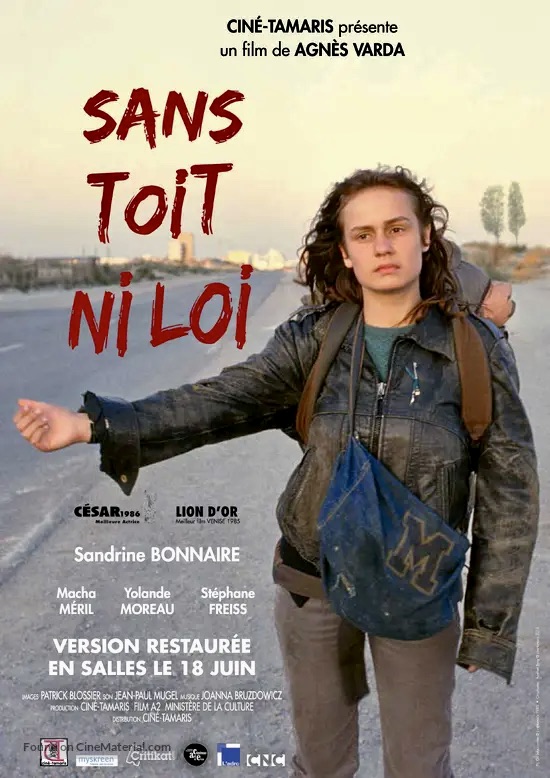

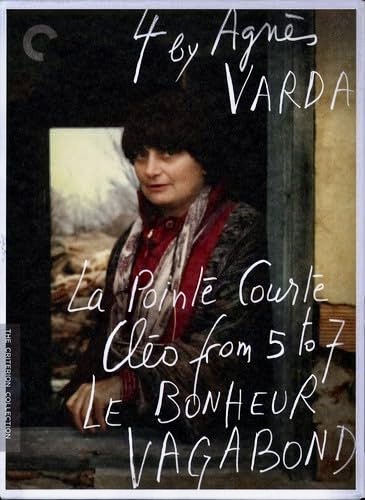

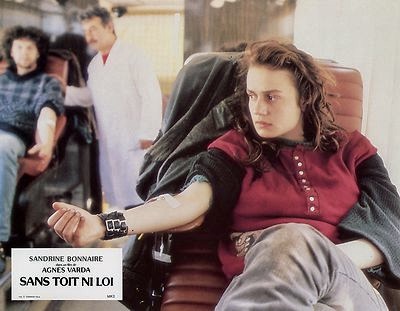

Film critics and moviegoers familiar with the work of French filmmaker Agnes Varda were unprepared for her seventh feature film Sans toit nil oi (English title: Vagabond) when it hit theaters in 1985. It had been eight years since her previous dramatic work One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977), an optimistic, semi-musical tale of female solidarity and friendship during the rise of the feminist movement in France, and her new feature couldn’t have been more different or unexpected. Nor did any of her earlier features – the New Wave influencer La Pointe Courte (955), Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), Le Bonheur (1965), Les Creatures (1966) or the experimental happening Lion’s Love (1969) – prepare viewers for the harsh realities and raw authenticity of Vagabond. Certainly the film was partially shaped by Varda’s own experience in documentary filmmaking but it also exerted a dramatic power and an almost visceral visual sense that was not apparent in the director’s previous dramatic work. Based on Varda’s encounter with a female vagrant, Vagabond focuses on the final weeks in the life of a homeless woman named Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire) who meets and interacts with various people along the roads of southern France before dying of exposure in a vineyard during a harsh winter.

That last line isn’t a spoiler because Vagabond opens with Mona’s stiff corpse being discovered by a laborer. Once the police are brought in to investigate the death, the movie becomes a post-mortem of a drifter, someone who was among the living one day and no more than a ghost or a memory the next. Varda takes us back to several weeks earlier in Mona’s life and we watch as this fiercely independent and polarizing individual navigates her way through the countryside with no clear indication of where she is going or what she wants.

Vagabond is structured in an episodic fashion where Mona’s journey on the road is interspersed with interviews of various people the girl encountered along the way and their impressions of her. Some of the interviewees even break the fourth wall and address the audience directly with their thoughts, which often tend to reveal more about themselves than Mona. We also learn bits and pieces about Mona’s past (she had previously worked as a secretary but quit because she hated taking orders) but never really learn what makes her tick.

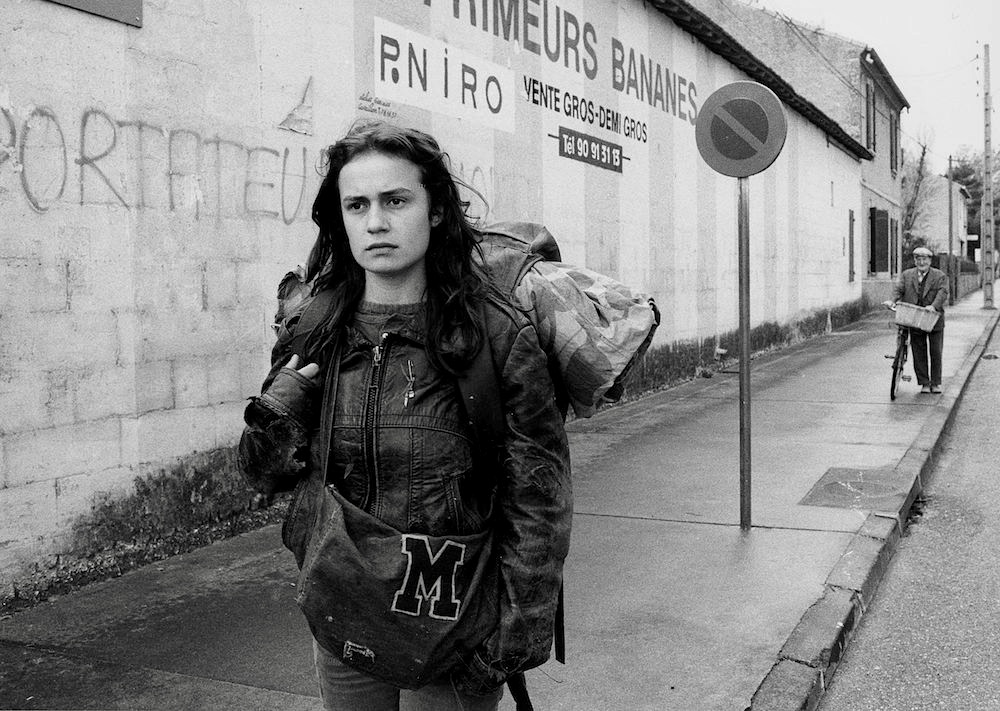

In some ways, Vagabond functions as an existential mystery thriller. Who was this woman and why did she die all alone? Yet, despite that grim premise, the film becomes a compelling exploration of human behavior and part of the fascination is due to Varda’s refusal to pass judgment on her protagonist. She leaves that for the viewer to decide and some may dismiss Mona because she is often selfish, insulting, destructive and aggressively anti-social with criminal tendencies. In addition, her stench and filthy appearance works as a defense against anyone who wants to get close or values cleanliness and good grooming as a sign of self-respect.

Clearly Mona’s defiant manner alienates some of those she meets but others envy her free-as-a-bird lifestyle or are fascinated by the choices she makes. Some of the dangers of the road are clearly on display – a male lurker in the woods attacks Mona (and the camera pans discreetly away as a rape probably takes place) – but Mona refuses to play the victim and occasionally hooks up with other drifters for food, sex, alcohol, drugs or shelter. Some of these encounters offer fleeting moments of joy and simple pleasures, others end disastrously such as a fire that breaks out in a vagrant’s hovel that destroys most of Mona’s few possessions (a tent and a sleeping bag) and invariably leads to her freezing to death.

In real life, most people would probably swing clear of someone like Mona but Vagabond affords us the opportunity to see her on her own and with others. She clearly doesn’t want or need sympathy and could care less about civilized society. She takes what she wants and never feels the need to say “thank you” for any favors rendered but Varda also shows us glimmers of the human being inside. In one scene we see Mona wake up in her tent and smile privately at her rural surroundings; in another she attempts to bond with the child of a goat herding couple. And we also see her delight at sharing brandy and conversation with an irreverent elderly woman (Marthe Jarnias, a non-professional actress who had appeared in Varda’s 1985 short 7p., s. de b….[a saisir]).

Still, the disturbing aspects of Vagabond are hard to ignore but the film is more than just a stark and unsentimental portrait of a homeless woman’s slide into oblivion. Varda dares to depict Mona as an independent free spirit, warts and all, and the viewer is left to decide whether she deserves her fate or to recognize her humanity.

Andrea Kleine in her essay on the film in The Paris Review pointed out “the film is so startling because its protagonist is a woman. We’ve seen male drifters and loners throughout film history. A man alone has a reason, and his isolation is therefore noble. In Manchester by the Sea, Casey Affleck’s character exiles himself as punishment for the accidental death of his children; in Ironweed, Jack Nicholson leaves home after dropping his infant son; Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas follows an amnesiac path trying to reunite his son with his mother, whose relationship he destroyed through abuse and neglect. A male drifter is doing penance for something for which he was found innocent but for which he cannot forgive himself. A woman alone is crazy. That she is not a sex worker makes her crazier.” But Mona is a special case. She rejects traditional life choices and takes her chances on the road.

The concept of Mona as an unlikely heroine had been germinating in Varda’s mind for some time. The director stated in an interview that, “It was in the 1980s that very young girls began to appear on the road and in doorways. They were not lost but had decided to live out their freedom in a wild and solitary way.” Vagabond is her eloquent illustration of this new found independence and its consequences.

Varda admitted that the movie was a DIY production in the best sense of the word. She wrote and directed it with a merger budget and a skeleton crew, traveling to the south of France and filming in the Gard, Herault and Bouches-du-Rhone regions during the winter months. “It really was a collective experience,” Varda stated in an interview. “Enduring the cold (without comfort trailers) – the mistral reached sixty miles per hour at times. Sharing a building that the city of Nimes lent to sports teams, who would come and play there, six rooms and two shower stalls per floor. Being outside practically all the time. And with real squats where we were filming, we had to forget our cleaning habits and the smells, and share what we could with those vagrants who occupied them.”

Varda also used mostly non-actors and local people to play themselves in the movie with only a few established actors in the cast such as Macha Meril (Godard’s The Married Woman, 1964) as Ms. Landier, an expert on tree diseases who offers Mona a ride. Other key roles include screen newcomers Yolande Moreau as an unhappy servant girl and Stephane Freiss as an assistant to Ms. Landier. But it is Sandrine Bonnaire’s fearless and almost feral-like performance as Mona that invests the film with her formidable presence and complexity. She was just 17 years old when she made Vagabond and had only appeared in a few bit parts and four feature films prior to this but the role propelled her to international fame overnight. She won the Best Actress prize at the Cesar Awards (France’s equivalent of the Oscars) and, in the U.S., received Best Actress nominations from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association (she won) and The National Society of Film Critics. Varda’s film also triumphed at the Venice Film Festival where Vagabond won the Golden Lion, FIPRESCI prize and the OCIC award for the director.

Vagabond also won universal acclaim from most movie critics with David Thomson, author of The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, writing “easily her most powerful film of recent years – and probably her best ever – is Vagabond, the tracking of a fierce, willful outcast, set more surely on a path to death than Cleo ever contemplated. Vagabond burns in the memory, lucid and unsentimental, like the challenging gaze of Sandrine Bonnaire.”

One of the critics who didn’t think Vagabond was some kind of masterpiece was The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael who called it “scrupulously hardheaded” and went on to say, “…we see the closed-off girl strictly from the outside, and this factual, objective view isn’t enough. Varda’s flat-out approach excludes the uses of the imagination – both hers and ours.”

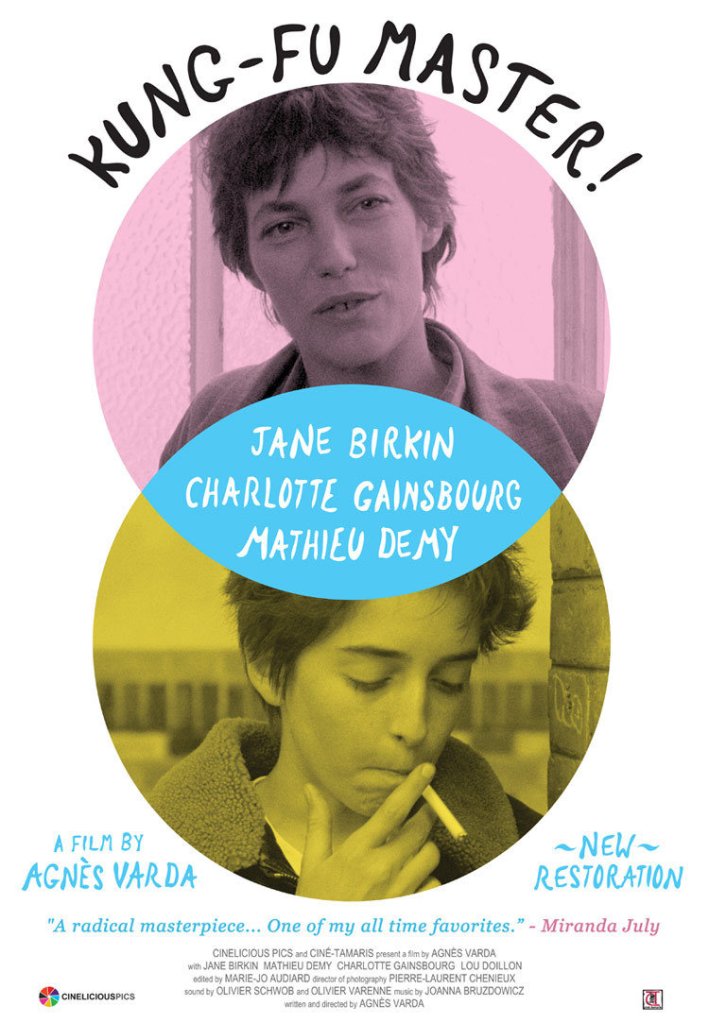

One thing is certain; Vagabond brought a renewed interest to Varda’s career and inspired her to pursue other personal projects for future features like Kung-Fu Master! (1988) starring Jane Birkin and her daughter, Charlotte Gainsbourg, and documentaries such as The Gleaners & I (2000) and The Beaches of Agnes (2008).

Unfortunately, Vagabond has still not been released on Blu-ray in the U.S. but admirers of the film might still be able to find and purchase it from online sellers as part of the DVD set 4 by Agnes, released by The Criterion Collection in January 2008 (it is now out of print). The set also includes La Pointe Courte, Cleo from 5 to 9, Le Bonheur and a wealth of supplemental features.

Other links of interest:

https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/travel-france-agnes-varda-filmography/

https://www.interviewmagazine.com/film/agnes-varda

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/501-vagabond-freedom-and-dirt

https://filmstarpostcards.blogspot.com/2017/09/sandrine-bonnaire.html