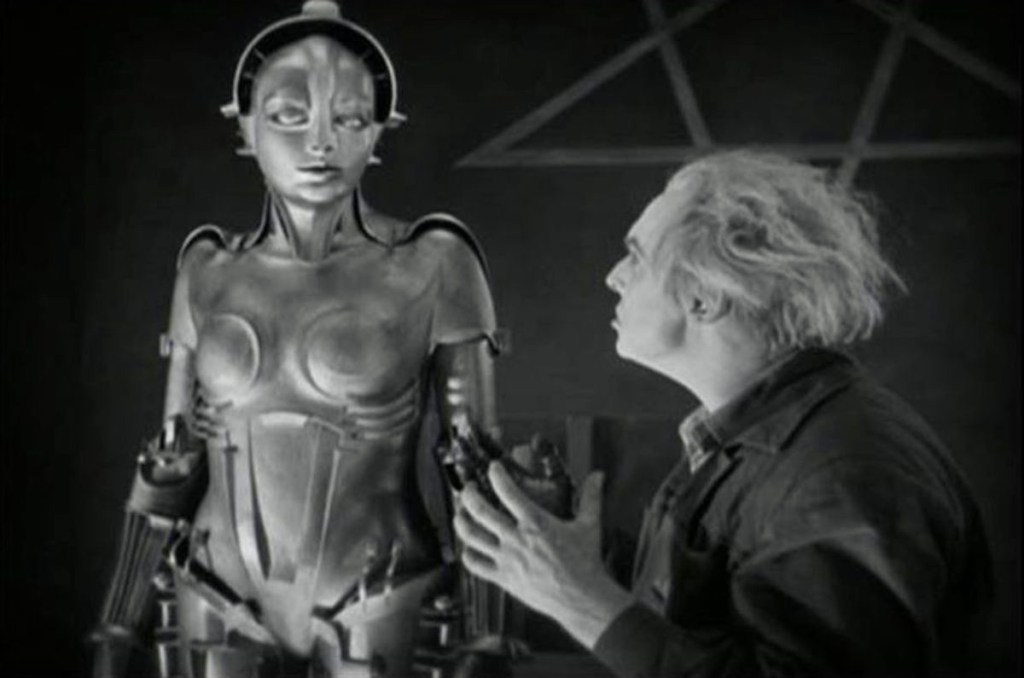

When I hear the word robot, I immediately think of Robby, the delightful and super intelligent creation of Dr. Morbius in Forbidden Planet (1956), one of the landmark sci-fi movies of the fifties. His barrel-shaped torso and high-tech design were so popular that he inspired countless toy collectibles for kids but he was a benign example of the form. For the most part, robots in science fiction films are generally viewed as a threat (see 1954’s Target Earth, 1957’s Kronos or 1958’s The Colossus of New York for examples). That was certainly the case in one of the first and most famous depictions of a robot – Fritz Lang’s silent sci-fi masterpiece, Metropolis (1927). Designed as a doppelganger for Maria, a revered female leader of factory workers, the false Maria preaches revolution to the working class, resulting in the sort of chaos that threatens to topple civilization (The False Maria’s robotic metal frame is disguised beneath her human façade).

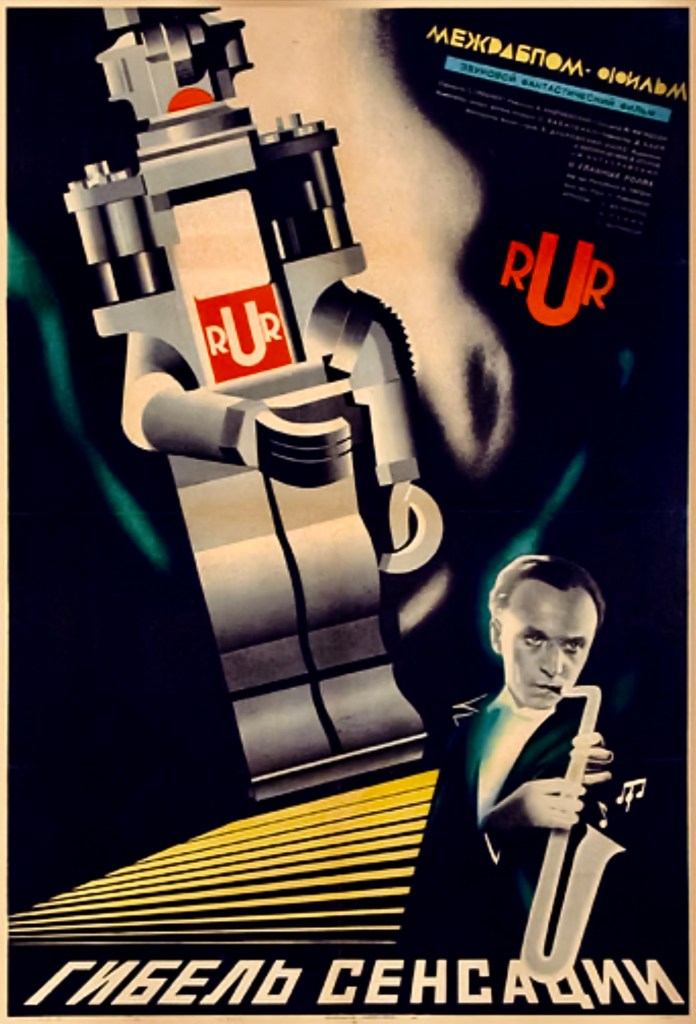

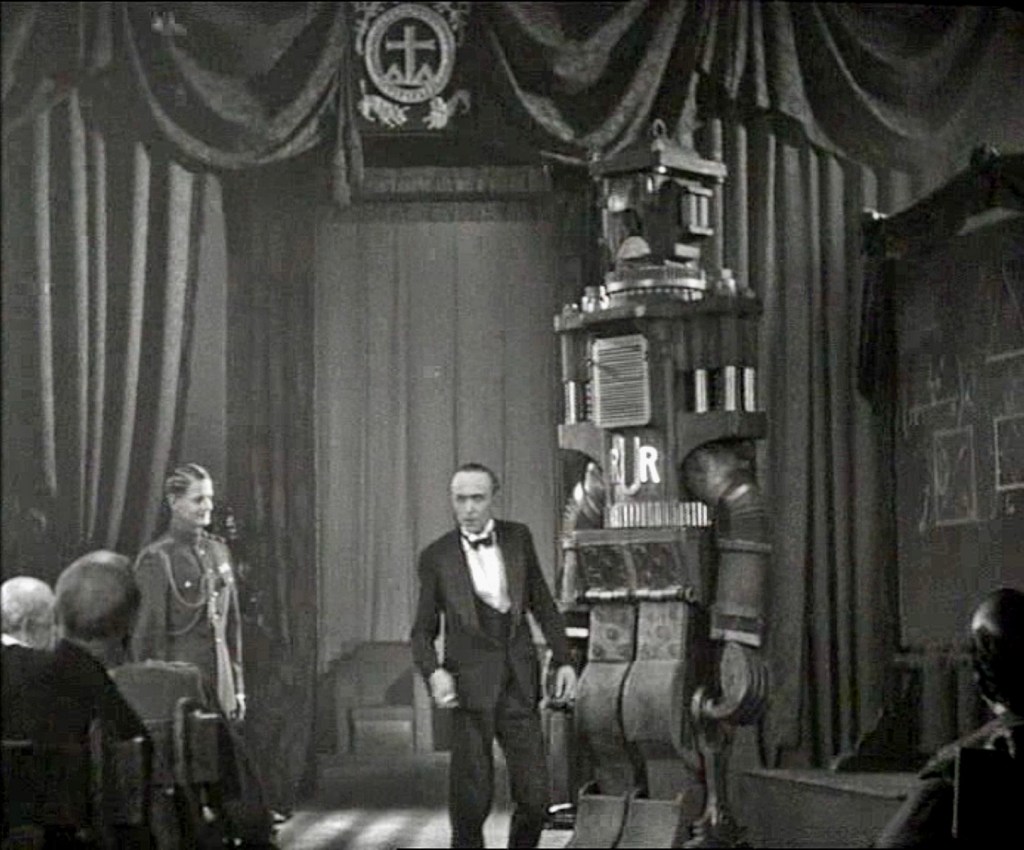

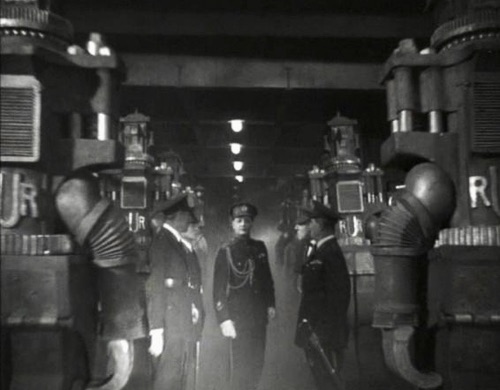

Eight years later, robots were again viewed as a danger to the human race in the Russian film, Gibel Sensatsii (English title: Loss of Feeling aka Loss of Sensation aka Robots of Ripl, 1935) although these looked more like early prototypes of the walking oil can-shaped automatons seen in later serials like The Phantom Empire (1936) and The Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940).

Directed by Aleksandr Andriyevsky, Loss of Feeling is a lesser known effort that lacks the epic scale and technical virtuosity of Metropolis but it is still well worth seeing for sci-fi buffs for its view of mechanized man-made machines and how they could both aid and harm human life.

Although some sources claim that Loss of Feeling is based on the 1920 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) by Czech writer Karel Capek (who helped popularize the word ‘robot’), Andriyevsky’s debut feature is actually inspired by the 1929 novella Idut Robotari! (aka Forward, Robots!) by Volodymyr Vladko, the Ukrainian science fiction author who was often compared to Jules Verne.

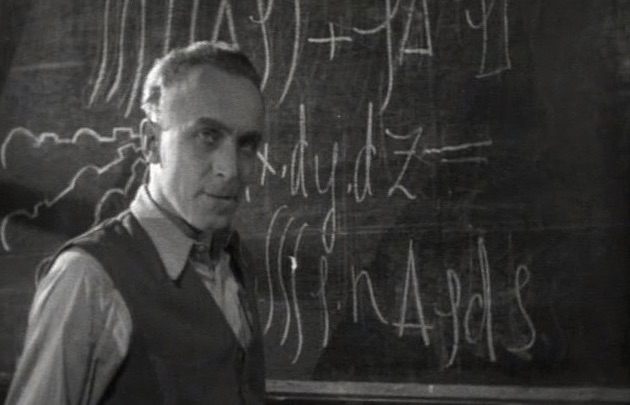

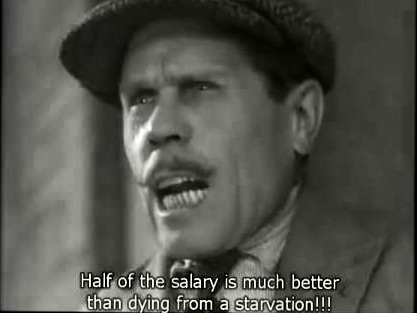

Set in an unspecified capitalist country (which bears similarities to both America and Germany), Loss of Feeling is as much of a propaganda vehicle as it is a science fiction cautionary tale. At the center of the story is Jim Ripl (or Ripley in some versions), played by Sergei Vecheslov. He is an idealistic engineer who is recruited for a top secret government study of mechanization in the work place. He quickly sees that the capitalist leaders of his country are forcing the proletariat workers at factories to work faster but for reduced wages in an effort to be more profitable.

Jim comes up with a solution but his true intention is to undermine the establishment. “I have created an automatic device which can do anything,” he tells his brother Jack (Vladimir Gardin) and family members when introducing them to Micron, his robotic worker. “He will easily replace all the workers on any factory. What will happen? The world market will be overfilled. The prices will decrease. And without any revolution, the capitol itself will not exist any longer.”

Unfortunately, a demonstration of Micron’s abilities only confirms Frank’s fears about his brother’s creation and he denounces Jim as a traitor who favors the capitalists over the working man. Frank then angrily destroys Micron and Jim is banished from the family although his sister Clare (Mariya Volgina) remains loyal.

Misunderstood and disillusioned, Jim decides to join forces with fellow engineer/evil capitalist Hamilton Grimm (Vergiliy Renin) and comes up with a solution for the “proletariat problem” – a bigger, more versatile version of Micron called RUR (the name is borrowed without credit from Capek’s 1920 play of the same name hence the confusion over the movie’s source material).

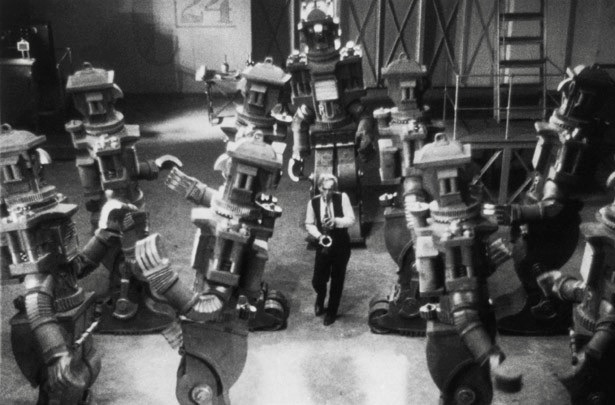

Jim’s army of RURs are trained to follow his commands through his musical signals on a saxophone! In one of the craziest sequences, the robots surround him and dance, swinging their arms and legs in unison. But Jim soon loses control of his creations and Hamilton and his capitalist backers commandeer the RUR army for their own purposes. When the out of work factory employees threaten to revolt against their oppressors, Hamilton programs the robots to crush the revolt.

In the meantime, the proletariats, organized by Jack, find their own engineer who can figure out a way to stop or sabotage the RUR attack force by studying Jim’s original model of Micron. It all ends in a war between the workers and the capitalists with the rampaging robots creating massive destruction and death until their signals are reversed and they turn against their masters. [Spoiler alert] Jim, who is essentially the mad scientist of the piece, is trampled to death by his creations and Hamilton comes to a well deserved demise as he is pulled out of a tank by RURs and crushed by their metal hands.

Although much of Loss of Feeling is hampered by the blatant and heavy-handed anti-capitalist propaganda, there is enough imagination and bizarre bits of business on screen to keep the narrative engaging on a visual level. The nightclub sequences, in particular, that highlight the decadent lifestyles of the rich and powerful capitalists are quite stylish with Art Deco-inspired art direction and, in one scene, a lavish musical number performed by a Maurice Chevalier-like singer/dancer with a bevy of alluring chorus girls. In the midst of all of this is a mechanical doll seller (Aleksandra Khokhlova, actress/wife of Russian director Lev Kuleshov) who sells her creepy-looking figurines at the nightclub and Jim buys one, which leads to his creation of the new, improved RUR model.

The film also dispenses with any female love interest or romance to bog the story down (although the propaganda sermonizing doesn’t help). What is most interesting is that the true hero of the film is Roy, a proletariat engineer, who is identified as a black man along with several supporters (these men of color are shown to be a mix of black, Asian, Indian and other nationalities). While it might at first seem racist, the skin reference is meant to demonstrate Roy and his dark skin friends’ unification with the working class.

Of course, the real stars of Loss of Feeling are Micron, who performs wonders on a sewing machine and can shuttle back and forth at high speeds, and the oversized RUR creations who resemble some kind of steampunk contraption. The special effects may be occasionally crude but they are always amusing and consistently fun to watch, even when the action becomes repetitive. Another plus is the jazz-influenced music score by Sergei Vasilenko and the dense sound design, particularly in the climatic robot attacks where the sound of exploding bombs and mechanical machine noises reach a crescendo.

Some of the art direction is equally impressive such as the early scenes set in a factory where workers are encased within the revolving numbered spheres of assembly line production, spinning faster and faster. And certain camera shots and angles by cinematographer Mark Magidson create a sense of the fantastic with surrealistic flourishes.

On the minus side, there is very little character development in Loss of Feeling with the possible exception of Jim, who becomes an almost tragic figure by the end. The editing is also erratic and some scenes end abruptly or give one the feeling that something was deleted prior to release. Most sources list the running time as 85 minutes but perhaps there are longer versions of the film available?

Not much is known about director Aleksandr Andriyevsky who only directed a handful of features with Loss of Feeling marking his film debut. His other claim to fame is directing the first 3D version of Robinzon Kruzo aka Robinson Crusoe in 1947, which was a commercial hit in Russia.

Loss of Feeling is not well known today in the U.S. since it never had an official U.S. release and has never popped up on any legitimate DVD or Blu-ray release here. Video Dimensions has released a DVD with English subtitles but I can’t vouch for the quality. A German company Der Ostfilm offers a Blu-ray double feature of Loss of Feeling with the German silent film Cosmic Voyage (1936), complete with English subtitles, on a PAL import disc. You also might be able to stream a version of it with English subtitles on Youtube (which is where I saw a decent print of it).

Other links of interest:

https://www.berlinale.de/en/2012/topics/a-german-russian-film-experiment-retrospective-2012.html

http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/49760

https://www.rbth.com/arts/332630-russian-sci-fi-movies

https://www.artforum.com/columns/aleksandr-andriyevskys-robinzon-kruzo-199346/