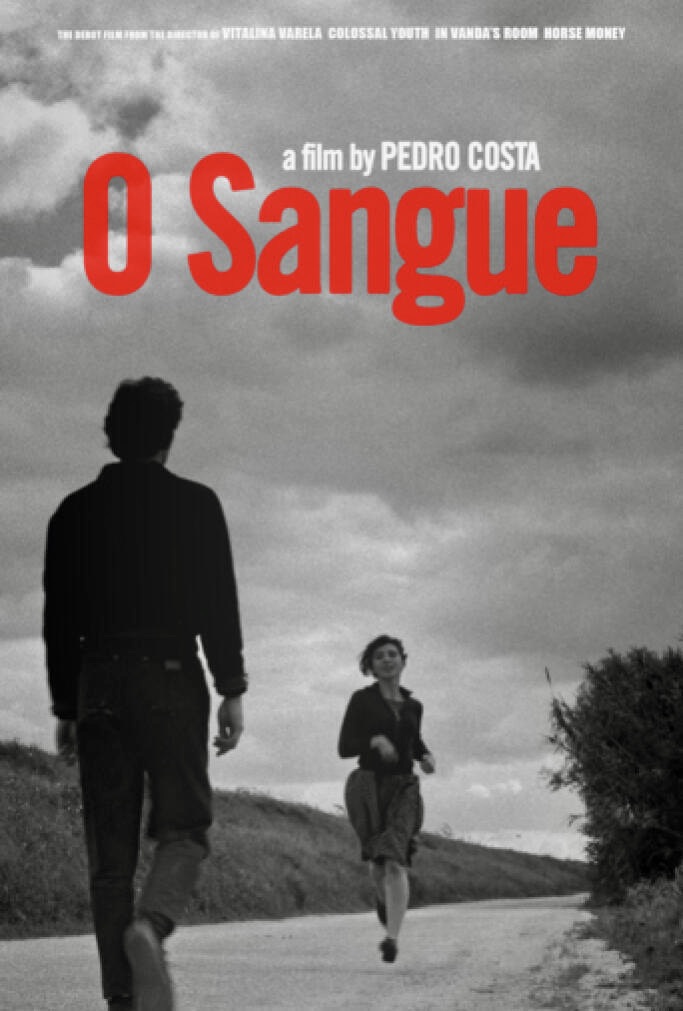

Most film aficionados known that the Cinema Novo movement of the 1960s in Brazil was influenced by both Neorealism and New Wave filmmakers but became an identifiable style of its own. Portugal also had their own Cinema Novo movement in the sixties but it transitioned into a different aesthetic approach in the 1980s known as “The School of Reis,” named after Antonio Reis, a filmmaker and professor at the Lisbon Theater and Film School. Reis influenced a new generation of filmmakers that includes Manuela Viegas, Joaquim Sapinho, Joao Pedro Rodgrigues and Pedro Costa to name a few. Among this group Costa is probably the best known in the U.S. due to his work being exhibited at film festivals and art houses as well as a trilogy of his films known as Letters from Fontainhas being distributed on DVD and Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection. Less known is his 1989 debut feature, O Sangre aka Blood, which Michelle Carey of Senses of Cinema called, “Undoubtedly one of the most remarkable film debuts of the last 20 years.”

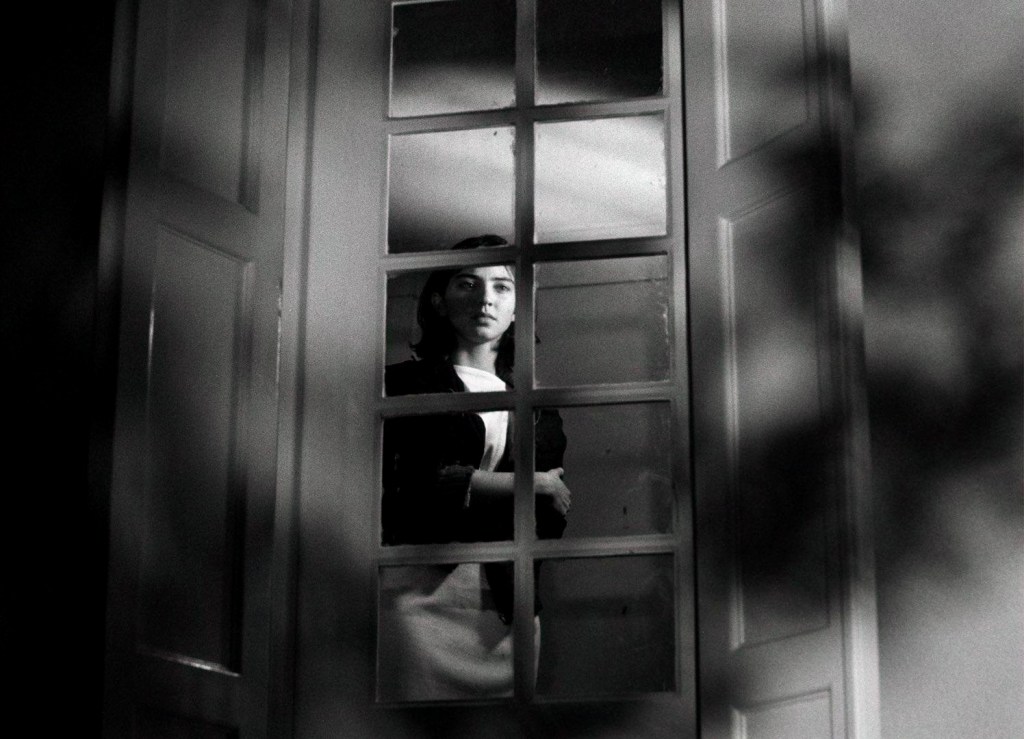

Visually dazzling and mysterious in form, O Sangre dispenses with traditional narrative devices and serves up a series of intense encounters between the featured players, requiring the viewer to fill in the missing gaps in their timeline, backstory and relationships. Even then, there are unanswered questions which may never yield an answer but there is a hypnotic allure to the imagery that eventually rewards the viewer’s curiosity with a new way to explore identity and human intimacy in visual terms. It is certainly experimental in its approach but not inaccessible. And adventurous filmgoers might enjoy it as not only a passionate cinephile homage to some of the great films and directors in cinema history but as a puzzle to contemplate and unravel.

The three characters at the core of O Sangre are the seventeen year old Vicente (Pedro Hestnes), his ten year old brother Nino (Nuno Ferreira) and Clara (Ines de Medeiros), a close friend who is like an unofficial member of their family. The two brothers live in abject poverty with their often absent father (Canto e Castro), who is suffering from a terminal illness. Their circumstances change when the father goes missing. Did he die from his illness, commit suicide or was he murdered? The mystery is compounded by a scene where we see Vicente and Clara dragging something heavy in a sleeping bag and dumping it into an open grave.

A Film Noir-like ambiance envelopes the entire movie and Vicente is soon being stalked by two ominous creditors who demand payment for the money Vicente’s missing father owns them. The brothers’ uncle (Luis Miguel Cintra) and his mistress (Ana Otero) also show up inquiring about the missing father and insistent on adopting Nino, who has no interest in leaving Vicente. Adding an additional layer of intrigue is the discovery of the missing father’s mistress (Isabel de Castro).

We never really learn what happened to Vicente and Nino’s mother and the dynamic between the two brothers begins to change after they are separated by the uncle. Clara tries to help them both and acts as a maternal figure for Nino while her relationship with Vicente alternates between being a confidante and a potential lover.

All of this, of course, is just my subjective take on the characters depicted in O Sangre but the ravishing black and white cinematography by Acacio de Almeida, Elso Roque and Martin Schafter transforms the film into q brooding mood piece that is lyrical, haunting and dreamlike.

Some critics found O Sangre to be a thesis film on steroids where Costa was trying to impress everyone with his vast cinematic knowledge of past masters who have influenced him. Yes, you can see allusions or references to Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959), Luis Bunuel’s Los Olvidados (1950), Nicholas Ray’s They Live by Night (1948), F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927), Robert Bresson’s Mouchette (1967) and many more like Val Lewton’s I Walked with a Zombie, which Costa would re-imagine as his next feature, Casa de Lava aka Down to Earth (1994).

I also see films like Bela Tarr’s Damnation (1988) and Leos Carax’s Boy Meets Girl (1984) as visual counterparts to O Sangre, whether they are intentional or not, but that doesn’t mean Costa’s film is not an original work of art. Ironically, Costa would abandon this approach for his future films, preferring a more stripped-down, minimalistic visual aesthetic. He would also move away from using professional actors, hiring non-professionals to play versions of themselves in a unique fusion of documentary and fiction, which first appeared in Ossos aka Bones (1997), the first film in his Fountainhas trilogy. The other two movies in the triptych are No Quarto da Vanda (In Vanda’s Room, 2000) and Juventude em Marcha (Colossal Youth, 2006), both of which deal with some residents in the slums of Lisbon who would soon be displaced after the city’s urban renewal reforms.

Costa would later say in a 2006 interview, that “O Sangre was also the beginning of my love—maybe love is the wrong word—for domestic cinema. A kind of cinema that shows how people live.” As for his evolving brand of filmmaking which favors image and sound over a discernible plot, the filmmaker stated in a conversation with Ionut Mares for Films in Frame: “The first thing that cinema should do is not propaganda or talk about something or tell a story. The first thing cinema should do, and it’s good at this, it’s to be an instrument to make you see and hear things that normally you don’t see or hear. To make you pay more attention to some parts of reality in a city or in a faraway country…I would even say that normally the first thing you see if the film is serious it’s probably something that is not quite right, because the world it’s not right, it’s not perfect. Usually what you see in a film or what you should see is that things could be better. I think that it’s one of the tasks or functions of all great films and filmmakers.”

The opening scene in O Sangre reflects this. It opens with a black screen and the sound of people talking. We then see Vicente standing in the middle of a road and can hear someone berating him. Suddenly a hand enters the frame and slaps Vincente across the face before we get the reverse angle revealing the angry father, who then turns and walks into the distance down the road. It is an almost shocking moment that immediately draws you into the film and compels you to make sense of who and what you are seeing. O Sangre is full of bravura moments like this and one of the most memorable scenes takes place at a nighttime village festival. Vicente gets into a physical altercation with a boyfriend of Clara’s and chases him into a cloud of smoke in the background as Clara trails behind and dancers at an open air café waltz on the left side of the frame.

Equally important to the dreamlike mood of O Sangre is the sound design by Pedro Caldas – half-heard conversations, dogs barking, babies crying, etc. – and Costa’s eclectic choice of music. Costa weaves in and out of the dark, moody orchestral music by Antonio Pinho Vargas and slips in music cues from diverse sources to underscore certain scenes – everything from Igor Stravinsky’s The Firebird to melodies sung by Manuel Joao Vieira (in the minor role of Zeca) to “This is the Day” by Brit pop band The The (played under a magical carnival scene with Vicente and Clara).

It has taken more than 36 years for O Sangre to emerge from obscurity to finally achieve recognition as the groundbreaking debut of possibly Portugal’s greatest living filmmaker. It seems just as fresh and as timeless today as when it was first released, even though Costa has long abandoned the more formal techniques he once employed here. A writer for the Strictly Film School website notes that Costa’s debut feature “bears the characteristic imprint of what would prove to be his familiar preoccupations: absent parents, surrogate families, unreconciled ghosts, the trauma and violence of displacement, the ache (and isolation) of longing.”

Among the many admirers of O Sangre is Australian film critic Adrian Martin, who wrote an essay on the movie: “From the very first moments of his first feature Blood, Pedro Costa forces us to see something new and singular in cinema, rather than something generic and familiar. The black-and-white cinematography … pushes far beyond a fashionable effect of high contrast, and into something visionary: whites that burn, blacks that devour. Immediately, faces are disfigured, bodies deformed by this richly oneiric work on light, darkness, shadow and staging.”

Equally impressed is The New York Times and RogerEbert.com contributor Glenn Kenny who wrote on the MUBI blog: “It is a breathtaking film to watch. An incredibly vibrant first feature that has its own vital blood pulsing through its celluloid veins….The portrait the picture paints of a criminal underworld that’s just as out of sorts and desultory as the brothers themselves is droll, understated, signaling a filmmaker of admirable maturity and humor.”

In September 2009 the UK outfit Second Run Films released O Sangre on DVD featuring a new HD transfer approved by the director and including a booklet featuring the aforementioned Adrian Martin essay and other extras. It is now out of print but Grasshopper Films picked up O Sangre for theatrical distribution in the U.S. so it is quite possible the movie may get a new life on Blu-ray in the future. Meanwhile, you might be able to find a better than average copy of the film streaming (with English subtitles) on Youtube, which is where I first discovered it.

Other links of interest:

https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2009/sep/17/pedro-costa-tate-retrospective

https://theeveningclass.blogspot.com/2008/03/pedro-costa-and-others-on-o-sangue.html

https://www.filmsinframe.com/en/interviews/pedro-costa-interview