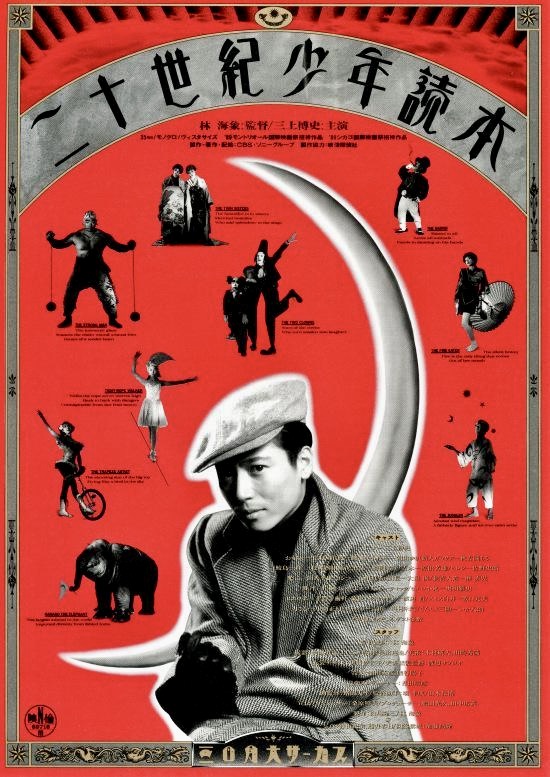

When was the last time you went to the circus? For most people, that form of popular entertainment has changed drastically over the years and is now more likely to be a showcase for human acts like Cirque de Soleil than one featuring performing animals (dancing elephants, lion taming, horses leaping through hoops of fire, etc). But there was a time from the late 19th to the middle of the 20th century when circuses were the ultimate family entertainment. Movies, in particular, captured the golden age of the circus in a variety of genres that ranged from big screen spectacles (The Greatest Show on Earth [1952], Circus World [1964]) to slapstick comedies (The Circus [1928], At the Circus [1939]) to Walt Disney fare (Dumbo [1941], Toby Tyler or Ten Weeks with a Circus [1960]) to horrific murder mysteries (Circus of Horrors [1960, Berserk [1967]). Yet, there are few, if any, that merge fantasy and reality in the style of Japanese director Kaizo Hayashi’s Nijisseiki Shonen Dokuhon (English title: Circus Boys, 1989). This balancing act is also matched metaphorically through the two main protagonists who must learn to come to terms with gravity, whether it is riding an elephant, walking a tightrope or finding stability in their lives.

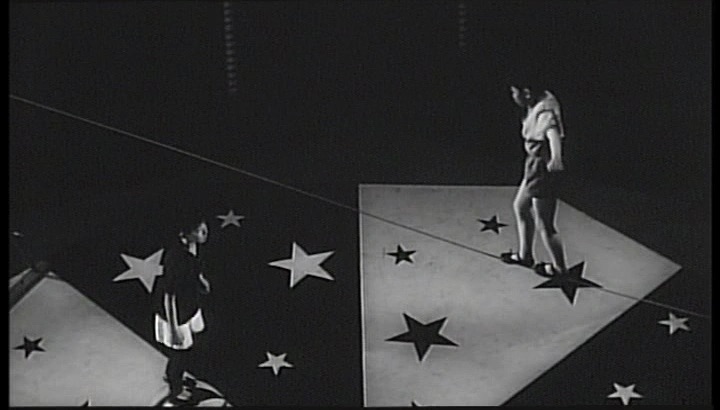

Part family saga, part transcendental journey, Circus Boys tracks the passage of two orphaned brothers, Jinta (the older one) and Wataru, who are adopted by a circus family when they are young. They quickly realize the importance of developing a specialty act if they want to stay with the troupe so they focus on becoming acrobats. One night while learning to walk the tightrope, Wataru is frightened by a clap of thunder and falls to the ground. Luckily, Jinta helps cushion his brother’s fall but injures his leg permanently in the event. As time passes, Wataru and Maria, another orphan who was adopted by the traveling carnival, become Japan’s first child trapeze artists. But Jinta, lacking a marketable skill for the big top, decides to set out to find his own place in the world.

Relying on his gift of gab and enterprising nature, Jinta reinvents himself as a traveling con artist, assuming new identities for each phony product he pitches to potential customers along the way. His hustler schemes prove profitable, from selling coal that “burns for an entire month” to cure-all medicines and miraculous soap products. Unfortunately, his lucky streak ends when he encroaches on a yakuza-ruled province and is threatened with death by the gangsters. Yoshimoto (Yoshio Harada), the mob boss, ends up being impressed by Jinta’s bravery when faced with decapitation and the young drifter is inducted into their clan. Jinta quickly continues his career as a flim-flam artist with yakuza backing but when he falls in love with Plaything (Moe Kamura), the unhappy mistress of a sexually insatiable chieftain named Samejima (Bunshi Katsura), he risks losing everything that matters.

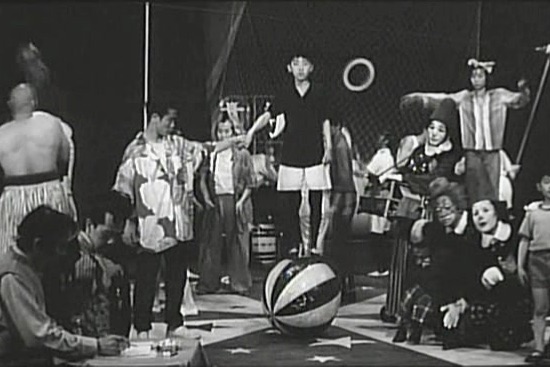

Meanwhile, Wataru has his own problems with the circus troupe. At the premiere of his “Dynamic New Cycle Bowl Show,” Hanako the elephant panics, crushing his handler and causing the audience to panic and flee. The circus folds soon after that tragedy leaving only Wataru, Maria and a few employees to face an uncertain future. They eventually decide to create a new big top attraction that they hope will restore their reputation and prove profitable. The daring stunt involves Wataru and Maria racing bicycles at high speed around the walls of a steel cage in a gravity-defying manner. But is it too dangerous to perform and is it guaranteed to restore the circus to their former glory?

The parallel journeys of Jinta and Wataru through the ups and downs of their lives provide a fascinating narrative arc for Circus Boys. Even though the two brothers are never reunited after parting ways, they maintain an almost psychic connection to each other through their nighttime observance of star patterns and celestial signs.

The entire movie has a dreamlike quality, enhanced by the gorgeous monochromatic cinematography of Yuichi Nagata. The consistently stunning black and white imagery pays homage (whether intentional or not) to silent cinema classics such as the 1924 circus melodrama He Who Gets Slapped with Lon Chaney as well as the carnival-like ambiance of Fellini movies like Variety Lights (1950) and the finale to his 8 ½ (1963).

Director Hayashi obviously has a genuine nostalgia for the golden age of circuses but his visual approach to that milieu is fantasy mixed with period recreations. For example, Hanako the elephant is not a real animal and his entire body is never seen in wide shots. Instead, only a detail of his face or head or part of his torso is glimpsed and it is either an animatronic device or someone manipulating a rubber and latex creation (The elephant was also glimpsed in Hayashi’s first film To Sleep So As to Dream and Zipang (1990), the director’s follow-up to Circus Boys). Also, some of the more ambitious and death-defying stunts are shown in partial detail but capture the essence of the act through atmospheric lighting, sound effects and circus themed music.

Although a specific time period is never identified during the course of Circus Boys, the events are clearly taking place around the turn of the century as we notice the arrival of a new midway attraction in one scene, which announces an amazing new technology, “moving pictures.” Even when both storylines threaten to end in tragedy, Hayashi maintains a sense of wonder and delight throughout his evocative visual canvas. Jinta’s story, in fact, seems to transcend reality at its climax, as Jinta and Plaything prepare to enter another dimension or is it a mirage? Viewers will have their own interpretations of this but Circus Boys is a refreshingly different approach to a familiar cinematic genre, one that is sad and joyful, magical and mystical.

Kaizo Hayashi is one of the more exciting and innovative talents of his generation to emerge in the early to mid-1980s as the new Japanese cinema was taking shape with such striking directors as Shinya Tsukamoto (Tetsuo: The Iron Man [1989], Tokyo Fist [1995) and Sogo Ishii (Crazy Thunder Road [1980], Crazy Family [1984] paving the way. Hayashi’s work was unique because it looked back at Japan’s past via his celebration and usage of silent film techniques but it also looked forward with its postmodern approach to film genres.

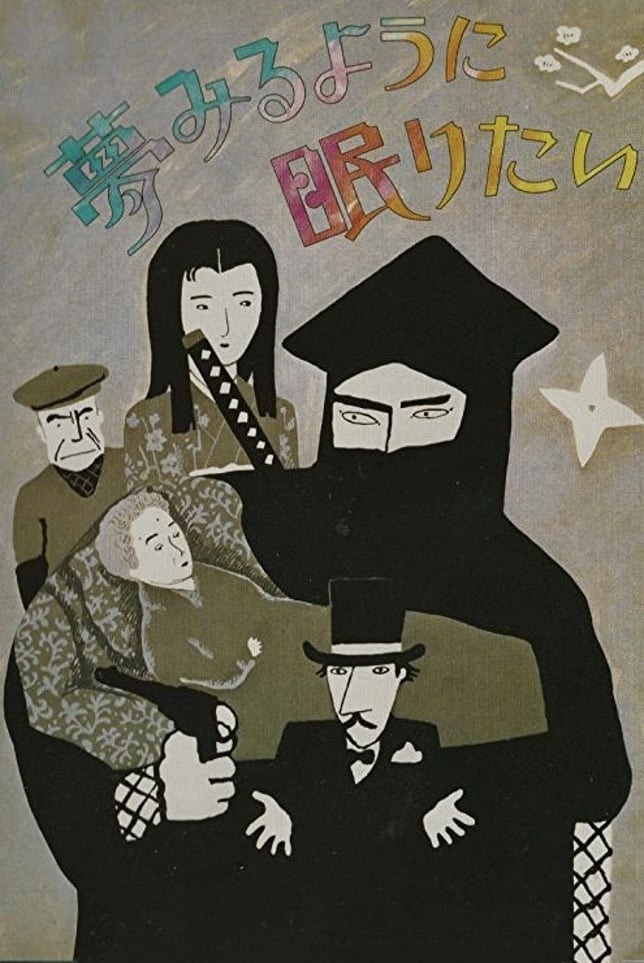

To Sleep So As to Dream (1986), Hayashi’s critically acclaimed debut feature, was a playful noir with no dialogue (just sound effects) that followed the search by two down-on-their-luck detectives for the missing daughter of a former movie star. Similar to the early work of Canadian auteur Guy Madden, Hayashi’s film was called “a stylish homage to the silent screen grounded in the early days of Japan’s own cinematic history” (by authors Tom Mes and Jasper Sharp in The Midnight Eye Guide to New Japanese Film).

Circus Boys, Hayashi’s sophomore effort, was equally well received and continued the director’s nostalgic black and white homage to cinema’s past. Mes and Sharp noted that “By such simple lighting techniques as a selective use of spotlights and masking of parts of the screen in a misty haze, he [Hayashi] gives the suggestion of a far bigger world outside of the one in which the film actually plays.” He also mixed film industry veterans with up-and-coming actors in his cast such as Yoshio Harada (in the role of Jinta’s yakuza boss) from Seijun Suzuki’s A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness (1977) and Hideo Gosha’s Hunter in the Dark (1979). Jian Xiu (Tokyo Skin, 1996) plays the young adult version of Watura with Hiroshi Mikami (A Watcher in the Attic, 1993) as Jinta in the post-circus years.

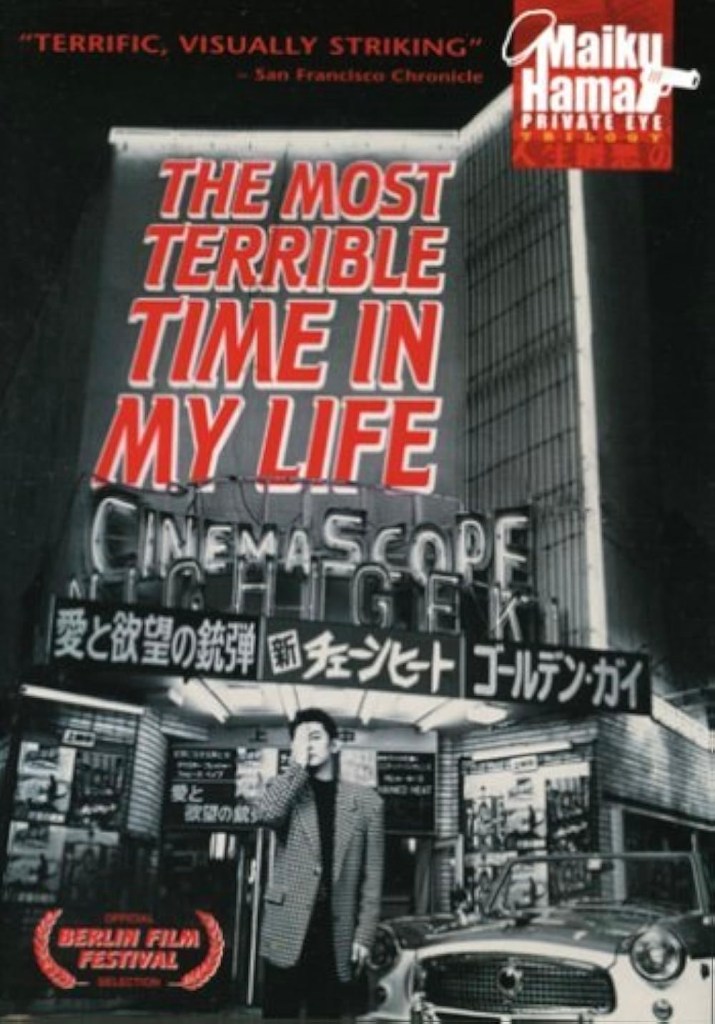

Hayashi’s true breakout film, however, and the one that made him an important figure in the new wave of Japanese filmmakers was The Most Terrible Time in My Life (1993), a stylish tribute to 60s crime thrillers starring Masatoshi Nagase as a private detective in Yokohoma named Maiku Hama (a homage to Mickey Spillane’s tough guy hero Mike Hammer). Edward Guthmann of the San Francisco Chronicle called it “a terrific, visually striking Japanese import…Filmed in black-and-white and set in a section of Yokohama that evokes the ’60s, “The Most Terrible Time” also recalls Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” and other gems of the French new wave.” It was the first in a trilogy of detective thrillers with Nagase as private eye Hama and the other two were The Stairway to a Distant Past (1995) and The Trap aka Wana (1996).

Still, Circus Boys is a great entry point for Hayashi’s work but it is not currently available on Blu-Ray or DVD in the U.S. However, you can stream a decent copy of it with English subtitles on the Cave of Forgotten Films website.

Other links of interest:

https://japansociety.org/film/so-as-to-dream-eternal-mysteries-of-kaizo-hayashi/