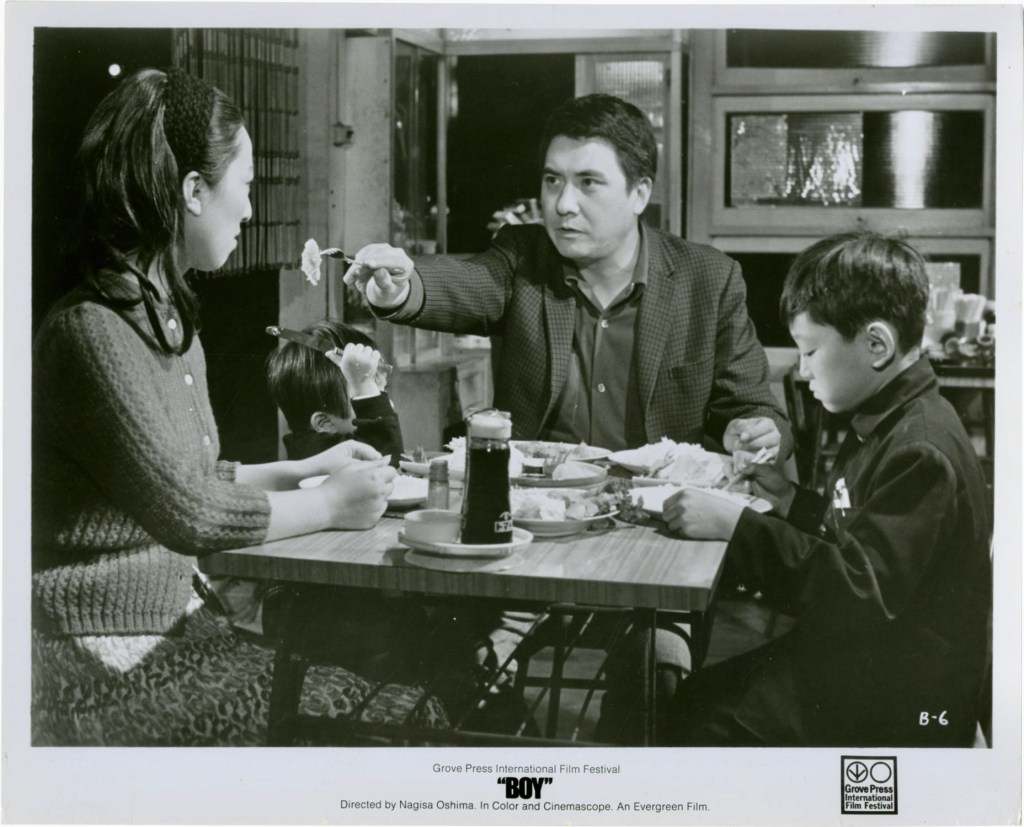

Not everyone has an idyllic childhood and some unfortunates don’t even have a childhood at all. That is certainly the case with Toshio (Tetsuo Abe), a ten-year-old who is being used by his father Takeo (Fumio Watanabe) and stepmother Takeko (Akiko Koyama) in an ongoing scam which entraps car drivers. The ploy involves stepping out into traffic, pretending to be hit by a car, and falling to the ground and feigning an injury. If the driver doesn’t offer to settle the incident on the spot with a cash payment, the fake victim threatens to call the police to settle the matter. In many cases, the drivers are only too happy to pay the scammers a cash settlement to avoid a lawsuit or court case. Toshio and his family of three (including a tiny tot named Peewee) have been on the move across Japan, enacting this scenario for some time with Takeko playing the fake accident victim. But the time has come for the parents’ ten-year-old to take on this role and he has little choice in the matter. So begins Nagisa Oshima’s Shonen (English title: Boy, 1969), a harrowing portrait of parental abuse and negligence, which was based on a true case that made national news in Japan in 1966.

Toshio (who is rarely addressed by his name throughout the film) lives a completely isolated existence. Since his family is always on the move with their money hustle, he is unable to attend school or develop any friendships. As a result, he often retreats into a fantasy world where he pretends to be an alien who has come to earth to punish evildoers. Yet, even though he is only ten, he also has no illusions about the real world and realizes his sole function in the family is to serve his parents’ materialistic schemes. What do they offer in return? An occasional meal and some questionable advice on who to pick or avoid as money targets. “No taxis or fast drivers. Just station wagons or compacts with company logos. Women drivers are best.”

As he moves into his new role as slave laborer, Toshio learns there are considerable perils with his new job. Not only does he risk genuine injuries from his car tagging but he also has to constantly lie to the police and doctors who examine him (His father even injects him with a substance which makes his skin look bruised and discolored). Worst of all is the possibility that their con game will be exposed and his parents will go to jail while he and Peewee will be sent to an orphanage. As miserable as his life is, Toshio still prefers being part of a family unit to being alone because it is the only social structure he has ever known. But how long can the family continue this criminal charade they are playing?

Boy is often considered one of Oshima’s most accessible and straightforward films but it never lapses into blatant sentimentality or pathos. Nor does the director try to manipulate viewers’ emotions through music cues or dramatic provocations. The entire narrative reflects a dispassionate, observational viewpoint not unlike a documentary on a specific social problem. As abhorrent as the parents are in Boy, they are victims of a broken childhood as well. Takeo lost his own father at age five and drifted into juvenile delinquency as a teenager while Takeko was virtually abandoned by a mom with four failed marriages. The family these two adults create in Boy is like a horrible parody of the traditional patriarchal structure in Japanese families. There is no group harmony or respect for anything except material needs and a dog-eat-dog attitude prevails in every situation.

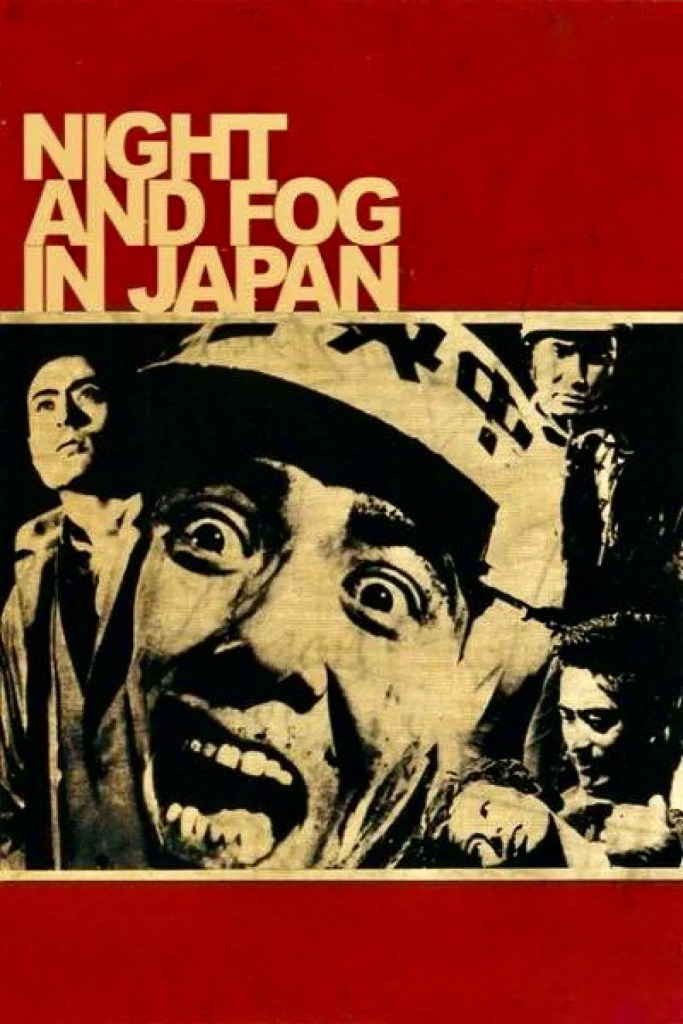

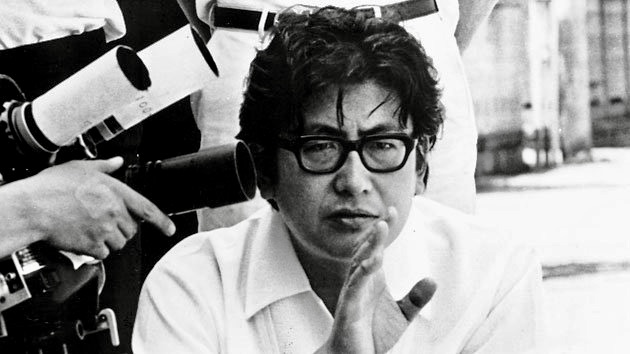

Oshima established his credentials as a radical filmmaker from his earliest films such as A Town of Love and Hope (1959) and Cruel Story of Youth (1960), both of which examine class differences and social misfits in post-war Japan. The director was particularly interested in exploring Japan’s national identity and how that had changed after they lost the war. Imperialism, death, sex and leftist politics were always topics he addressed in his films but this was problematic for a commercial movie studio like Shochiku where Oshima launched his career. The director eventually went independent in 1960 when the studio pulled his political drama Night and Fog in Japan from theaters after three days due to the assassination of the leader of Japan’s Socialist Party by a right-wing nationalist.

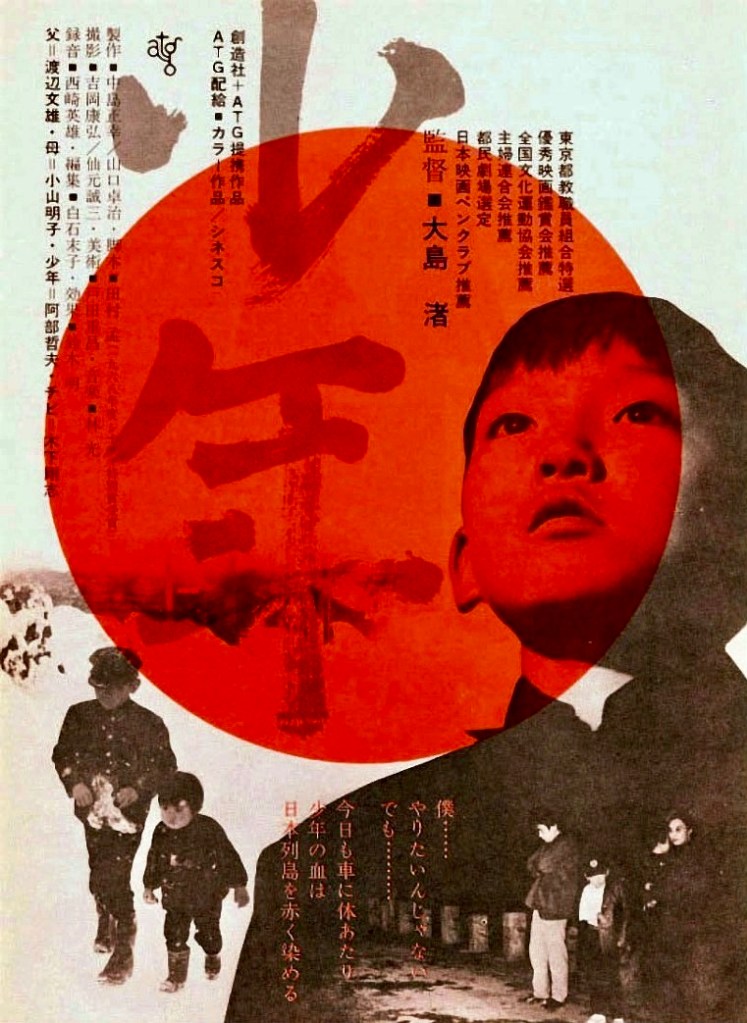

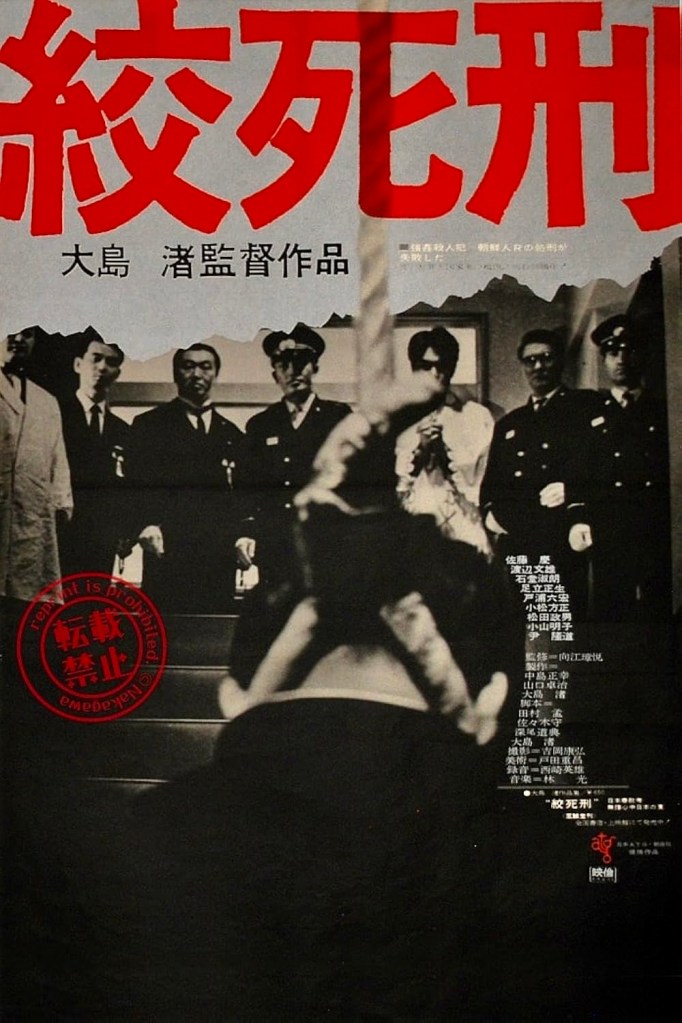

Setting up his own production company, which he named Sozosha, Oshima made films on his own terms which still seem provocative and uncompromising today like Violence at Noon (1966) and Double Suicide: Japanese Summer (1967). In 1968, he partnered with Art Theatre Guild (ATG) to make one of his greatest movies, the macabre satire Death by Hanging, and he would turn to ATG again when he needed to raise funding for Boy.

The idea for the film was inspired by the real-life criminal family that made headlines in 1966 and Oshima put together a production team just ten days after he read the news story. Still, it would take him two years to actually start filming from a screenplay written by his longtime filmmaking partner Tamura Tsutomu.

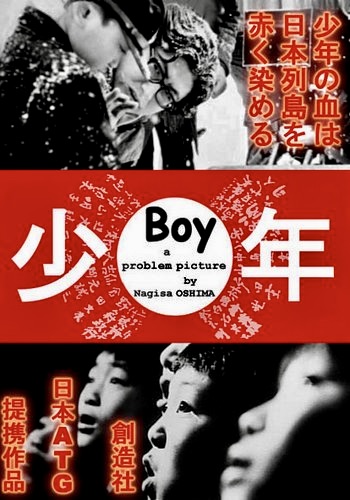

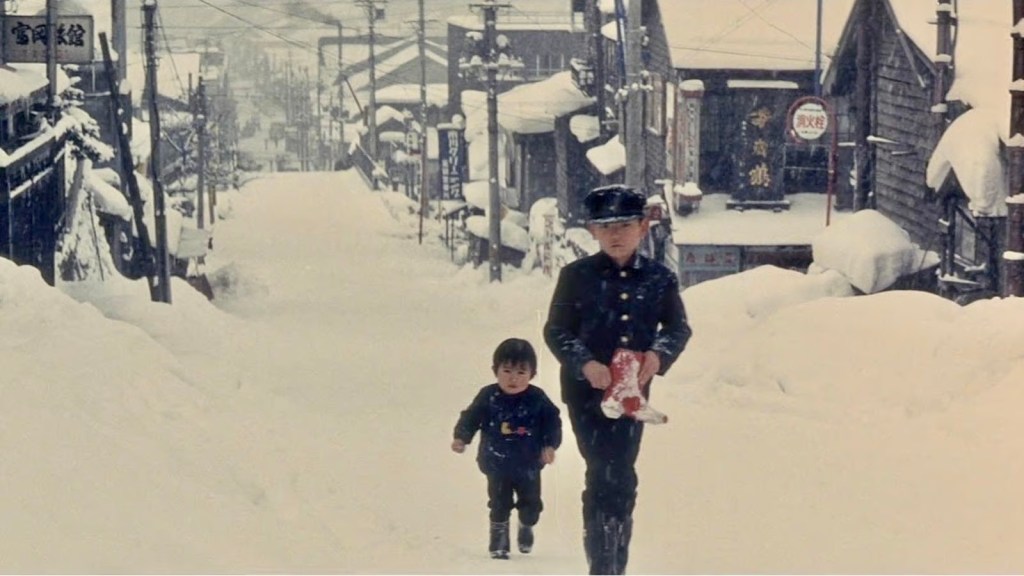

Boy was ATG’s first color film and it was filmed all over Japan in order to replicate the fugitive family’s original flight from justice. Fumio Watanabe, who appeared in many of Oshima’s films, is perfectly cast as the greedy, bullying father and Akiko Koyama, the director’s real-life wife, plays the passive/aggressive stepmom in a balancing act that generates both pity and disgust. At the time Oshima made Boy, he was working more with non-professional actors than established stars and, for the title character, he interviewed numerous orphans in Tokyo’s children’s home before selecting Tetsuo Abe, whose own life had been as unstable as the child he would soon play. Abe developed a warm working relationship with the entire film crew and, according to Oshima, a few of them even offered to adopt him. Despite this, the young actor opted to return to the orphanage after shooting because his own experience with foster homes was negative and he wanted no part of it.

Boy was a critical and commercial success in Japan and garnered international acclaim as well but its reception was mixed in the U.S. For example, Howard Thompson of The New York Times wrote, “This simplest of stories unwinds deviously, dankly, pretentiously and endlessly, as seen through the eyes of the boy, aging before our eyes…Nagisa Oshima…substitutes nagging irony and a curious, sophisticated detachment of style and tone for real compassion.”

In recent years, the film has been reassessed as an overlooked masterpiece. Tom Milne of The Observer calls it “weird, beautiful and terrifying” and Don Drucker of The Chicago Reader wrote, “Oshima, the Japanese filmmaker most often compared with Godard, treats the material in a matter-of-fact manner that serves to heighten the dramatic impact and to create one of the most interesting films about children ever made.” David Thomson also highlighted the film in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: “Oshima has shown a taste for dramatic human stories that are metaphors of the recent history of Japan. Boy, an extraordinary account of a wandering family that fake road accidents for insurance settlements, as well as having great narrative interest, is a portrait of the moral confrontations forced upon the new Japan.”

Boy remains fresh and innovative after more than fifty years and part of that is due to Oshima’s use of atonal music (the score is by Hikaru Hayashi), a switch between black and white and color cinematography to emphasize certain events, the use of still photographs and unusual framing that often places the child protagonist on the edges of the compositions, isolated but also easily overlooked in the big picture. Certainly, Tetsuo Abe’s quiet, blank faced cipher is a haunting presence and, when he occasionally erupts in an emotional outburst under duress, it is especially jarring and unexpected (Sadly, this would be his only film).

Among the many scenes that stand out are Toshio building an alien snowman for his brother Peewee and his stunned reaction to a traffic accident caused by his family standing in the middle of an icy road. A female driver swerves to avoid hitting them and crashes into a telephone pole. Toshio watches as her lifeless body is carted off by an ambulance but one of her red snow boots remains left behind in the snow. This image will come back to taunt the boy when his family is finally apprehended by the police. There is also a turbulent confrontation scene when Takeo discovers his pregnant wife has refused to get the abortion he ordered and he attacks her viciously while his son tries to protect her.

In later years, Oshima would become an even more controversial director with the release of the sexually explicit drama, In the Realm of the Senses (1976), which is still banned in Japan in its uncensored version, and the erotic ghost story, Empire of Passion (1978) but Boy is an excellent introduction to his work for beginners.

It is true that a large portion of Oshima’s filmography is available on DVD or Blu-ray in the U.S., but Boy has remained difficult to see on any format. It has turned up in retrospective screenings at film festivals and it recently aired on Turner Classic Movies but it will soon be widely available on Blu-ray, thanks to Radiance Films. On November 17, 2025, they are releasing Radical Japan: Cinema and State, a 7-disc set of nine Nagisa Oshima films that includes Boy, The Ceremony, Diary of a Shinjuku Thief and The Catch, among others. This is an all-region release so it will play on any U.S. Blu-ray player and it comes with a host of extra features.

Other links of interest:

https://www.artforum.com/columns/nagisa-oshima-216428/

https://www.shitsurae-japan.com/p/nagisa-oshima-and-boy?utm_medium=web